Echinoderm means “spiny skin” and some members of this phylum are very spiny. The sea urchin is almost like a round shaped roaming cactus on the seafloor. Many think the spines are venomous, and some are, but not all. Though it is not a real diverse group, about 6000 species compared to the 80,000 mollusk and 800,000 arthropods, it is a real interesting group – in many ways. Let’s take a look at them.

Image: Study Blue

First, they are radial/coelomates. You might remember from lesson 1 that the most primitive form is radial/acoelomate. This form developed into bilateral/acoelomates, and eventually bilateral/coelomates. But the echinoderms stepped back to the radial form. The fossil record suggest they appeared on the planet 600 million years ago, about 100 million years before the mollusk and arthropods, but at about the same time as the annelid worms (which are also bilateral/coelomates). It appears to be a group that just missed that train, maintaining the radial symmetrical form.

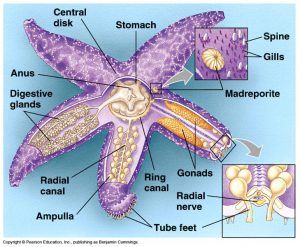

Being radial means, they do not have a distinct anterior and posterior end (head and tail) but do have a dorsal and ventral side (top and bottom). When you pick up a sea star, you can tell where the top and bottom are but not the front and back. They are said to be pentamerous radial, meaning they typically have five arms radiating out from a central disk portion of the body – but some sea stars have up to 20 arms. Though this is considered more primitive, it has not slowed down the echinoderms.

The do have a coelomic cavity, so they do have internal organs – including a digestive, reproductive, circulatory, and nervous organs. They do have a complete digestive system, including both a mouth and an anus. However, they are missing an excretory system and must release waste through the skin. They have an active nervous system, but a true brain does not exist. Rather, they have a series of nerves running through their skin connected to a nerve ring that incircles the central disk area of the animal. They are well aware of what is going on around them. Some have eyespots at the ends of their arms that can detect light and all have a means of chemoreception (taste and smell). They can also control movement within the arms.

Photo: Flickr

A unique feature of their coelomic cavity is the presence of a water vascular system, not found in any other animal. This is a series of water filled canals running through the coelomic system of the echinoderm. It begins on the dorsal surface with a structure called a madreporite (sometimes referred to as the sieve plate). Water can be drawn into the animal through this plate into a series of canals leading to the ring canal (encircling the central disk). From there the fluid runs down a canal that extends each of the five arms ending in sacs that extend beyond a ventrally open grooved. These extend sacs are called tube feet and are slightly concaved. When full of water and rigid, these tube feet act as suckers and grab onto the substrate to pull them along. This is their form of locomotion and because of this, all echinoderms are benthic – live on the bottom. It is important to note here also, they are all marine. There are no freshwater echinoderms and they do not exist in low salinity parts of the estuary.

There are male a female echinoderms, but fertilization is external, both sexes releasing their gametes into the water column. But, during fertilization, they can produce millions of fertilized eggs. They do have the ability to regenerate body parts including severed arms.

There are four major groups of echinoderms. (1) The sea stars – once called starfish, (2) the brittle stars, (3) the urchins (which include the sand dollars), and (4) the sea cucumbers.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Sea stars are the most famous group. There are about 1600 different kinds worldwide. The mouth is located on the ventral side in the middle of the central disk. In general, they are carnivores and feed on a variety of benthic invertebrates, and occasionally fish. They lack teeth but can grab the prey using their tube feet and can invert their stomach externally of the body in a process called evisceration that allows them to consume snails, bivalves, corals, and other animals encased in protective shells. Several have become very problematic within oyster beds or coral reefs.

Photo: NOAA

Brittle stars differ from sea stars in that their extended arms are very thin and brittle. They lack the ventral groove along each arm and their tube feet are not important for locomotion. There are about 2000 different kinds and most like muddy sediments. They are quite common on the bottom of estuaries near the mouth of the bay where salinities are high enough. They move quite fast pulling themselves along in the mud. These animals are more scavengers and filter feeders.

Photo: NOAA

Photo: Florida Sea Grant.

The sea urchin group includes the sand dollars and the sea biscuits. The appearance of this group is very different. Imagine a sea star laying on the ocean floor. Taking the end of each arm, imagine rolling this over the top to where the tip of each meets over the dorsal side of the central disk. The animal would now appear to look like a round ball, more of what a sea urchin looks like. The tube feet extend in all directions are important in feeding and locomotion. The sea urchins have long spines called quills that can be very painful, in some species venomous. They do use their eyespots to detect shadows and move their quills into position to protect themselves from predators. The sand dollars are basically round urchins that have been flattened into a disk. There are about 900 different kinds of urchins and sand dollars found around the world. They feed differently than the sea stars. They are more herbivorous using five plate like teeth called Aristotle’s Lantern. These teeth pinch together scrapping algae from rocks and shells. They can tear pieces of seaweed and consume them but prefer to feed on torn bits on the seafloor. Sand dollars feed on bits of organic debris within the sand they bury in.

Photo: NOAA

The sea cucumbers are one of the strangest of the echinoderms. They do not appear to be related to them at all. They literally look like cucumbers lying on the ocean floor. No sign of radial symmetry, no five arms, nothing hinting they are related. But they are. Imagine taking our rolled sea star that formed the sea urchin form and elongating that from top to bottom forming a tube. Now lay that tube on its side on the seafloor. You have a sea cucumber. They do use their tube feet to move. They plow their way through the ocean floor looking for organic material to feed on – deposit feeders. Some species are famous for their means of defense. When irritated by a predator they can face their anus towards the problem excreting a series of sticky threads (like a net) all over the predator. In some species these threads are just a sticky mess and enough to make the would-be predator leave. In others there is actually a toxin associated with them. Other species will face the predator and eviscerate their digestive and respiratory organs outside of their body. This display usually forces the predator to try another prey and they can retract these organs back into their body.

A couple of last notes on this group before we leave the invertebrates.

One, echinoderms are the only invertebrates with an internal skeleton. The hard-bony structure is called a test, and this is what most people find when walking the beaches looking for sea shells.

Two, their embryonic development mimics that of the vertebrates and, because of this, many marine biologists believe it was the echinoderms that gave rise to the vertebrates. We will explore the vertebrates next month.

0

0