Your ears are prominently displayed on the sides of your head. But when you look at a fish, you can’t see its ears. That’s because a fish’s ears are located inside its head, right behind each eye. Each ear is a small, hollow space, lined with nerve hairs and containing three otoliths — or ear stones — that gently rest on the nerve hairs.

Otoliths are made of calcium carbonate and grow along with the fish. Every day, fish produce small amounts of calcium carbonate that is layered onto their ear stones. Otoliths grow in circles much like the rings of a tree. Fish use their otoliths to hear sound vibrations moving through the water. The bodies of fish have about the same density as water, so sound passes right through their bodies. Otoliths, however, are much denser than the rest of the fish. When sound vibrations pass through a fish, the differences in vibrations between the dense otoliths and the sensory hair cells is detected by nerves and interpreted by the brain as sound.

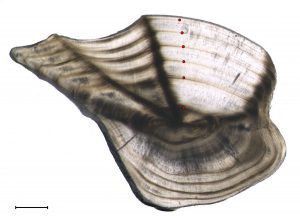

Fish usually have periods of fast growth and periods of slow growth during a year. Faster growth usually occurs during summer months, when more food is available. This difference in growth can be seen on otoliths as wide and narrow zones — wide for fast growth, narrow for slow growth. A fish’s age in years can be determined by counting annuli — or, the number of paired fast and slow growth zones. Annuli look a lot like the layers in a slice of onion. Each annulus (the singular of annuli) typically contains a transparent (fast growth) zone and a cloudy (slow growth) zone.

Otoliths can tell scientists a lot more than just how old a fish is. Multiple records of fish age and corresponding fish length help scientists determine how fast different fish species grow. For instance, using age and length data, scientists know that black drum grow to about 6 inches in their first year, 12 inches in their second year, and 16 inches in their third year. After that they add about 2 inches in length per year. At about 15 years of age, black drum growth slows.

Scientists also use otoliths to follow the migration patterns of fish. They can do this because contained in the otolith layers are rare elements unique to different areas. These elements dissolve in the water at different rates depending on where they are in the world. By looking for these elements in otolith layers, scientists can tell where a fish was at different times in its life.

Scientists can also learn about the diet of fish by looking for otoliths in their guts. They can do this because the otolith of every species of fish looks different. Did you know there is a whole library of otoliths dedicated to helping scientists match otolith to species?

Fun Facts:

- All bony fish have otoliths. Humans also have otoliths, but ours work a bit differently. Sharks and rays, however, do not have them. They rely on other structures for hearing.

- In 2017, Florida’s lead fishery research group, the Fish and Wildlife Research Institute aged 24,524 otoliths (and spines) from 71 different fish species. Where did most of their samples come from? Two-thirds came from fish caught by anglers or commercial fishermen. The other one-third came from research studies.

Can you age a fish? Here is an otolith from a spotted seatrout. Hint: The cloudy middle is called the nucleus. The first year ends at the outer edge of the nucleus. Scroll to bottom for answer.

For more cool fish stories check out:

5

5