This blog post was written by Jonathan Glueckert, a biological scientist with UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants.

This blog post was written by Jonathan Glueckert, a biological scientist with UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants.

Behind every public lake is a team of biologists, natural resource managers, researchers, and decision makers whose job is to manage our freshwater resources. Management decisions are based on data collected by these professionals who use various tools and techniques to monitor aquatic plants in lakes. In this blog, we will explore an aquatic plant biologist’s “toolbox” which helps us collect crucial information for evaluating invasive plant infestations, treatment methods, and adjusting management strategies based on sound science.

An aquatic plant biologist’s toolbox…

Point Intercept Method

To start, point intercept sampling methods are tried and true in the field of aquatic plant management. Biologists set predetermined points at specific coordinates across an area of interest like a whole lake or a cove using GIS so that these points can be navigated to with a GPS and revisited to detect changes in that location over time. Abundance of submersed aquatic vegetation is assessed at each point using modified rakes to pull plants from the lake bottom. The plants are speciated (identified at the species level) and ranked based on the amount of that plant on the rake.

A point intercept grid on Crescent Lake, FL (far left). Modified rake head attached to telescopic pole grabbing hydrilla from a predetermined point (center). Hydrilla sample on a rake head (far right).

Sonar Surveys

On the other hand, sonar surveys, or hydroacoustics, are another method for mapping aquatic plants in lakes. Data can be collected with consumer level sonar devices (depth-finders) mounted to a boat. Boat operators drive transects that comprehensively traverse the water body. Simultaneously, the device records GPS positions and sends acoustic signals or “pings” from a transducer through the canopy of aquatic plants to the bottom of the waterbody. Then, the ping bounces back to the transducer and is logged into a file which can be uploaded and processed by cloud-based software. Plant material and lake bottom can be differentiated by the acoustic signature and the distance between these two signatures are recorded as the plant height. Biologists can use this method to assess biovolume measurements (percentage of the water column occupied by plants), bathymetry (water depth measurements), and lake bottom sediment composition.

Lowrance HDS sonar screenshot showing the lake bottom and clumps of hydrilla (leftt). Biovolume vegetation map of Crescent Lake, FL created by Biobase cloud software. Red is where volume of plants is most dense, blue is minimal vegetation (right).

Satellite Remote Sensing

Now, due to the size of waterbodies and number of public lakes monitored in Florida each year, these tools are often labor intensive. Luckily, technological advancements and availability of free satellite imagery allow us to monitor entire landscapes at the click of a mouse. Images captured by satellites such as the Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission can be viewed on the Earth Observer Browser, are updated regularly, and can be viewed in bandwidths that allow us to see infestations of submersed and floating invasive aquatic vegetation. Viewed over time, this imagery can be used to detect changes in the lake and advise biologists if they need to visit and implement other monitoring techniques or management interventions.

Unoccupied Aerial Vehicles (Drones)

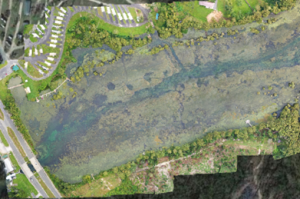

Additionally, aerial imagery captured by unoccupied aerial vehicles, or drones, are also a tool in aquatic plant management and monitoring. With the use of a drone, biologists can map thousands of acres within hours. High resolution imagery is collected and stitched together to create a comprehensive image called an orthomosaic or orthophoto.

For example, Sentinel-2 satellite imagery can be viewed at the landscape level with resolutions around 10 meters per pixel. This results in blurriness as the user zooms in to see more detail. Alternatively, aerial drone imagery can be captured at centimeters per pixel. This allows a biologist to distinguish certain plant species such as hydrilla, water hyacinth, and water lettuce from the air. Locations can be mapped routinely allowing for simple presence and absence surveys or change detection over time.

Sondes and Sensors

Finally, water quality parameters are also used with these other tools to provide a comprehensive understanding of the lake ecosystem. Handheld devices provide rapid assessment of water quality while out on the lake. For long term monitoring, we can use sondes. These instruments house a cluster of sensors that measure pH, temperature, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, and conductivity of the water. They can be left in a lake to continuously log information for the duration of a monitoring period. This data can then be used to track changes in water chemistry.

A handheld pH meter (far left), a sonde underwater (center), and cluster of sensor housed inside of a sonde (right).

In Florida, there are over 8,000 named lakes and ponds that provide endless opportunities for recreational use. Frequent collection of high-quality data is important to inform management decisions on invasive aquatic plant infestations on those waterbodies. Biologists use a combination of these tools to create a comprehensive picture of what is happening on your favorite lakes. In turn, this helps keep them healthy and accessible for a diverse group of stakeholders.

This blog post was written by Jonathan Glueckert, a biological scientist with UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Questions or comments can be sent to the UF/IFAS CAIP communications manager at caip@ifas.ufl.edu. Follow UF/IFAS CAIP on Instagram.

Subscribe for more blogs like this one.

UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Turning Science Into Solutions.

Did you find this post helpful or interesting? Click the heart below!

8

8