A new business supplying animal feeds to rural Niger is helping to overcome vast distances and other hurdles that constrain the productivity and incomes of goat and sheep farmers.

Though 90 percent of the rural population in Niger owns livestock, the income generated and impacts on nutrition and livelihoods remains very low. Smallholder farmers, especially women, own an average of two small ruminants in many rural parts of Niger. The main constraint to expansion is the availability of feed (cowpeas, groundnuts, and cereal bran), particularly during the dry season. Relying on crop residues, which barely meet their needs, animals are scarcely ever well fed therefore, mortality rates are as high as 30 percent, and animals are sold at low market prices. Incomes generated from livestock rarely cover the cost of investments, and farmers remain in a vicious cycle of poverty and food insecurity.

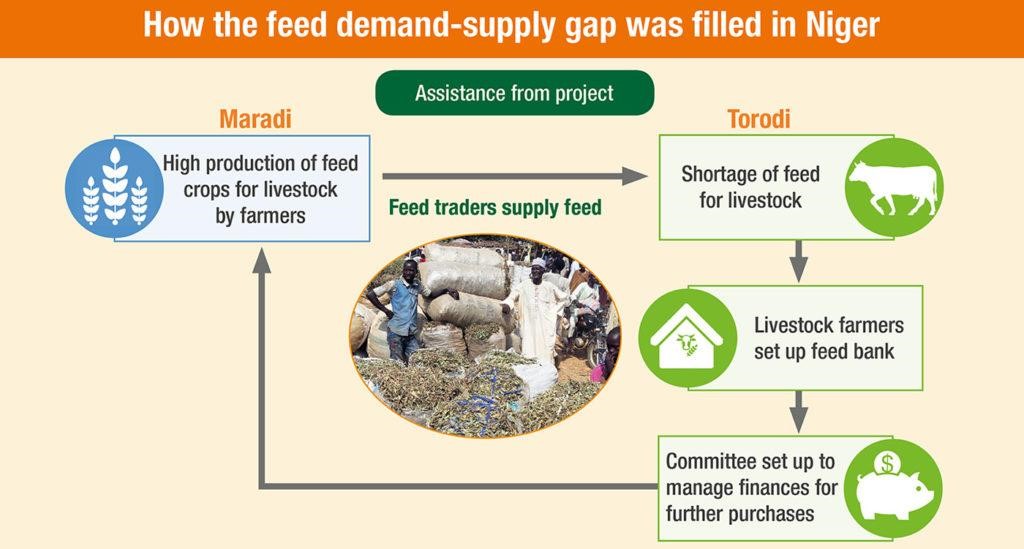

To overcome the root problem of feed shortages, new connections were fostered through a project funded by the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Livestock Systems and directed by the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT). The initiative, called Feed for small ruminants, implemented a marketing business model to connect feed producers near the city of Maradi with isolated farmers from the villages of Torodi, about 370 miles (600 km) apart.

Assisted by the project, farmers from three villages in Torodi (Sirimbana, Dioga, Ticko and Patti) and feed actors in two villages in Maradi (Banbon Kori and Karazome) created business relationships focused on supplying feed such that two feed traders from Maradi would collect, transport and sell animal feed in Torodi.

Banking the Feed

The farmers of Torodi created a feed bank to store the purchased feed on the site of a previous feed bank. Such feed banks are established, managed and owned by the community so the project assisted the community to set up a small committee to manage the revival of the new feed bank on the old site.

The feed traders from Maradi were happily surprised to note how quickly this small market grew. One of the traders, Mr. Habibou, testified: “I used to spend weeks in Niamey searching for feed markets where I could get good returns. But now I come to Torodi, and in one day I have sold all my feed. I never knew that Torodi presented such a huge opportunity for feed markets.”

Many traders compete in the large markets of Niamey, but lesser competition in Torodi combined with high demand for feed means that these traders are saving money and time. The distance to transport the feeds is shorter, and the time to sell their merchandise has been reduced from weeks to one day.

Nearly 300 male and female livestock farmers from the Torodi area are buying feed through this newly established mechanism. In addition to the greater availability of feed, Torodi farmers pay prices that are 30 percent lower than those at the markets they used previously. About 12.6 tons of feed valued at $US 3,600 has been sold through the Torodi market in less than 6 months.

More and cheaper available feed will allow livestock keepers, particularly women, to fatten more sheep and goats and earn more income.

“This feed business is an excellent initiative for our community, and now we can buy feed in our village. This contributes significantly to improving the productivity of our animals,” said Mr. Moussa Oumarou, a farmer at Torodi.

The project team and its partners are now working towards improving credit access for the various groups involved. The first plan is to link feed traders with financial institutions to allow them to purchase more feed for re-sale; a second plan is to establish credit groups (village savings groups) in each community that will allow livestock producers to access funds to purchase feeds to fatten animals. “By helping farmers to save money to be able to purchase feed during the dry season feed shortage period, we will increase the demand for feed during that period. This demand will be met by the increased feed supply from the Torodi market ” explained the project principal investigator, Dr. Vincent Bado.

This article was previously published at Agrilinks.org.

0

0