Familiar with the distinct drum of woodpeckers? Florida is home to eight species of woodpeckers — and the now extinct ivory-billed woodpecker — so chances are they are in your area. But how much do you know about your wood-pecking pals?

Read on to find out what makes a woodpecker a woodpecker. Or head over to YouTube for an in-depth look into woodpecker adaptations, identification, and conservation in our Wild Sarasota Webinar: Woodpeckers of Florida.

What’s a Woodpecker?

Simply put, a woodpecker is a member of the Picidae family. In Florida, this includes the red-bellied woodpecker, red-headed woodpecker, pileated woodpecker, red-cockaded woodpecker, downy woodpecker, hairy woodpecker, yellow-bellied sapsucker, and yellow-shafted northern flicker. If you’re interested in identifying your neighborhood woodpecker, visit our Watch out for woodpeckers: identifying Sarasota species blog.

Woodpeckers are omnivorous, cavity nesters with a distinctive, swooping flight pattern. Though beak shape and size varies by species, all woodpeckers have a chisel-like bill. This allows them to carve out these cavities in a process known as excavating. The other instances in which woodpeckers will peck are when removing bark to look for food or to communicate. Drumming is the name given the act of woodpeckers pecking on pretty much any resonant surface (including your windows or gutters) to communicate and often to attract a mate.

But how do woodpeckers get in position to peck and sustain all that force?

Tree-climbing Tricks

While there are differences between species and individuals, woodpeckers are characteristically known to perch on the trunks of trees moving vertically rather than resting on horizontal branches like most birds. But how do they manage to cling to the side of trees?

Zygodactyl Feet and Curved Talons

Woodpecker toes are arranged in a formation known as zygodactyl with the second and third toe facing forward and the other two point backward. This pairing creates an “X” or “K” shape that aids in gripping tree-trunks. Raptors (birds of prey) like eagles, owls, osprey, and hawks also have zygodactyl feet which assists them to grasp their prey. Coupled with this special toe arrangement, woodpeckers have curved talons. This allows them to dig into the tree at a 90-degree angle giving them extra grip.

Bracing Tail Feathers

Once on the tree, woodpeckers also have special tail feathers that act as a kick-stand. These tail feathers are extra stiff – fortified with black pigment – and curved at the end to help prop them up.

Tongue-tied: Hyolingual Apparatus

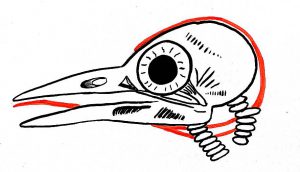

Arguably the coolest adaptation of woodpeckers is their hyolingual apparatus, commonly known as a tongue. At a length of over 10 inches, woodpecker tongues actually wrap around the skull splitting into two seperate muscles and then connecting back into the right eye-socket. Woodpeckers deploy their tongues in a raking motion, removing the contents from the cavity they have just drilled. The end of the tongue, known as the paraglossal, can either be barbed or brush-like to help collect grubs and other good eating from their holes.

The wrapping of the hyolingual apparatus around the skull and contraction when pecking is one measure of brain defense. It helps to secure the head from jostling around too much, but a lot more goes into keeping woodpeckers concussion-free.

Concussion Defense

Woodpeckers peck with a force of about 1000G — that’s ten times the impact withstood when NFL players collide. Moreover, woodpeckers may drum on wood at a speed of 20 pecks per second. So are woodpeckers flying around perpetually concussed?

While woodpeckers do have a characteristic, undulating flight pattern, it’s not from brain trauma. Woodpeckers are specially adapted to sustain this force with certain features to keep their brain in place.

Small brain and porous skull

Woodpeckers have particularly small brains lowering the weight:surface area ratio. They’re also encased in a strong skull that can withstand a lot of force with many pores that help absorb energy.

Little cerebrospinal fluid

The human brain sits in a large bath of cerebrospinal fluid within the skull. Woodpeckers have a lot less fluid between the brain and skull decreasing mobility and rattling of the brain. This limited movement means less momentum and force to be exerted on the brain.

Neck muscles and cartilage

Another measure to protect against concussions is securing the neck to help protect against whiplash. Muscles extend down from the skull along the spine to stabilize the head and woodpeckers have extra cartilage to soften the blows.

Longer lower beak

Woodpeckers’ lower beak extends further than the upper part. This diverts the flow of energy from the head into its chest and body which can sustain more force than the head.

Read all our Wild Sarasota blogs HERE

This is just a taste of all the wild, wacky, and wily adaptations of woodpeckers so be sure to watch our Wild Sarasota webinar: Woodpecker of Florida on YouTube to learn more!

0

0