Human Microbiome

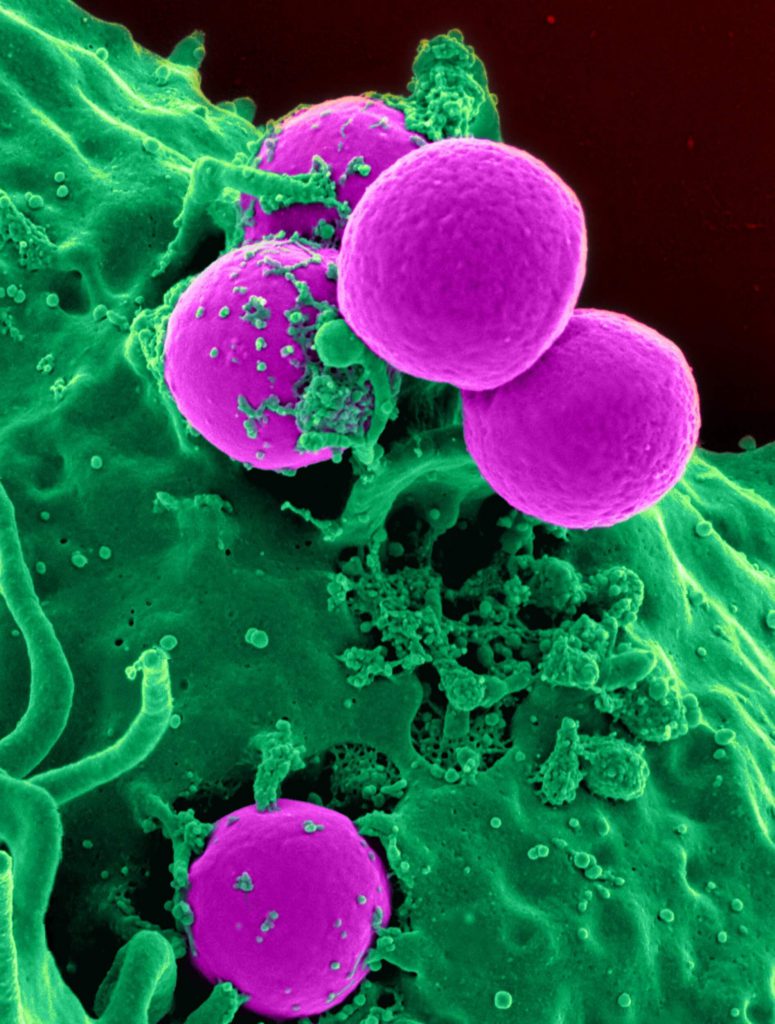

Every human being hosts around 10 trillion microorganisms in their gut, on their skin, in their hair. Consisting mostly of bacteria, they play several important roles and influence virtually every aspect of human life. For example, imbalances in the composition of the gut microbes are associated not only with obesity, type 1 diabetes, and inflammatory bowel diseases, but also with neurological and emotional issues, auto-immune disorders, and cognitive issues.

Every human being hosts around 10 trillion microorganisms in their gut, on their skin, in their hair. Consisting mostly of bacteria, they play several important roles and influence virtually every aspect of human life. For example, imbalances in the composition of the gut microbes are associated not only with obesity, type 1 diabetes, and inflammatory bowel diseases, but also with neurological and emotional issues, auto-immune disorders, and cognitive issues.

Individual choices for individual health

The importance of the microbiome for human health is common knowledge: just think of all the advertising for probiotics, yogurts with live ferments, fermented beverages (i.e. kombucha), and foods rich in natural fibers. Dietary choices are intuitively directly linked to the health of our microbiome, especially in our guts. Less obviously, other lifestyle choices affect our microbiomes: certain soaps and cleaning products may disrupt our skin microbiome, exercising and spending time outdoor helps strengthen our microbiomes, careful consumption of antibiotics and other medicines as well (i.e. often, when prescribing antibiotics, doctors prescribe probiotics as well to reinforce the gut microbiome).

Systemic factors for individual health

While most of the attention is directed to individual choices, there are many systemic factors that can affect people’s microbiomes. These are possibly more dangerous because they are more difficult to address requiring collective efforts to change cultural, social, and economic systems.

The main example is access to food. Even in the US, there are areas, described as food deserts, where it is impossible to purchase healthy and nutritious food. This means that even if people wanted to pursue a healthy diet, they would not be able to do that. Another example is pollution, both in air and water, and exposure to dangerous substances in the workplace: as healthy of a lifestyle I have, I still breathe the local air and have to go to work.

The main example is access to food. Even in the US, there are areas, described as food deserts, where it is impossible to purchase healthy and nutritious food. This means that even if people wanted to pursue a healthy diet, they would not be able to do that. Another example is pollution, both in air and water, and exposure to dangerous substances in the workplace: as healthy of a lifestyle I have, I still breathe the local air and have to go to work.

Less obvious examples are related to cultural and social norms. These include, for example, culinary traditions that might favor foods that are not supportive of the microbiome; cleaning practices: over-sanitizing could be as bad as under-sanitizing by limiting the exchange of beneficial microorganisms together with malignant ones; medical practices: overuse of antibiotics can reduce the community availability of beneficial microorganisms.

Indeed, each individual microbiome is just a small part of the community microbiome that evolves and adapts with every change in environmental, dietary, and even relationship conditions.

Individual choices for systemic health

Why is the individual microbiome an example of circular health? Because it shows how health is not only a matter of individual choices and how everything is related. My choices affect my health, but also the health of the people around me, and similarly, other people’s choices affect my health.

To conclude this post, I would like to highlight some personal choices that can affect the community microbiome.

- Second-hand smoke is extremely dangerous (also) for the microbiome

- Overuse of antibiotics affects not only the microbiome of the user, but also reduces the size and diversity of the community microbiome

- Over-sanitizing kills off good as well as bad microorganisms altering the balance of the community microbiome.

- Spending time outdoors in nature helps balance our own microbiome but also when we interact with other people, their microbiomes.

By Dr. Luca Mantegazza, Research Program Coordinator

0

0