Authors: Sydney Williams, Mark Warren, and Shivendra Kumar

For Florida hay producers, efficient nitrogen (N) management is crucial not only to maximize yields but also to protect the environment by minimizing nitrogen loss to leaching. Traditional nitrogen fertilizers can contribute to runoff and environmental harm, especially during heavy rain events. In an effort to address this issue, on-farm trials were conducted on the use of controlled-release fertilizer (CRF) in bermudagrass hay production. The goal was to assess the effectiveness of CRF in providing a consistent nitrogen supply throughout the six-month growing season while reducing nitrogen leaching. The trial was conducted on the sandy soils of the Suwannee Valley region in northeastern Florida. At the end of the season (and after each cutting), the performance of CRF was measured by comparing hay yields between fields treated with conventional fertilizers and those treated with CRF, as well as analyzing nitrogen (N) and potassium (K) concentrations in the hay.

Treatments

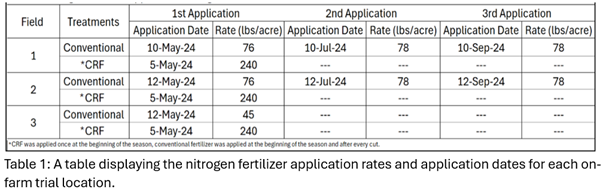

Three on-farm locations in the Suwannee Valley region were selected for the demonstration trials. The hay at these three locations was managed by the growers throughout the growing season. Each field was split in half, with one side receiving conventional nitrogen applications following the UF/IFAS rate recommendations, while the other side received controlled-release fertilizer (CRF). This design allowed for a direct comparison of how CRF performs relative to traditional methods. The table below shows the fertilizer application dates and rates at each field throughout the trial.

Results

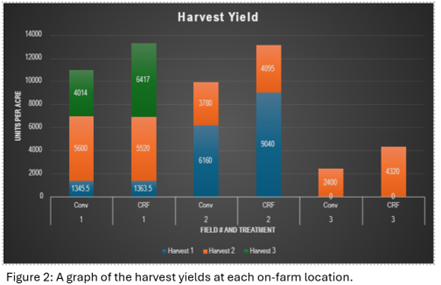

In this trial comparing controlled-release fertilizer (CRF) to conventional fertilizer, we saw promising results from the CRF in bermudagrass hay production across each on-farm demonstration.

In Field 1, yields for the first two harvests were similar between CRF and conventional treatments. However, in the third harvest, CRF-treated hay yield was 50% higher than the treatment that was conventionally fertilized. This demonstrates the effectiveness of CRF, particularly later in the growing season and availability of nutrients throughout the season.

Despite dry conditions slowing crop growth in Field 2, CRF still outperformed conventional nitrogen fertilizer. The grower was able to harvest twice, with CRF-treated hay yielding 30% higher than conventional-treated hay on the first cut, and 10% higher than conventional-treated hay on the second cut.

Field 3 was able to be harvested for the first time in July, but soon after the harvest the grower received continuous rain for two weeks, because of this he was unable to dry his hay and bale it. Due to excess moisture, the hay rotted, resulting in the grower having to burn his entire field to avoid any fungal infection. During this time, upon visual inspection, the CRF side was looking greener and had better height compared to the conventional side. After the crop recovered, the grower harvested once more and the CRF performed much better in this harvest. The CRF side yielded over 75% more than conventional-treated hay, highlighting how CRF helped to maintain nitrogen availability during rainy weather.

Hay Quality

Hay quality, measured by crude protein (CP), total digestible nutrients (TDN), and relative forage quality (RFQ), were similar for both treatments. In some cases, CRF-treated hay had slightly higher nutritional values, but both treatments produced high-quality forage.

Discussion

The yields from both CRF and conventional treatments were either similar or higher for CRF, confirming that CRF can effectively serve as a nitrogen source for hay. Additionally, the hay quality data showed comparable results across both treatments, demonstrating that CRFs do not negatively impact crop yield or quality.

Since these were non-irrigated trials, dry conditions in June and September 2024 delayed hay growth and maturity. As a result, the growers were only able to harvest hay twice in Fields 2 and 3, with only Field 1 being harvested three times.

Overall, growers were pleased with the benefits of CRF. These included reduced nitrogen leaching during heavy rainfall (including hurricanes Debbie and Helene), time savings from applying fertilizer just once at the start of the season, reduced equipment wear, lower application costs, and less soil compaction.

The high cost of CRF material remains the primary limitation. However, cost-sharing programs, which may be available through local water management districts and department of agriculture, could help offset these costs and encourage broader adoption of CRF among growers.

Acknowledgments

Lakesh Sharma, Kevin Athearn, Beth Cannon, Kaleb Kelly, Isabel McNulty, and Taite Miller contributed to this project.

1

1