15 of my formative years were spent as a swimming pool lifeguard, not only responsible for the safety of the patrons but also in charge of maintaining the pools’ water quality. Day after day, I observed parents slathering up their children with “waterproof” sunscreen, only to have the kids promptly jump into the water within five minutes, leaving behind an oily slick on the water’s surface. This was a nightmare when it came to managing the pools’ water quality, as sunscreen, mixed with sweat, ammonia, and chlorine made the pH of the water constantly change. A 2008 study by Danovaro et al. quantifies this phenomenon on a larger scale, suggesting that approximately 10,000 tons of sunscreen is produced annually. An estimated 25% of sunscreen washes off in the ocean resulting in 4,000-6,000 tons per year in water with coral reefs. In a large-scale effort to protect their coral reefs, the city of Key West, FL, and state of Hawaii both have ordinances that were to go into effect January 1, 2021, banning the sale of sunscreens containing ingredients harmful to reef health.

What the science says:

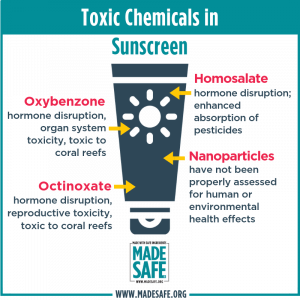

There are still many unknowns when it comes to this topic. However, studies are becoming more and more frequent. Research over the past five to ten years has demonstrated that certain organic filters/blocks such as oxybenzone and avobenzone resulted in higher levels of stress and increased coral bleaching (when corals expel their symbiotic algae from their tissues, leaving them looking white) when intentionally exposed to these chemicals in a lab setting (Downs et al. 2016, Raffa et al. 2019). Other chemicals such as octinoxate and octocrylene also serve as common sunscreen ingredients but their levels of toxicity aren’t well-established. In addition to stony coral stress, McCoshum et al. (2016) found deleterious effects of these ingredients on flatworms, anemones, and diatoms. While inorganic filters ingredients such as titanium dioxide and zinc oxide are recommended as a suitable alternative to the “benzones,” “ates,” and “lenes,” it is important to note that these substances can have effects on other marine invertebrates (Handy et al. 2008, Wong et al. 2010).

On June 30, news broke that Florida Governor Ron De Santis signed into law a bill that prohibits Florida cities banning sunscreens. The topic of sunscreen and damage to corals has received lots of attention in recent years. At this point, the Key West ordinance will not be able to move forward, but it is important to recognize the role of science and integrate it into our decision-making.

Both local and global threats to coral reefs exist. While there is not a single cause responsible for their decline, there is also not a single solution that will lead to their recovery or improved resilience. The research on sunscreen chemicals is simply the latest “insult added to the injuries” as described by Wijgerde et al. (2020) and offers us as humans the opportunity to make more informed choices when it comes to the purchase and use of products, suncare products included. No one wants anyone to get sunburned, much less skin cancer. Here are some things I suggest to keep in mind as you read this and perhaps do more research.

Banning plastic straws won’t stop plastic pollution, but even anecdotally, this movement spurred by a viral video featuring a sea turtle with a straw stuck in its nose created a much higher level of awareness of ocean issues from the average citizen. Banning these sunscreen ingredients will not stop bleaching of corals, but science clearly shows that sunblock can be a stressor to them. These ideas all tie to voluntary behavioral changes we can make, that can help protect corals and other marine organisms:

- Choose mineral-based sunscreens for use in the ocean, featuring zinc oxide or titanium dioxide.

- If you choose to use sunscreen products with the oxybenzone or avabenzone ingredients, perhaps wear them only for other outdoor activities (running, hiking, sports, sunning by the pool, etc.).

- No matter what, apply sunscreen at least 10-15 minutes early so it has time to absorb and has less of a chance of washing off.

- Wear protective clothing like UV-protective shirts and hats while in the water, minimizing the amount of sunscreen you need to use.

We can all work together to make these types of changes. There’s hope that can we can make a positive change ourselves, and maybe, just maybe, not be reliant upon legislation to do so.

References:

Adler, B., DeLeo, V. 2020. Sunscreen Safety: a Review of Recent Studies on Humans and the Environment. Photodermatology. Vol 9, pp 1-9.

Danovaro, R., Bongiorni, L., Corinaldesi, C., Giovannelli, D., Damiani, E., Astolfi, P., Greci, L., Pusceddu, A. 2008. Sunscreens cause coral bleaching by promoting viral infections. Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 116 (4) pp 441-447.

Downs, C. Kramarsky-Winter, E, Segal, R., Fauth, J., Knutson, S., Bronstein, O., Ciner, R., Jeger, Y., Lichtenfeld, Woodley, C. 2016. Toxicopathological effects of the sunscreen UV filter, Oxybenzone (Benzophenone-3), on coral planulae and cultured primary cells and its environmental contamination in Hawaii and the US Virgin Islands. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. Vol. 70, pp 265-288.

Handy, R., Owen, R., Valsami-Jones, E. 2008. The ecotoxicology of nanoparticles and nanomaterials: current status, knowledge gaps, challenges, and future needs. Ecotoxicology. Vol. 17, pp 315-325

McCoshum, S., Schlarb, A., Baum, K. 2016. Direct and indirect effects of sunscreen exposure for reef biota. Hydrobiologia. Vol. 776, pp 139-146.

Raffa, R., Pergolizzi Jr., J., Taylor, R., Kitzen, J. 2019. Sunscreen bans: Coral reefs and skin cancer. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. Vol. 44, pp 134-139.

Wijgerde, T., van Ballegooijen, M., Nijland, R., van der Loos, L., Kwadijk, C., Osinga, R., Murk, A., Slijkerman, D. 2020. Adding insult to inury: Effects of chronic oxybenzone exposure and elevated temperature on two reef-building corals. Science of the Total Environment. Vol. 733, pp 1-11

Wong, S. Leung, P., Djurisic, A., Leung, K. 2010. Toxicities of nano zinc oxide to five marine organisms: influences of aggregate size and ion solubility. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. Vol. 396 pp 609-618.

1

1