Ever since my father gave me a dive mask when I was in the 5th grade, I knew what I wanted to do for a career. I placed the mask on and went into what I called “the drop-off” in Santa Rosa Sound (it was probably 10 feet deep – but to a 5th grader… that was the “drop-off”). Th world went silent, except for the snapping of small shrimp and noisy fish, and the abundance and colors of the fish swimming around was amazing.

In middle school I was an assistant in the library one period, and I would spend hours thumbing through books on oceanography, looking at the pictures of scientists standing on catwalks along the side of research ships deploying all sorts of scientific equipment. I decided then that marine science would be my life calling.

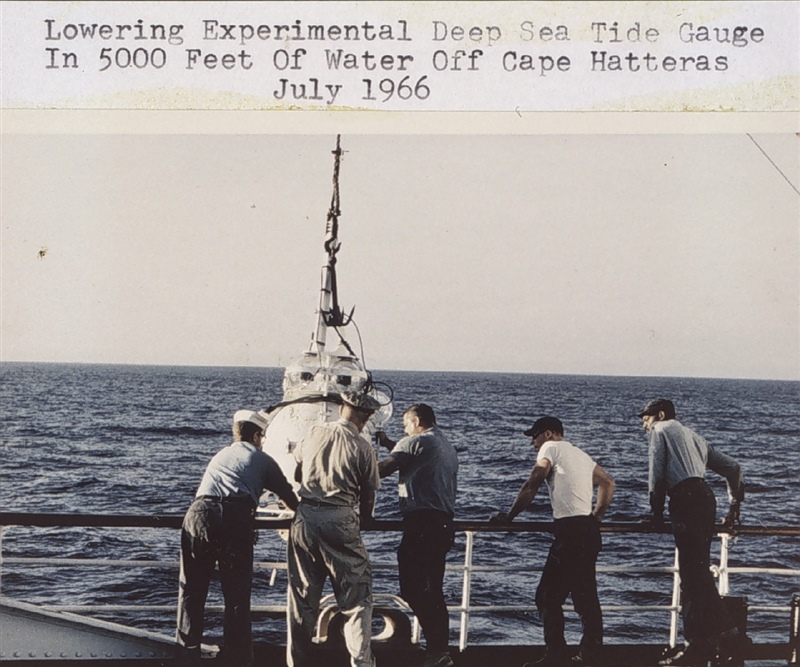

(Photo: NOAA)

I took marine biology in high school and in college landed at Dauphin Island Sea Lab studying marine science seeking a degree. Though Sea Lab did plenty of work offshore, they also worked on one of the larger estuaries in the United States – Mobile Bay. We spent many hours working in the bay both from small and large research vessels and I became very interested in the ecology of these amazing systems. I did get some offshore work sampling the bottom and tagging sharks, but my interest did turn to the estuary. And that is where I have spent the last 38 years of my career as a marine science educator. But the dream of doing open ocean work on a research vessel, those photos I saw when I was in middle school, never left me… they were still a big dream for me.

In the summer of 1994, after had received my masters degree, I got my chance. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) owns a fleet of research vessels around the country that make routine cruises to collect all sorts of oceanographic data. They often take on “co-operators” to assist the science team with this. I was invited to be a co-operator for a seven day cruise conducting a bottom trawl survey to assess what species often become bycatch in the offshore shrimping industry. My time at sea was about to begin. The dream was coming true.

The ship I would be heading out on was the NOAA research vessel R/V Oregon II. This is a 210-foot vessel docked at the NOAA lab in Pascagoula MS. The morning I arrived I was very excited. There she was, the “O 2” (as they called her) tied to the dock with a gangway heading up. The first thing I noticed was how all of the other members of the cruise were grabbing their seabags and running to the ship. I was puzzled by this… certainly there were assigned bunks for everyone… certainly there was plenty of space and they were not going to turn someone away… why were they all running? I would later find out and will share that in another part of this series – but I decided to grab my bag, kiss my wife, and get onboard as quickly as possible.

