While we have luckily avoided direct impacts from recent hurricanes Helene and Milton in northwest Florida, we still felt their massive size and power. These storms whipped up the entire Gulf of Mexico, pushing creatures rarely seen above water onto the beaches. Just after Helene blew past, a local resident sent our office photos of a large unidentified invertebrate he saw in the Perdido Key area. We were able to identify it as a sponge, reminding me of when I received similar pictures 4 years ago. In September 2020, Hurricane Sally churned up the bottom and deposited sponges all over our beaches.

Last week, I was notified of another curious animal found out at Big Lagoon State Park. It was small, red, and wormlike, with its head buried in the sand. Unfamiliar with this species, I reached out to a panel of experts—my fellow natural resource Extension agents—and a marine invertebrate professor at UWF. By consensus based on what we could determine from the photo, we deemed it a snake eel.

Of particular interest to me was that the first example ever described—the holotype—of one species of snake eel was “a single, partly digested example, 31 inches long, from the spewings of snappers . . . on the Snapper Banks at Pensacola” in 1892.

(1984), pp. 32-44

As you can imagine, using partially digested snapper puke is not the easiest way to identify a newly discovered organism. It took the better part of a century for biologists to sort out the assorted snake eel species from each other. Particularly in the early days, but even now, field biology has a lot in common with archaeology. Scientists find parts and pieces of animals on the ground or in the water, often far from their original habitat. Using clues from body shape and type, or comparing them to pieces found elsewhere, we can come up with a more complete picture and description.

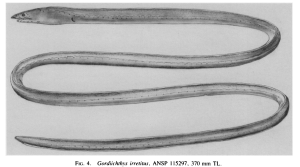

Unless you’re a diver, these eels are not particularly familiar to anyone. They live offshore, at depths of 50-1200 feet. Larger, more familiar eels like the moray are known to back their tails and bodies into crevices, hiding among hard structure like coral or oyster reefs. However, these snake eels are burrowers. They live buried in the mud and sand of the sea bottom and have special adaptations for living in this habitat.

The eel’s head is elongated and strong, with nasal passages flattened and adapted to burrowing either head or tail first. Its long, skinny body is extremely muscular, including between the ribs and vertebrae. Its mouth and teeth point backwards, for ease of reaching out, grabbing prey, and pulling it back into a burrow. While this small one found recently is reddish in color, larger, more mature snake eels are predominantly white with black bands encircling their bodies.

So, next time a tropical storm makes its way through the Gulf, walk the beaches! There’s no telling what mystery creature the next hurricane will churn up and drop on our shores.

9

9