This afternoon, I received an email from a PhD student at a small but hard-hitting engineering and aeronautics school across the state. His research focuses on urban trees and hurricanes, and he had come across some of my work. He reached out to discuss the available data on trees and cc’d his advisor—whom I immediately Google-stalked. I was pleasantly surprised to find that the advisor has published several papers on trees and hurricanes. None were ones I remembered seeing before (though it’s possible I skimmed past them during a hyper-focused search for supporting data on a past paper). Needless to say, the work looked extremely interesting, and I’m genuinely excited to get a fresh (i.e., engineering) perspective on trees and storms from someone outside our arboriculture and urban forestry bubble—a bubble I’m happy to be in, don’t get me wrong!

My first real hurricane experience after moving to Florida for this job was Hurricane Matthew. I distinctly remember getting a call from an excited arborist in Savannah, just south of where the storm made landfall. He had been driving around town and noticed that roof damage seemed more prevalent on properties without trees, while tree damage seemed more prevalent on properties without protective buildings.

I wasn’t in a position to go up and inventory at the time, but that conversation stuck with me (if you’re reading this—thank you for that call!). So much so that when Hurricane Irma later hit the Gulf Coast, I specifically looked at how the presence or absence of protective elements—like neighboring trees or nearby homes—impacted tree failure. (Spoiler: We didn’t see any clear pattern. The trees we looked at seemed to survive or fail as individuals, depending on their own inherent strengths or weaknesses.)

This week’s Tree Research Journal Club explores this very line of inquiry—though it does so by focusing on the home rather than the tree. Coincidentally, the featured paper is the latest work by the advisor of the student mentioned earlier, published earlier this year. I suspect it will be unfamiliar to many of this blog’s readers, especially since it’s behind a paywall. The paper is:

What was done?

The research team built a 1:20 scale model home at the delightfully acronymed Wall of Wind (WOW) Experimental Facility at Florida International University. The WOW can simulate winds up to Category 5 hurricane strength—157 mph—across a test area roughly 12 feet high and 18 feet wide. To study how trees affect wind around homes, they created four different model yards. The first had no trees at all. The second featured a high-density setup with 16 trees placed mostly along two sides of the house. The third had a medium-density arrangement with 8 trees, and the fourth had a low-density layout with just 5 trees. In this kind of research, choosing scaled-down versions of trees is always a challenge. They went with Eugenia globulus topiary and Juniperus chinensis ‘Blue Point’—essentially bonsai trees, which is kind of amazing.

After setting up the different scenarios, the researchers exposed the miniature properties to 39 mph winds from multiple angles. They measured the pressure exerted on the roof and walls using 240 pressure sensors strategically placed around the house. The study focused on how trees shielded the home from wind pressure.

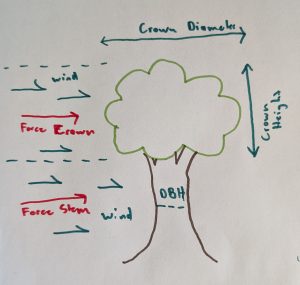

Beyond the wind tunnel experiment, the authors developed a case study to evaluate the risks posed by trees surrounding a house. The scenario involved seven hypothetical oak trees placed around a single-family home. The analysis focused on two main ways trees can fail: breaking at the trunk or being uprooted. To estimate how much wind force each tree might face, the study considered tree height, crown diameter, trunk thickness (DBH), and crown height. These forces were then compared to how much bending stress the trunk could handle before snapping—based on the wood’s strength, trunk size, and any weakening factors like knots, decay, or cavities.

What was discovered?

When the researchers compared the treeless model to the ones with trees, they found that trees—especially those placed directly in the path of incoming wind—could substantially reduce the pressure on the house. In some cases, suction forces on the roof and walls dropped by up to 50%. The trees worked by disrupting the flow of wind before it hit the building. Where a benefit was noted, trees with crowns over the roofline effectively interfered with the formation of suction vortices—the swirling, high-pressure zones that tend to cause damage at roof edges and corners. With the trees in place, those zones were smaller and less intense.

Interestingly, the benefit wasn’t uniform. In certain wind directions, the trees actually made things worse. The researchers suspected this might be due to channeling (i.e. wind accelerating through gaps between trees and buildings). They also looked at roof uplift forces (i.e., how much the wind tries to peel the roof off). Again, trees helped—except in a few directions where they didn’t. One wind angle in particular (45°) caused a spike in uplift force when trees were present.

