Decades of research on pruning the aboveground parts of trees have given us a solid foundation for today’s best management practices. While the science isn’t exhaustive—no one’s tested every species or situation—it’s taught us a lot about how trees grow and respond. We know, for example, that flush cuts are bad news compared to cuts that respect the branch collar, which help trees compartmentalize wounds and reduce decay. We’ve also learned the long-term value of formative pruning, especially when shaping strong structure early in a tree’s life. And we understand how different types of cuts—heading, reduction, removal—affect trees in distinct physiological and structural ways.

But when it comes to the belowground parts of trees, our knowledge drops off fast. Most of what we know about root loss comes from studies simulating construction damage—things like trenching or grading that disturb roots a set distance from the trunk. Those studies have been useful, but the results can be hard to generalize since root systems are anything but predictable.

The good news is that arborists today have more tools than ever to map and locate roots before a project begins. That means we can make more informed choices about which roots to preserve and which can safely be cut to make way for foundations or footings. The bad news? There’s still not much research that directly guides those decisions.

That’s why we at Rooted in Tree Research were especially excited to see the latest work out of New Zealand from Andrew Benson and Justin Morgenroth.

Benson, A.R. and J. Morgenroth. 2025. Optimising root pruning responses in mature Platanus x acerifolia trees. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 113:129103.

What was done?

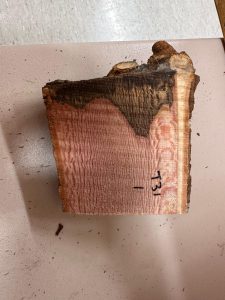

In this study, the authors explored how cut type and time of year affect root pruning outcomes. Specifically, Benson and Morgenroth examined root regrowth—the number, diameter, and location of new roots—and the amount of discoloration following two types of cuts: heading cuts (made between branching points) and reduction cuts (where a main root is cut back to a smaller lateral root). Half of the cuts were made in fall and the other half in spring.

As the title suggests, the treatments were applied to mature London plane (Platanus × acerifolia (Aiton) Willd.) trees. All cuts were made by hand saw on air-excavated root systems, making this study especially relevant to real-world situations where trees are growing close to construction projects and arborists are carefully assessing root locations to minimize damage while creating space for footings or foundations.

What was discovered?

Interestingly, the time of year didn’t affect how many new roots formed after pruning—but the type of cut did. Trees that received heading cuts produced more new roots than those with reduction cuts made back to a smaller root. Both types of cuts, however, triggered a strong regrowth response. On average, heading cuts produced about 26.9 new roots, while reduction cuts produced 19.4. The median diameter of these new roots wasn’t affected by pruning method or timing. Overall, root regrowth was greatest within the first centimeter (about half an inch) behind the cut, and this new growth tended to concentrate on the underside—or bottom half—of the root. In contrast to root regrowth, the season of pruning did have a significant impact on decay. Roots pruned in spring showed more discoloration than those pruned in fall.

What we like about this paper

This paper tackles a very practical research question and does so with a comprehensive—but not overly complicated—set of measured responses: namely, root regrowth and discoloration or decay. The organization is consistent and logical throughout, making it easy to follow and interpret the results. Also… they list their actual hypotheses right there in the introduction—like real scientists! (If you’re reading this and feel called out, don’t worry—this is as much a commentary on my own shortcomings as anyone else’s.) The figures and charts are crisp and modern, giving off a definite “I spent half a day coding this in ggplot2” vibe.

It’s also worth noting that this research was funded by the TREE Fund. Given how competitive their grant process is each year, you can be confident that the projects they support are both scientifically sound and grounded in real-world needs.

Finally, the authors clearly know their audience. The research question itself is one many arborists have likely pondered, and they take the time to spell out the practical implications of their findings in the conclusion. That’s something I’m going to start incorporating into my own papers—even when it’s not required by the journal.

Minor grievances

As should be clear from my earlier comments, I absolutely loved this paper. It was a joy to read—thoughtfully composed, thoroughly researched, and polished in a way that’s increasingly rare in today’s publish-early-and-often climate.

My only grievance? The steadfast refusal to use the letter “z” (zee, not zed) in words like optimizing, and the rogue insertion of stray “u”s in words like discoloration. This stylistic choice was consistent throughout the paper, including the title and subheadings. Benson, who was born in Wales, assures me this is “the correct way” to spell these words. I remain unconvinced.

How can an arborist use this research?

As noted, the authors take care to present a clear set of conclusions specifically for practitioners. These appear at the very end of the paper, laid out in bullet points. They are paraphrased below:

- Prune in fall to minimize discoloration and decay.

- If the goal is to reduce new root regrowth (e.g., pruning for a sidewalk conflict), use a reduction cut.

- If the goal is to maximize root regrowth (e.g., pruning before transplanting or during certain construction activities), use a heading cut.

About this blog

Rooted in Tree Research is a joint effort by Andrew Koeser and Alyssa Vinson. Andrew is a Research and Extension Professor at the University of Florida Gulf Coast Research and Education Center near Tampa, Florida. Alyssa Vinson is the Urban Forestry Extension Specialist for Hillsborough County, Florida.

The mission of this blog is to highlight new, exciting, and overlooked research findings (tagged Tree Research Journal Club) while also examining many arboricultural and horticultural “truths” that have never been empirically studied—until now (tagged Show Us the Data!).

Subscribe!

Want to be notified whenever we add a new post (about once every 1–2 weeks)? Subscribe here.

Want to see more? Visit our archive.

5

5