Fungal and bacterial pathogens, as well as viruses and nematodes, can all affect the quality of seed potatoes. Infected seed can lower plant vigor and supply inoculum for further disease throughout the season. Late blight, Fusarium dry rot, scab, black dot, and bacterial soft rot are seed-borne diseases that are traditionally problematic. More recent concerns are with the disease, blackleg, caused by Dickeya dianthicola, an aggressive pathogen that has devastated potato crops in the mid-Atlantic region, and has been detected along the Easter seaboard including Florida on potato seed sourced from Maine and Canada. Potato growers throughout the US are on high alert wondering how to monitor for blackleg as well as other seed borne diseases.

Obtaining certified seed stock with a guaranteed low incidence of disease is the first step of a potato management program. Most seed producers in the U.S. have a seed certification program that provides a North American Certified Seed Potato Health Certificate to growers. Certification programs produce high-quality seed stock but nothing is guaranteed completely disease-free. The goal should be to minimize yield losses and pathogen spread by monitoring seed stock and avoiding planting symptomatic seed.

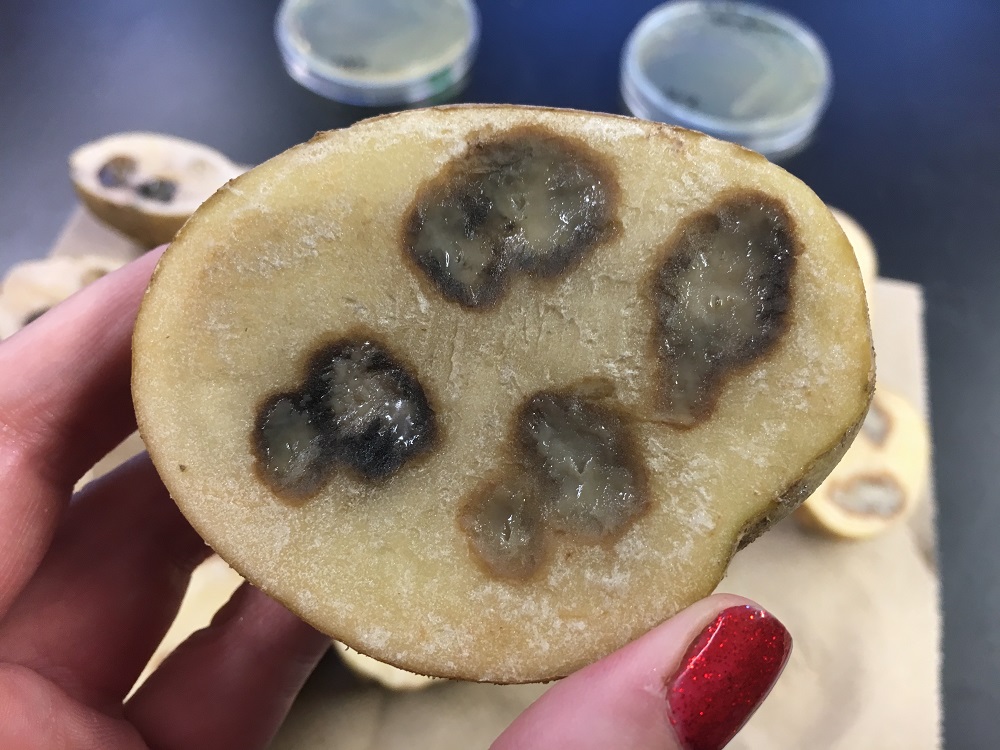

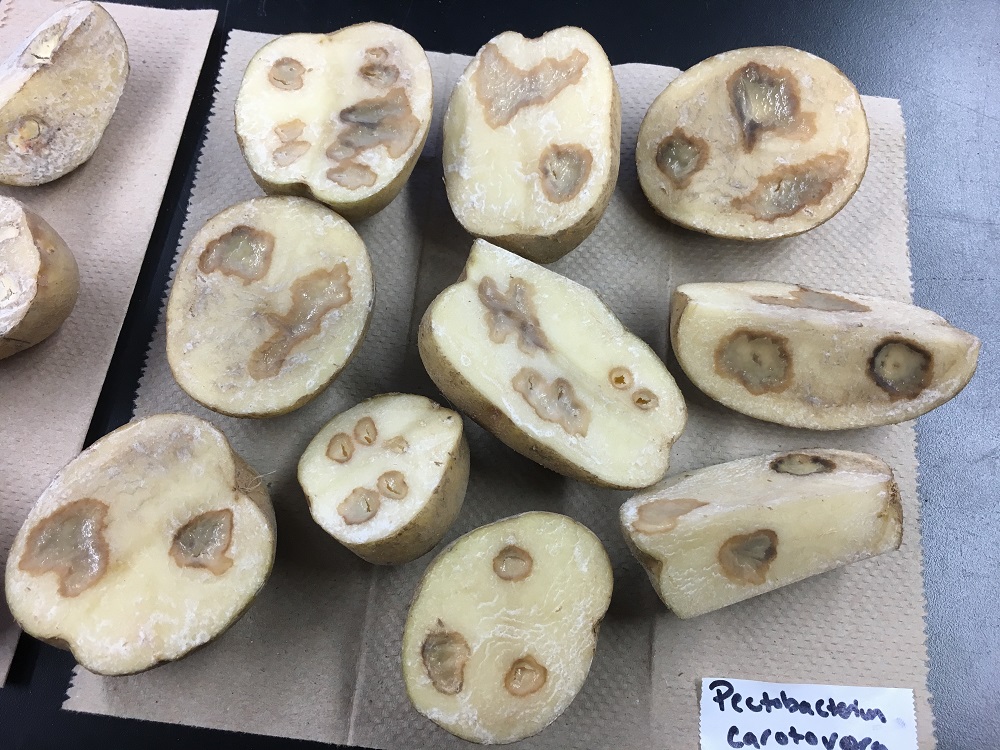

Certified seed stock shipments should be inspected and evaluated before accepting them. Visual inspections should be carried out carefully, examining the seed closely for both external and internal symptoms. External bruises, wounds and splits can indicate storage pathogen entry points. Seed should also be cut to inspect for internal symptoms, such as discoloration and rot, because sometimes these symptoms are not visible on the outside. Planting only certified seed is the first step to reducing seed-borne diseases, but other integrated pest management program methods, such as seed treatments, and In-season disease monitoring should also be considered to guarantee a productive potato crop.

0

0