As an Extension agent, I give a lot of presentations about elasmobranchs. Sharks and rays, that is.

There are many reasons why, but one of the main reasons is that people are eager to learn more about these fascinating creatures. So, in addition to my presentations, I decided to start “Shark Bits,” a series of blog posts highlighting cool facts about sharks and rays. Of course, if you have a question, you can submit your shark question any time using this form, and I will answer it in a blog post.

Thank you, and I hope you enjoy the first edition of “Shark Bits.”

Shark Reproduction

The earliest shark fossil record dates back to the early Devonian Period, around 410 million years ago. That is about 200 million years before the earliest dinosaurs walked the earth. Since then, sharks have been through many evolutionary adaptations, which have helped them become some of the most successful fishes in the ocean. Among those remarkable adaptations that have contributed to their survival and evolutionary success are their reproductive adaptations. One of these prodigious adaptations is internal fertilization.

Fertilization is the union of a sperm nucleus, of paternal origin, with an egg nucleus, of maternal origin, to form the primary nucleus of an embryo. In other words, fertilization is the process of fertilizing an egg produced by a female animal or plant, involving the fusion of male and female gametes to give rise to a new individual organism.

The vast majority of bony fishes, such as groupers, snappers, and snook, rely on external fertilization. That means that sperm and eggs are released into the external environment, and fertilization does not occur inside the female. One big disadvantage of external fertilization is that a large number of gametes (eggs and sperm) are wasted and left unfertilized. Also, the chances of fertilization are reduced by environmental factors and predators, to the point that eggs and sperm might never come into contact.

All elasmobranchs—cartilaginous fishes, including all sharks and rays—developed internal fertilization, which occurs inside the female reproductive tract. One of the main advantages of this advanced reproductive adaptation is that the fertilized egg is protected from predators and harsh environments, increasing the survival of the fertilized egg.

CLASPERS

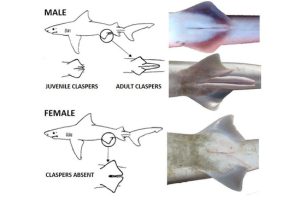

For internal fertilization to occur, though, a mechanism for injecting the sperm into the female reproductive system must exist. Sharks and rays have developed copulatory organs, known as claspers. These intromittent organs (or, specialized external organs) are elongated modifications of the pelvic fins.

Claspers are present in all male sharks and rays, and absent in all female sharks and rays. Therefore, by looking at the ventral region of a shark or a ray—in other words, its underside—you can tell if you are viewing a female or male shark.

The use of claspers in elasmobranchs influences their reproductive success. And, the retention of fertilized eggs by females opens the door for other advanced reproductive strategies displayed by some elasmobranchs. One such strategy is viviparity, or the retention and growth of the fertilized egg within the maternal body until the newborn is capable of independent existence.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post, and are ready for more “Shark Bits.” At the least, now you know how to tell a female shark from a male shark, which might help to impress your friends next time you visit your local aquarium or go on your next diving trip.

Featured image by Nautilus Creative – stock.adobe.com

7

7