The University of Florida has announced that a new dormitory for graduate students and visiting scholars at the UF/IFAS Tropical Research and Education Center (TREC) in Homestead, Florida, will be named in honor of UF professor emerita and alumna Pauline O. Lawrence.

The naming is one of several firsts for Lawrence and the university. As a graduate student at UF in the 1960s and 1970s, Lawrence was the first Black female student in entomology and the first female student to live and study on the UF/IFAS TREC campus. The Pauline O. Lawrence Student Residence will be the first UF building named after a Black person.

“This was a big surprise, and I am deeply honored,” Lawrence said. She and her husband Carlton Davis, distinguished professor emeritus in the UF/IFAS food and resource economics department, have strongly supported the campaign to build the dorm, but she never asked or expected to see her name on it, she said.

“I hope it reminds all the future graduate students coming through the center that entomology and other scientific disciplines are open to everyone, regardless of background,” Lawrence said.

“The dorms are part of a larger vision for TREC in which graduate students are an integral part of the research and teaching community at the center,” said Edward ‘Gilly’ Evans, the center’s director.

“Graduate students are an essential part of what we do at research and education centers. At TREC, they play a critical role in our research supporting agriculture and natural resources in South Florida, all while receiving mentorship and professional development from our faculty,” Evans explained.

However, working and learning at a research and education center comes with challenges, not least of which is finding a place nearby to live.

“Our graduate students often have a difficult time finding housing, especially now that Miami-Dade has been cited as the most expensive housing market in the U.S. Providing affordable, quality living space for our graduate students right on our campus will help us attract the best and brightest. We are extremely grateful to all those who have contributed to this effort and made it a reality,” Evans said, noting that many have contributed to the fund to build the dorms through the center’s annual event, One Night in the Tropics.

“Naming memorializes the contributions of faculty, students, donors — and Dr. Lawrence is all three — who have helped build the foundation for excellence at UF,” said J. Scott Angle, UF’s senior vice president for agriculture and natural resources and leader of UF/IFAS. “This moment in our university’s history reminds us that we strive for preeminence by making our institution more inclusive, diverse, equitable and accessible for all people. Dr. Lawrence’s career is an inspiration for us to undertake this important work.”

The project is now in the design phase with construction planned for 2023.

A career inspired by curiosity, mentorship

Lawrence grew up in Jamaica and was surrounded by agriculture. Her family ran a farm with dairy cows, bananas and spices in a nearby village, and her father grew fruit trees and vegetables next to the family’s house. As a child, Lawrence would sneak bites of tomatoes still on the vine and then attribute the damage to insects when her father asked what had happened.

“My dad saw right through me!” Lawrence recalled with a laugh. As punishment, he tasked her with collecting all the different insects she could find in the garden. That experience would grow into a lifelong fascination with insects and agricultural pests.

As an undergraduate at the University of the West Indies, Lawrence studied zoology and wrote her honors thesis on swallowtail butterflies and their caterpillars, which are citrus pests. After graduation, she worked for the Jamaican Ministry of Agriculture, where she became interested in fruit fly pests, which cause significant economic damage to tropical fruits in Jamaica, Florida and throughout the Caribbean. Lawrence then received a scholarship from the government of Jamaica to attend UF as a master’s student in entomology.

