As I write this article it is mid spring, and the rays are bedding on the edges of our seagrass beds. The most common species seen is the Atlantic Stingray (Dasyatis sabina). They are often found in the sandy areas near the grass where they bury in the sand to ambush potential prey. This time of year, their numbers increase as the females are preparing to releasee their young in summer. Mating occurs in early spring and the females will deliver live young1.

According to Hoese and Moore2, there are eight families and 18 species of rays and skates found in the Gulf of Mexico. These are cartilaginous fish found in the same class as sharks but differ in that their gills slits are on the ventral side (bottom) of the body and their pectoral fins begin before the gill slits do on the side of the head. Most are depressed (top to bottom) and appear like pancakes, but not all of them. Sawfish and guitarfish appear more like sharks than rays.

Of the 18 species listed, seven can be found in the estuaries and may be associated with nearby seagrass beds. Two are species of sawfish, which are rare in our bays these days.

Photo: University of Florida

There are two members of the eagle ray family, the cownose ray and the eagle ray, which can be found in our bays. These resemble manta rays but differ in that they lack the characteristic “horns” of the manta (often called the Devil Ray because of them) and they do possess a bard on their tail, which manta’s do not. These are more pelagic rays spending their time swimming in the water column and hunting for buried food.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant.

The butterfly ray does resemble butterflies in shape having wide “wing-like” fins and a very small tail. It behaves similar to stingrays burying in the sand and ambushing smaller prey.

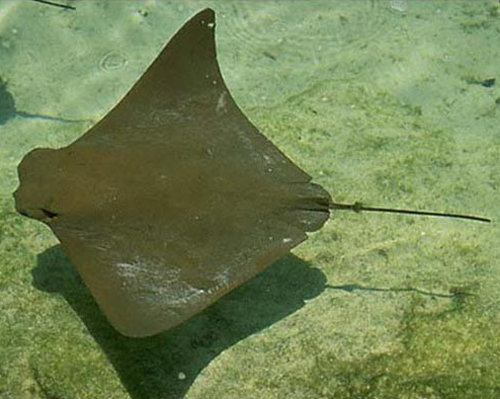

Two of the more familiar stingrays are found in our grassbeds, the Atlantic Stingray and the Southern Stingray. The Atlantic Stingray’s disk is more round in shape while the Southern Stingray’s is more angular shaped. The Southern Stingray is larger (disk width about five feet, Atlantic disk width is about two feet) and prefers estuaries with higher salinity. The Atlantic Stingray is very common and can tolerate freshwater, thus is common throughout the bay.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History.

Stingrays are notorious for their venomous bards and painful stings. They actually try to avoid humans and are frequently spooked by our activity fleeing as soon as they can. However, there are times when people accidentally step on one buried in the sand, or hiding in the grass at which time they will flip their whip-like tail up and over to drive their barb into your foot forcing you to move it – and you do move it – while you yell and scream. The ray then will swim away and can regrow a new barb.

The bard is a modified tooth. It is serrated on each side and there is a thin sac of venom along the flat side of the barb. When it penetrates your foot there is pain enough there. But the natural reaction of your body to an open wound is to close it, this reaction can pop the venom sac and release the toxin. The chemistry of the toxin is not life threatening to humans but is very painful. This experience is something you do want to avoid.

Like their shark cousins, rays do have rows of small teeth which they use to crush small invertebrates including shelled mollusks. They lie in the sand to ambush prey moving in and out of the seagrass beds. They possess two spiracles on the top of their heads which provide water to the gills when they are lying on the seafloor or buried in it.

Like sharks, males can be identified by the two claspers associated with the anal fin and the females usually have two uteri where the young develop. In skates, and some other rays, the young are deposited into the environment within a hardened egg case often called a “mermaids purse”. We see these washed ashore in the beach wrack. Young stingrays usually develop within the female and are born “live” in summer.

Though there is fear of this animal from some seagrass explorers they are a small threat unless you step on one. To avoid this, when in and around the sandy areas of a grassbed, move your feet in what we call the “stingray shuffle”. This is sliding your feet across the surface of the sand instead of stepping. The pressure generated from this movement can be detected by the ray several feet away and they will immediately move away.

Despite the fear, they are amazing creatures and play an important role in the overall health of the grassbed community.

References

1 Snelson, F.F., Williams-Hooper, S.E., Schmid, T.H. 1988. Reproduction and Ecology of the Atlantic Stingray, Dasyatis sabina, in Florida Coastal Lagoons. Copeia. Vol. 1988, No. 3 (Aug 1988). Pp. 729-739.

2 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M University Presse. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

0

0