The Cooperative Extension Service was established in 1914 to address a specific problem: how to package the research and education of America’s land-grant universities and deliver it to the people. Universities published their information, but at the turn of the last century, as much as 11% of the adult population was illiterate. Direct, hands-on demonstration was a more reliable way to teach improved agriculture techniques, as the work of educators such as Seaman Knapp had proven. The challenge, in that age before electronic communication, was how to reach a mass audience in a state as large as Florida.

Farmers’ Institutes

The first Extension efforts in Florida begin in 1899 with the first Farmers’ Institutes. Held in town halls, schools or in the open air, Farmers’ Institutes combined teaching, demonstration and socializing–like a cross between a science fair and a church picnic. Speakers from the Florida Agricultural College and the Agricultural Experiment Station gave testimonials to the benefits of improved agricultural techniques. To illustrate their lectures, they used the PowerPoint tools of their day—six-foot-square charts, diagrams and blown-up photographs. Because many farming communities could only meet after dusk, the lights were often dimmed and a stereopticon lantern, lit by acetylene gas, was brought out to project images on the walls.

Source: Smathers Archive

Attendance at Florida’s Farmers’ Institutes grew at a phenomenal pace. In 1901, 22 sessions reached 3,000 people; by 1913, there were 200 sessions reaching 20,000 people. The institutes were popular because they were effective: one organizer noted in 1912 that corn production per acre had increased almost 50 percent from what it was in 1904; he argued that the knowledge gained from the Farmers’ Institutes was a major cause of the increased yield. Eventually the logistics of moving and setting up the Institutes became burdensome, and new methods of bringing the university to the people had to be explored.

Going Mobile

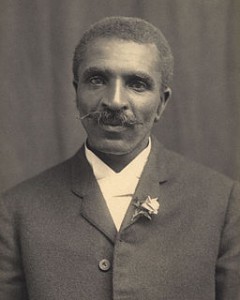

Around the same time that Farmers’ Institutes were growing in Florida, a pioneering scientist and educator in Alabama was finding a way to bring his teaching into the community. In 1906, George Washington Carver of the Tuskegee Institute designed the first “movable school.” Called the Jesup Agricultural Wagon after the New York financier who funded the project, this compact, mule-drawn cart carried farm machinery, seeds, and dairy equipment to demonstrate improved methods to farmers in rural Alabama. Of course, Carver is known to millions for his plant research, exploring hundreds uses for peanuts, including fuel, dyes and plastics. But it’s his invention of a mobile teaching unit that makes him one of the founders of modern Extension.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Taking the idea of the Jesup Wagon and hitching it to a steam locomotive, the “Better Farming Special” first chugged down Florida’s rails in the winter of 1911. In rural areas at the time, trains meant more than transportation–they were a medium, a connection to the rest of the world. The best way to bring the university to farmers and their families was by rail.

The Better Farming Special consisted of five or six cars—a day coach for instructors and lecturers, two cars full of the latest farm machinery, a car that carried improved breeds of hogs, an exhibit car and, in citrus country, a car for packed citrus products.

At each stop, lecturers from UF’s College of Agriculture, the State College for Women (now FSU), and the Experiment Station would step to the platform and deliver a 15-minute lecture about agriculture, canning, livestock and many other topics, after which the audience was invited onto the train to view the exhibits and consult with experts. In all, the Special made 71 stops around the state between November and December, reaching an average of 1,000 people per day. For many of those who came out to meet the train, it was their first real exposure to scientific research, modern agriculture and higher education.

Source: Smathers Archive

The special trains continued to run each year up until the establishment of the Florida Agricultural Extension Service in 1914, and were revived briefly in the 1940s.

From Airwaves to Apps

Extension has always been quick to adopt new technologies to deliver its educational programs to the people. In 1928 the state’s first Extension radio broadcasts began with the Florida Farm Hour over UF’s station WRUF. When television entered the picture, Extension was there in 1952 with a 30-minute program broadcast over WJAX in Jacksonville. An editorial department was added to the Cooperative Extension Service in 1961 to manage the huge output of mimeographed publications, fact sheets and brochures mailed out to each of the county offices. In Manatee County, there was even a ‘dial-a-tip’ service, where users could dial an advertised number to hear a pre-recorded message with advice about ornamental plants or garden fertilizers.

Source: Smathers Archives

With the advent of computer technology and the internet, UF/IFAS Extension has reached more people in a day than it had in its first 75 years. Electronic access to publications began in the early 1990s with a series of CD ROMs containing Extension’s entire catalog. Extension merged onto the information superhighway in 1995 with the Florida Agricultural Information Retrieval System (FAIRS). In 1998, FAIRS became the Extension Data Information Source (EDIS), which contains over 7,500 publications on all aspects of modern life. Through EDIS and Solutions For Your Life, UF/IFAS Extension’s website, each day over 27,000 people gain access to the research and education resources of Florida’s land-grant universities, and come away with research-based, practical information they can apply to their everyday lives.

The old-fashioned methods, such as Farmers’ Institutes, are still carried on today in Field Days and short courses around the state, but Extension has remained relevant because it continues to evolve with the times. Whatever technology develops over the next 100 years, UF/IFAS Extension will no doubt find a way to use it to bridge the gap between the people of Florida and the information they need to find solutions for a better life.

Sources:

Cooper, J. Francis, ed. 1976. Dimensions in History: Recounting Florida Cooperative Extension Service Progress, 1909-76. Gainesville: Alpha Delta

Chapter, Epsilon Sigma Phi,

“Farm Demonstration Trains: Florida’s Better Farming Special,” Okeechobee County Extension. Accessed January 26, 2014. http://okeechobee.ifas.ufl.edu/FarmDemonstrationTrains.pdf

Farmers’ Institute Bulletin No. 2. 1904. Florida Agricultural College and Experiment Station, Lake City, FL. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00077078/00001/43?search=farmers+%3dinstitute

“The Jesup Agricultural Wagon.” 2009. George Washington Carver Center, USDA, Beltsville Maryland. http://www.festival.si.edu/2012/Campus_and_Community/pdf/Jesup_Agricultural_Wagon_Information.pdf

0

0