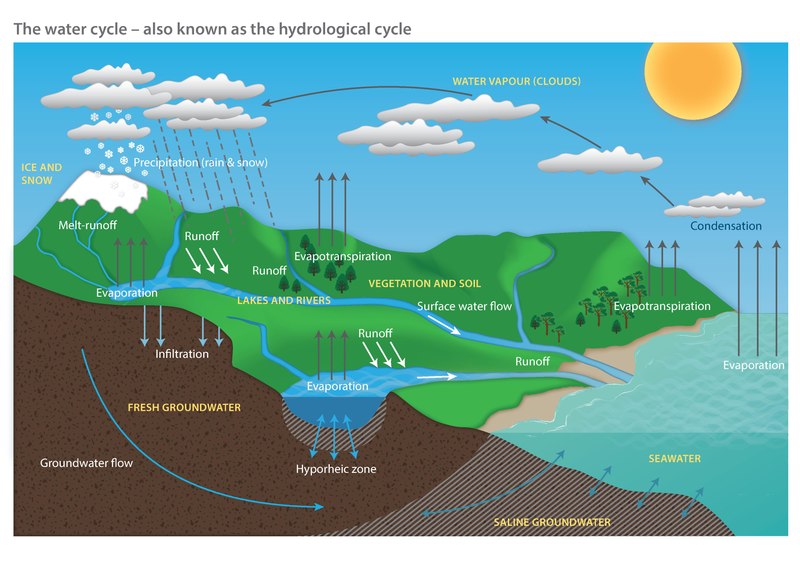

We have all seen or learned the water cycle at some point in our lives, whether we were paying attention or not. Perhaps you sang a song to remember all the terms or drew the cycle of water as a kid. I’m sure you remember some or all these terms:

How we learn the water cycle…

I’d be willing to bet that the water cycle you learned came with mountains in the background, snow falling to the ground and few buildings in the picture. Unfortunately, for those of us in Florida, and especially the Tampa Bay area, this is far from reality. We lack mountains, we lack snow and we certainly do not lack buildings. All of these elements play a significant role in the water cycle, but I want to focus on what we do have, which is buildings.

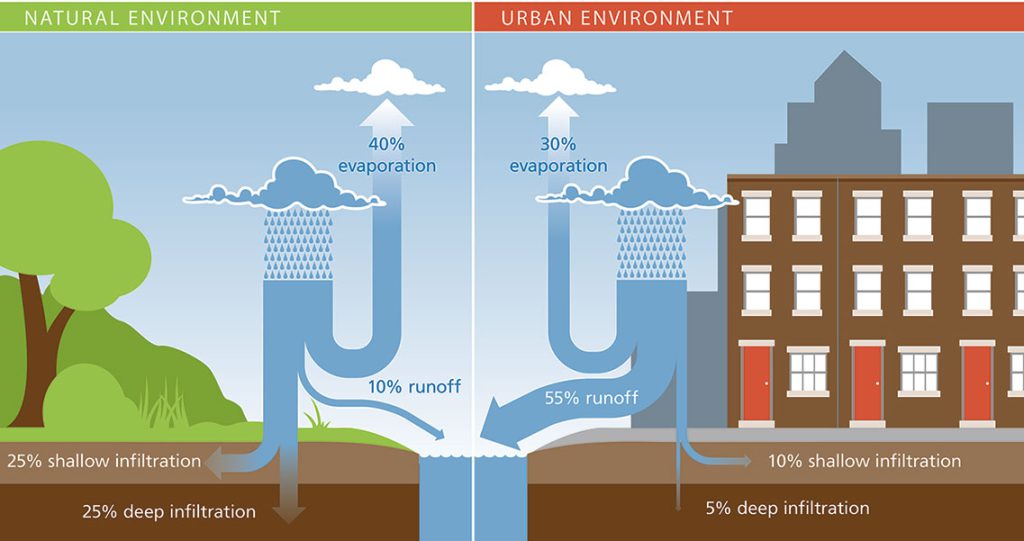

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency produced a publication that looks at how the water cycle functions in a natural area, like where I’m stationed at Brooker Creek Preserve versus a more developed area, like, well, most of Tampa Bay. While the water cycle in both settings still includes the main terms highlighted above, they function significantly differently.

When rain falls in a natural area, tree leaves intercept water droplets, slowing their velocity before hitting the ground. Once the rain reaches the ground, water navigates slowly through an expanse of soil or leaf litter. With enough time, the water will either evaporate or go down into the soil.

How we should learn the water cycle…

When rain falls in an urban area, the water droplets reach hard surfaces (roofs, parking lots, sidewalks, roadways) often at full velocity. Once the rain reaches the ground, if it doesn’t evaporate from the extreme heat of urban settings – this is what’s known as the “urban heat island effect — it has no choice but to flow by gravity along these hard surfaces. As Extension faculty, we sometimes call hard surfaces “impervious.” All of this rainwater collects and flows at a fast rate along these hot, dirty, hard surfaces, which can result in warmer, sediment-filled, polluted waters. So, in this situation we have a lot more runoff compared to the natural area because the water has nowhere to infiltrate.

Where does all this warm, turbulent, polluted water end up?

Depending on where you live, the water will either flow through a storm drain along sidewalks and roads to a nearby stormwater pond or other body of water. But some areas lack storm drains, and the water would flow to a water body. In either situation, there is no formal treatment of the water before its final destination.

What can we do to help? We need to do what we can in our yards to encourage and invite rainwater to stay. As my colleague says, “Don’t let your runoff runoff.” Any plants you install in your yard can help with this, preventing soil erosion and encouraging infiltration filtration of pollutants. You can also consider installing a rain garden if water collects in areas of your yard. If you’re in Pinellas County, consider joining the Adopt-A-Drain program.

We can all do our part on our property to help protect water quality.

2

2