The icon of the south, a sweeping live oak draped in the filamentous curtains of Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides). Shrouded in misconception, dripping in cultural significance and once upon a time adding the fluff to the cushions of early automobiles, Spanish moss is often at the center of tree conversations in local Extension offices. The question comes up at least once a month, is Spanish moss killing my tree? What good does it do? Can I remove it? How did it get there? I find myself repeating the same mantra, “Spanish moss is an epiphyte, in the bromeliad family, related to pineapples, no it doesn’t hurt your tree, no don’t pay someone to remove it, yes it does seem to show up in greater quantities on stressed trees, no it’s not responsible for their demise.”

In true ‘Show us the Data’ fashion, we will be looking at the stressed tree/Spanish moss conundrum in an upcoming series, but in the meantime, I wondered what I could find out about the ‘usefulness’ of Spanish moss. To answer this question, I started to browse through what I could find on the uses of Spanish moss, leaning into its possible functions as an indicator of air quality. A review of several papers led me to a foundational paper for the current use of plants as biological indicators in environmental geochemistry and air quality assessment. This 1973 USGS Study by Shacklette and Connor will be the focus of this Tree Research Journal Club:

Shacklette, H. T., & Connor, J. J. (1973). Airborne chemical elements in Spanish moss (Professional Paper 574-E). U.S. Geological Survey. https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/0574e/report.pdf

What was done?

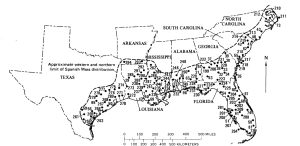

The research team collected samples of Spanish moss from 123 locations

across the southeastern United States. Randomized samples were cleaned, oven dried and then pulverized. The researchers used a wet digestion method to analyze for arsenic, mercury and selenium. Samples were also placed in a muffle furnace at a temperature of 550 degrees Celsius for 24 hours. Various methods including emission spectroscopy and colorimetry, were then used to analyze the ash for concentrations of other elements.

In a process that is mind boggling for this blogger to consider, the researchers then fed their resulting data into a computer for analysis using punch cards (!!) Relative concentrations of the samples were represented visually within a range and then spatially displayed on a map using circular symbols plotted to the geographic location of the sample.

What was discovered?

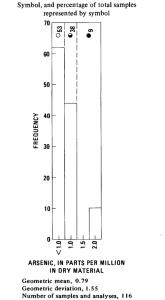

The morphology of Spanish moss, its lack of roots and absorption of moisture and nutrients directly from the atmosphere through its scaly, filamentous leaves, makes it an effective collector of airborne particles and dissolved elements. This analysis identified 38 chemical elements in samples of the Spanish moss, revealing distinct spatial patterns.

Industrial and urban areas showed elevated concentrations of heavy metals such as lead, arsenic, cadmium, and zinc. These elements are commonly associated with combustion, smelting, and vehicular emissions (Remember that this study took place prior to the broad adoption of unleaded gasoline).

In contrast, elements like calcium, magnesium, and potassium, which are more biologically essential and geologically widespread, were more evenly distributed. Trace elements such as vanadium, barium, and chromium also displayed regional variability, reflecting both natural geochemical backgrounds and anthropogenic influences. In an interesting proof of concept, tin is often found at too low of concentrations to be detected, however, four samples of Spanish moss showed detectable tin. The samples which were all from the same geographic region in Texas had the only detectable tin out of all samples. Since the samples were randomized, the probability that these samples contained tin by chance is near zero. (These samples were taken from a region near the only tin smelter in the southeastern U.S.) By mapping these concentrations and correlating them with land use and environmental conditions, the study demonstrated how Spanish moss could serve as a low-cost, effective tool for monitoring air quality.

What we like about this paper

The research presented in this paper is rigorous, and comprehensive while also being a great example of applied science. As an early and influential example of biomonitoring, it offered insights that would inform later work in environmental geochemistry and pollution tracking. (It was also an exercise in concentration for this blogger who just narrowly avoided following punch cards down a rabbit hole.)

Conclusions

While we no longer punch code onto cards for our statistical analyses, biological indicators of environmental health are still widely used and variously applicable. Lichens, zooplankton, fungi and several plant species are currently used in environmental monitoring programs. In urban forests of the Southeast, Spanish moss is a ubiquitous feature throughout suburban, urban and industrial areas, living for decades at least and potentially much longer, it can serve as a record over time for air quality and atmospheric condition. So, if you have Spanish moss on your tree, leave it be and keep your eyes peeled for our future series from Show us the Data on this epiphyte and its host plants.

About this blog

Rooted in Tree Research is a joint effort by Andrew Koeser and Alyssa Vinson. Andrew is a Research and Extension Professor at the University of Florida Gulf Coast Research and Education Center near Tampa, Florida. Alyssa Vinson is the Urban Forestry Extension Specialist for Hillsborough County, Florida.

The mission of this blog is to highlight new, exciting, and overlooked research findings (tagged Tree Research Journal Club) while also examining many arboricultural and horticultural “truths” that have never been empirically studied—until now (tagged Show Us the Data!).

Subscribe!

Want to be notified whenever we add a new post (about once every 1–2 weeks)? Subscribe here.

Want to see more? Visit our archive.

3

3