I found my bunk, tossed my seabag on it, and met my cabin mate for the next seven days. The “O 2” was a big ship and so we walked around taking a look at how it was all laid out. There were numerous bunks, a galley with a TV, a dry bay where the computer rooms were, and any “dry work” would be done. There were strict rules about EVERYTHING being dry in this room – no wet shoes – no wet anything! There was a wet bay as well and, as you can guess, this is where you could have wet clothes and shoes, this is where the fish would be processed. Beyond that was a storage room with all sorts of equipment that I remember seeing in those middle school library books, and eventually a door that led to a large deck on the stern of the ship. Here is where the large nets would be deployed and retrieved. Here is where the catwalk was where you would deploy equipment over the side. It was all pretty cool. My heart was pumping hard. We had done nothing to this point, but it was still very exciting.

We were all called to the science meeting. In those days the lead scientist was known as the “chief scientist” – today they call them the “principal investigator” or “PI”. The PI for this cruise was an African-American gentlemen who would be going over the science side of this trip with us and explain our job. I mention that he was African-American only because many African-American youth do not think this is a career for them, there is no place for them. There are PLENTY of jobs in this industry for everyone. In this case he was running the show!

He explained that our job was to drag an otter trawl on the edge of the continental shelf collecting marine life to get a better understanding of offshore shrimpers might collect as bycatch. This information could be used to help manage the fishery more sustainably. The nets would be deployed around the clock – 24/7 – during the cruise as we would all be assigned to shifts. Mine was 4-8; that was 4-8am and 4-8pm. We were to be on the back deck at your assigned time. If I wanted food or a shower, do that before, you needed to be on station at your assigned time.

Your job depended on where we were in the process. If a haul was coming in… you were to first shovel the marine life into large plastic baskets on deck. These were to be lifted to a large spring scale for weight – that recorded – you would dump the contents onto a conveyor belt that would move the mass into the wet bay. Once all of the fish had been weighed you were to go into wet bay and begin sorting by species into smaller baskets. Once the sorting was all done, you were to measure EVERY fish and sex every fifth one. You measured them using a machine similar to the one that reads the bar codes on your groceries at the grocery store. You just placed the fish down on the glass screen, you would hear a “beep”, and you would toss it into another large basket. Every fifth one would go into a different basket to be sexed later. When all was done, there was a shoot that went off the starboard side of the ship that sent the fish back into the Gulf of Mexico. When your shift began, you may be in the middle of processing a haul and you would jump in wherever you were in the process.

You might think of this as a waste of marine resources, and it is. However, this study helped NOAA with the management of the fisheries on a large scale – sort of the idea that a few will die for the good of the whole. It is a hard pill to swallow when you see all of the fish being dumped back in, but good science was coming from it.

We were told that who was ever on shift in the morning might be asked to collect a plankton sample for chlorophyll a analysis. Chlorophyll a analysis gives you an idea of the biomass of phytoplankton in the ocean. These are small celled green plant-like creatures that serve as the “grass of the sea”. Just as plants are crucial for all life on land, so to are they at sea. To do this, you would go to the portside of the ship, about mid-ship, and deploy a plankton net over the side on a line. The net was pulled for three minutes and then retrieved. The water sample was filtered through filter paper using a vacuum pump, that filter paper was then wrapped in aluminum foil and placed in the freeze for analysis later.

Photo: NOAA

After this we had a meeting with the captain. The PI sets up what samples would be done, where we were going to sample, how we were going to sample – all things science. The captain runs the ship. Their job was to get everyone out and back safely. Their decisions can override the science. We went over safety. Closed toed shoes at all times. When you went through the hatch between wet bay and the working deck on the stern – there was a yellow line lined painted on the deck. No one… NO ONE was to cross that yellow line without a life jacket and hard hat on… NO ONE! And… when the net was being deployed no one… NO ONE was to be aft of the yellow line – PERIOD! Only the crew. There were numerous other safety rules we needed to cover, and we were told we would be doing a sinking vessel drill at some point. These were not different than fire drills you experienced in high school. An alarm would go off – you were to move quickly to your assigned safety station – deploy your survival suit and move to your assigned raft. We would, at some point, practice this. He welcomed us aboard and said we would be getting underway soon.

Phot: NOAA

Later that afternoon, I heard the bell clang, the lines were dropped, and the “O 2” was slowly heading towards the Gulf of Mexico. The adventure, and dream, was beginning. We were now far from the dock when the drill alarm went off. We all scrambled to stations, dawned our survival suits, while the safety officer timed us. We passed. As the sun was setting, and the sky was turning a beautiful orange with purple clouds streaking across, we were heading to sea.

Next… Part 2 – The Deep Blue.

3

3