The researchers estimated that tree failures could begin to occur at wind speeds around 40 mph, with a 50% chance of failure at approximately 112 mph. In terms of storm intensity, they projected a 42% probability of failure during Category 1 hurricanes, and between 88% and 99% for Category 5 events. While I won’t comment on the Category 5 estimates, the 42% figure for Category 1 storms seems high based on both the existing literature and my own observations. For context, the city of Tampa is home to an estimated 832,113 oak trees—primarily Quercus virginiana and Quercus laurifolia. If the model’s estimate were accurate, Hurricane Irma (a Category 1 storm) would have resulted in the loss of nearly 350,000 oaks—a truly catastrophic loss of tree cover. I explore this discrepancy further in the “Minor Grievances” section below.

That said, the authors clearly acknowledge that their model requires further refinement, including stronger support for some of its underlying assumptions. I look forward to seeing future iterations of this work.

What we like about this paper

There are a lot of things to like about this paper. First, I appreciate that it looks at both the benefits and risks of having trees near homes in hurricane-prone areas. When it comes to hurricanes, trees are often seen only as liabilities—by insurance agencies, policymakers, and much of the public. But this paper digs into a question many of us in the tree care world have wondered about: Can trees actually protect homes?

If you only focus on tree failures or insurance claims, you’re not getting the full story. Most trees make it through storms—including tropical storms and lower-category hurricanes—without any damage. And as the authors point out, we might be missing data on roofs that were spared simply because a tree happened to be in the right spot during the right storm and offered some protection

Minor Grievances

A number of assumptions underpin this type of research—it’s simply the nature of the beast. One assumption made by the research team when assessing tree failure risk was that uprooting and stem breakage are the most common modes of hurricane-induced failure, citing Duryea’s 2007 analysis of three hurricane landfalls. However, that study documented only approximately 318 whole-tree failures (they only report species with more than 20 observations) out of 7,592 trees assessed—a failure rate of around 4%. This figure aligns closely with our findings from other storms, including Hurricanes Matthew and Irma.

In Duryeas study—as in ours—less severe branch failures were far more common than whole-tree failures. Given that each tree contains dozens of primary limbs and exponentially more secondary branches, each with its own probability of failure, it is mathematically implausible for whole-tree failures to outnumber branch failures. This matters in their case study as it impacts the consequences of failure.

The Reason this Blog has Crudely-Drawn Figures

Anyone who has read this blog before knows I’m a big fan of open access publishing. The fact that ISA offers it for free through Arboriculture & Urban Forestry is amazing—especially considering the organization covers the very real expenses of paid editorial staff, printing, and maintaining the online submission system and archives. Noting these are expenses incurred by commercial publishers, I’m also fine paying $2,000 for open access when my students are submitting to journals with stronger metrics.

Ibrahim et al. (2025) filled their paper full of fantastic images that really help illustrate the methods and results. While preparing the blog, I picked out three key images I wanted to include and checked the journal’s permissions section. There was a little form to fill out, and one section read “price pending.” I watched that field with interest as I filled in the required information.

It quickly became clear that no price would appear until I fully committed and hit submit. As my finger hovered over the button, I told myself I’d be willing to spend up to $25 per image for this post.

Here’s what it quoted me:

$744!

For that price, I could have sent my lab manager to the local big box store for plywood and shrubs, recreated the images ourselves (including the purchase of our own wind tunnel—or at least a decent box fan), and still had plenty of cash left over.

Conclusions

For arborists seeking evidence that trees offer more than just the risk of falling on roofs, this paper highlights their potential protective benefits. Approaching the topic from an engineering perspective, the methods may be somewhat novel to this blog’s audience, but I especially appreciated the use of miniature trees in their model-yard wind tunnel experiment. Future pre- and post-storm assessments could be enhanced by evaluating roof damage in relation to perceived age, construction type, and the characteristics of surrounding tree cover.

About this blog

Rooted in Tree Research is a joint effort by Andrew Koeser and Alyssa Vinson. Andrew is a Research and Extension Professor at the University of Florida Gulf Coast Research and Education Center near Tampa, Florida. Alyssa Vinson is the Urban Forestry Extension Specialist for Hillsborough County, Florida.

The mission of this blog is to highlight new, exciting, and overlooked research findings (tagged Tree Research Journal Club) while also examining many arboricultural and horticultural “truths” that have never been empirically studied—until now (tagged Show Us the Data!).

Subscribe!

Want to be notified whenever we add a new post (about once every 1–2 weeks)? Subscribe here.

Want to see more? Visit our archive.

1

1