“Whosoever comes into Italy, and from whence soever; but more especially if he come from suspected places, as Constantinople, never free from the plague; hee must bring to the Confines a certificate of his health, and in time of any plague, hee must bring the like to any City within land, where he is to passe, which certificates brought from place to place, and necessary to bee carried, they curiously observe and read. This paper is vulgarly called Bolletino della sanità; and if any man want it, he is shut up in the Lazareto, or Pest-house forty dayes, till it appeare he is healthfull, and this they call vulgarly far’ la quarantana. Neither will the Officers of health in any case dispence with him, but there hee shall have convenient lodging, and diet at his pleasure.”

– Fynes Moryson, commenting on his arrival in Italy in the spring of 1594

Health Passes – Older Than You Think

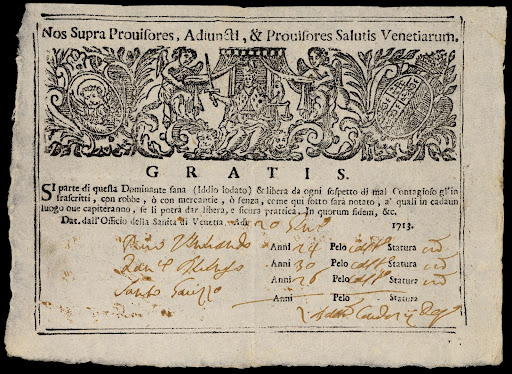

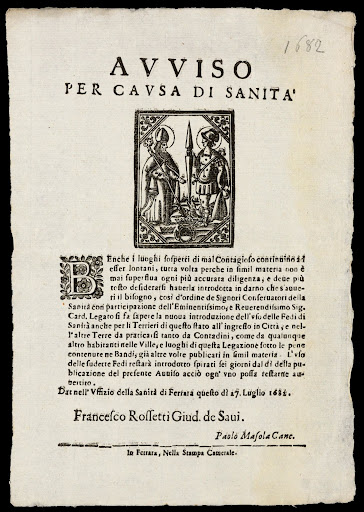

In early modern Europe, preventive health measures were issued during outbreaks to protect those who had not been infected yet. In 16th century Venice, for example, the “Fede di sanità” was the most common and effective document needed for anyone to enter the city via land. The “Fede di sanità”, one of the first examples of “health pass” (the earliest known dates to Milan in 1484), was an official document issued by the Health Office to attest that a named individual or group of people had travelled from a city which, at the time of their departure, was free of plague or contagious disease.

Those entering via sea were required instead to present the “Patente di sanità”, a similar document to the fedi. While the patenti are often beautiful prints with official seals and iconographic features which sought to enhance their authority, the fedi were usually pieces of handwritten paper filled out by a public health official.

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/rjrr3sra/images?id=xxdtfvbj

Visitors without a fede would not be allowed into cities of mainland Europe. The health pass system required the participation of multiple states in order for it to work. The development of the system involved the exercise of power on other states, as well as cooperation.

When large and powerful polities like Milan and Venice demanded a health pass as a condition of entry into a territory, smaller polities were inclined to produce health passes that could attest to departure from their towns and cities so that merchants passing through their cities and their own subjects could travel to major centres of trade.

A System of Trust

This system relied on a culture of mutual trust. Often during periods of infection, cities were perceived to be acting in a self-interested manner and the system of passes entered into difficulties. In 1576, for example, Venetian officials wrote to Padua and to each of the cities within the mainland that ‘it was with enormous displeasure’ that they had heard of individuals leaving Venice with the required fedi who were not being allowed to pass. This was described as a ‘terrible prejudice’ which was very damaging to the economy of the city.

The system of health passes was one of a number of measures adopted by the authorities in an attempt to prevent the spread of plague, and it worked in conjunction with other public health measures such as pesthouses, which were sites for the inspection and certification of imported goods like textiles as well as for the quarantine of travellers. Similarly, health passes were used to monitor the movement of merchandise and livestock as well as the movement of people.

In the past, health passes show that governments and states responded to the mobility of their populations by developing a shared European culture of public health measures. The European Union recently unveiled a “Digital Green Pass,” which shows a person’s vaccination status. It is recognized by all the nations in the bloc and has already eased travel between nations, allowing vaccine status to play a role in restrictions upon entry. As European nations look to national health passes, what can we learn from history?

By Dr. Sara Agnelli, One Health Adjunct Assistant Professor

Sources

Fynes Moryson, F. (1617). An Itinerary: Containing His Ten Years Travel Through the Twelve Dominions of Germany, Bohemia, Switzerland, Netherland, Denmark, Poland, Italy, Turkey, France, England, Scotland and Ireland. London: John Beale.

Crawshaw, J. L. S. (2012). Plague hospitals: public health for the city in early modern Venice . Ashgate.

Bamji, A. (2019). Health passes, print and public health in early modern Europe. Social History of Medicine, 32 (3). pp. 441-464.

0

0