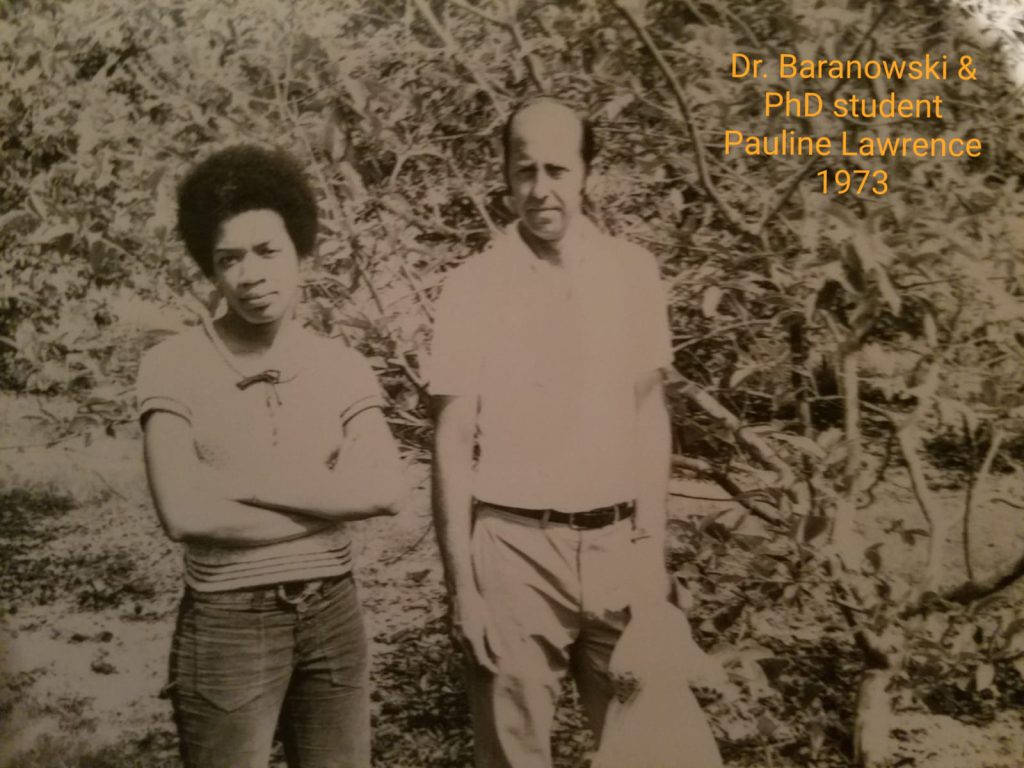

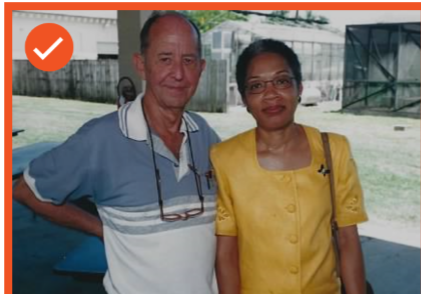

Upon completion of her master’s, she was awarded a research assistantship to pursue a Ph.D. by professor Richard Baranowski, an international expert on tephritid fruit flies at TREC. She conducted her field research at TREC under professor Baranowski’s guidance and completed the remainder of her degree work in Gainesville on the UF main campus and at the US Department of Agriculture Laboratory.

When she arrived in Homestead in the early 1970s, she was welcomed by Baranowski, his wife and daughters.

“Dr. Baranowski’s mentorship and generosity had a lasting impact. He saw me as a whole person and encouraged me to pursue the work I wanted to do and gave me the freedom to explore the questions I had.” Lawrence said.

Lawrence would go on to make discoveries in the area of beneficial insect physiology and development, with a focus on parasitic wasps. She discovered the first symbiotic virus that lives within a wasp used to control tephritid fruit flies. The virus is essential in helping the wasp to kill fly maggots within the fruit. As a result, this wasp is one of the most effective biological control agents used against tephritid fruit flies worldwide. Further, Lawrence’s findings revealed the importance of understanding the developmental physiology of beneficials prior to their incorporation into biological control programs.

Lawrence and her collaborators were the first to sequence the viral genes through the continuous support of competitive grants from the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the US Department of Agriculture.

Lawrence’s discoveries and associated research were recognized with an NSF 1988 Career Advancement Award for Women. She was also named the 1999 Pioneer Lecturer Honoree by the Florida Entomological Society as a result of her unique discoveries.

Learn more about Lawrence’s career and accomplishments in her UF/IFAS Women Trailblazers profile.

While at TREC, Lawrence lived mainly by herself in a big house tucked behind the main buildings. At the time, TREC rarely hosted graduate students, so the house served as an ad hoc residence.

Lawrence later learned that Baranowski felt that it would be safer for her, a young Black woman and foreigner, to live on university property rather than in a small Southern town.

At one point, Lawrence shared the house with another graduate student and his family, and Baranowski successfully advocated for Lawrence’s mother to come and stay with her. Still, Lawrence recalls often feeling lonely and isolated on the 160-acre campus, then only accessible by backroads.

“Being by myself, it was difficult to focus on my studies at times, because of my fear of being so isolated,” Lawrence said.

Despite these challenges, Lawrence earned her doctorate and in 1976 became an assistant professor in the UF zoology department, achieved the rank of full professor in 1989 and moved to the UF/IFAS entomology and nematology department in 1994. As both a researcher and teacher, Lawrence was a founding member of UF’s Minority Mentor Program, now called the University Multicultural Mentor Program, and was committed to recruiting and mentoring minority undergraduate and graduate students and postdoctoral associates.

When she heard about director Evans’ vision of building a dorm at TREC, she thought back to her own experiences as a graduate student.

“I wish there had been a dorm when I was at TREC — not just a good, safe place to live, but a place that could build community among students,” she said. “I also really do believe in graduate students being exposed to working at research centers because they can meet people from all different disciplines and experience the cross-fertilization of ideas. I would encourage any graduate student to look for opportunities to work off main campus and broaden their horizons.”

8

8