Florida Commissioner of Agriculture Adam Putnam has said that

in a state as diverse as Florida, water is the closest thing we have to a shared identity.

I’ve been travelling up and down Florida’s Gulf Coast the last two months learning about water issues in our Extension district. I’ve been in the beautiful citrus groves of rural Hardee County, in the Florida Friendly Lawns of urban Manatee County, in the middle of Sanibel Island during Tropical Storm Colin, and along the banks of the tea-colored Alafia River. I’ve listened to citizens voice concerns about Lake Okeechobee overflows carrying pollutant-laden waters to Florida’s Gulf coast and heard questions about how to manage those flows in a way that meets the needs of both agriculture and city residents– a challenge Florida will likely face well into the future. I’ve stood in fields with farmers and other agricultural producers anxious about our state’s ever growing need for groundwater and seen their quickness to do their part in helping by adopting best management practices. I’ve talked to city and county elected officials who need to assure their citizens that their water supplies are safe. And I’ve participated in on the meetings that emerge from necessity when we find out that those supplies are in fact contaminated, polluted, or degraded. What I’ve learned is that Floridians think deeply about water. We are aware of water as our shared identity; we are collectively aware of the needs to ensure safe, clean water supplies for ourselves and the future; and we are committed to learning and being involved in needed discussions and behavior changes.

In the next few weeks, I hope to write about some of the BIG ISSUES facing water supplies in the Extension South Central District (which includes the Gulf Coast counties from Pasco down to Collier, as well as Polk, Hardee and DeSoto). While I focus on this part of the state, in many ways the issues we face here are found in other parts of the state as well. Today’s blog focuses on regional water supply and Basin Management Action Plans (BMAPs), which are the documented action items put into place once a water body has been found “impaired” by a given pollutant.

Big Issue #1 REGIONAL WATER SUPPLY

We get almost all our water from groundwater, and it’s time to reconsider that. We need to conserve and we need to diversify our water portfolio. Groundwater withdrawals have impacted the Upper Floridan Aquifer throughout much of the district. Within the Tampa Bay Water Use Caution Area (WUCA) and the Southern WUCA, depressed aquifer levels have led to saltwater intrusion and reduced flows and levels in surface waters. As we pump and pump groundwater, saltwater from the Gulf creeps in, mixes with and contaminates our freshwater drinking supplies. The two WUCA’s in blue in Figure 2 are where water supplies “are or will become critical in the next 20 years.” Southwestern Hillsborough County and western Manatee County comprise the Most Impacted Area (MIA) of the Southern WUCA, a 708-square mile zone where saltwater intrusion is especially problematic.

To address groundwater drawdowns, SWFWMD is placing major emphasis on water conservation messages, exploring alternative water supplies, and continuing the Facilitating Agricultural Resource Management Systems (FARMS) Program, which provides up to 75% cost share for implementation of agricultural BMPs that reduce groundwater consumption.

The development of alternative water supplies—such as through the storage of reclaimed water, aquifer storage and recovery, indirect potable reuse, and saltwater desalination—is a major area of focus for SWF and SF Water Management Districts right now. For example, SFWMD recently opened up cooperative funding to support alternative water supply projects. SWFWMD has a goal to increase the beneficial reuse of reclaimed water and to explore the feasibility of aquifer storage and recovery, which involves injecting either reclaimed water or surface water into the aquifer and storing it there for future use. Injecting reclaimed or surface water into the potable zones, as opposed to the non-potable zones, of the aquifer would provide the most aquifer lift and thus serve as the best mitigation against saltwater intrusion. However, this requires the ability to treat reclaimed water to very high water quality standards, so it may be cost prohibitive and face permitting challenges.

Big Issue #2 BMAPS

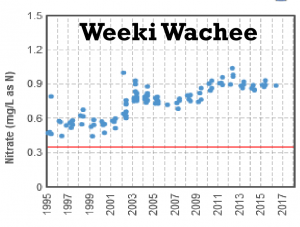

The US Clean Water Act requires states and tribes to maintain lists of “impaired waters,” or those waters that are not able to serve their designated uses because of harmful levels of pollution. For example, Weeki Wachee Springs is listed as impaired because of excess levels of nitrate-nitrogen (Figure 3). While the Springs itself is located outside of our Extension district, its watershed extends downward into eastern Pasco, so actions here affect outcomes in the Springs.

Once a water body is listed as impaired, a total maximum daily load (TMDL) is established for the causal pollutant. A TMDL is a pollution budget that sets the maximum level of a pollutant that can be in a water body and allocates necessary reductions to sources of that pollutant. Potential pollutant sources may be point sources like wastewater treatment plants, or non-point sources such as stormwater runoff. After establishment of a TMDL, a Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) may be developed to outline a comprehensive set of strategies for implementing the pollution reductions called for in the TMDL. These strategies may include permit limits on wastewater treatment facilities, financial incentives for conservation activities, urban and agricultural best management practices, or site remediation activities.

There are 7 BMAPs within the South Central Extension District, given here with their listed pollutants:

- Lake Okeechobee, phosphorus

- Hillsborough River, fecal coliform

- Alafia River, nitrogen & fecal coliform

- Manatee River, fecal coliform

- Caloosahatchee Estuary, nitrogen

- Everglades West Basin, nitrogen

- Weeki Wachee (pending), nitrogen

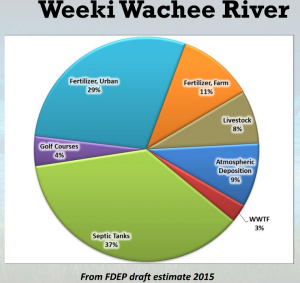

At University of Florida/IFAS we brand ourselves as providing “solutions for your life.” When I think about these 7 BMAPs, I’m struck by the tremendous opportunity that we have to address water quality issues and to provide the citizens of Florida with solutions! County and state Extension agents are an army of on-the-ground science ambassadors who provide the knowledge transfer necessary to implement BMAP goals. For example, in the pending Weeki Wachee Springs BMAP, the FL Dept. of Environment Protection (DEP) has identified urban fertilizers and septic tanks as the leading contributors to nitrogen pollution (Figure 4). IFAS programs such as the Water Stewards Program and Florida Friendly Landscaping play key roles in getting the message out about how to prevent that pollution. We also see the opportunity here for potential new programming, in areas such as septic system maintenance. Under the recently passed Florida Springs and Aquifer Protection Act, municipalities within this Weeki Wachee BMAP will be required to adopt fertilizer ordinances and to implement a program of septic system remediation. Our state and county agents can be the “go to” personnel as elected officials and citizens seek advice on how to implement BMAP goals and legislative requirements.

What are your thoughts on the BIG ISSUES discussed here? I welcome your comments. The next BIG ISSUES blog will look at the three National Estuary Programs in our District. Florida has four Estuaries of National Significance, more than any other state, and 3 of those 4 are right here in our district!

0

0