Florida is a haven for many forms of insect life, from butterflies and honey bees to termites and fireflies. Unfortunately, its miles of coastline and thriving trade also make it vulnerable to harmful invasive species, which enter our state by highways and seaports and proliferate in our warm, humid climate. The history of Florida agriculture has been a constant struggle against crop-destroying insects and nematodes that eat plant parts and spread disease. Extension has been an important player in that struggle for over 100 years.

Boll Weevils and the Birth of Extension

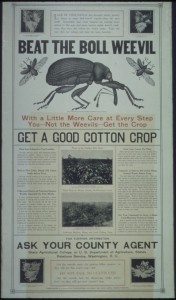

As a matter of fact, it was an invasive insect pest that played a key role in the founding of the nation’s extension service. The boll weevil, a beetle that eats the buds and young bolls of cotton plants, entered south Texas in 1892 and by the turn of the century, it was devastating cotton crops throughout the South. In 1902, the United States Department of Agriculture sent researcher and educator Seaman Knapp to Texas to help find a solution to the boll weevil infestation. Knapp set up an experimental farm to demonstrate to growers how soil cultivation and the use of early-maturing cotton varieties could help lessen boll weevil damage. The farm became the model for agricultural demonstration, and its influence would lead to the creation of the national Cooperative Extension Service in 1914.

In its early years, Florida Extension relied on expertise from the state Agricultural Experiment Station when dealing with insect pests such as corn and sweet potato weevils, aphids of watermelons and citrus, velvet bean caterpillars and bean jessids. In the late 1920s the extension service briefly employed specialists who split their time between plant pathology and entomology, working with growers to control rust mites, whiteflies, scale insects, and Mediterranean fruit fly outbreaks in Florida’s economically sensitive citrus groves. However, after 1931 there would be no full-time entomologists on Extension’s staff for over 25 years.

Extension Entomology Emerges from Its Cocoon

After the Second World War, Florida’s rapid growth and an influx of new pesticides on the market made Extension’s need for entomology advice increasingly critical. Finally, in 1953 James E. Brogdon was appointed the first full-time Extension Entomologist. To help undo the damage caused by insect pests—at that point, worth an estimated $50 million annually—Brogdon worked with growers, industry leaders, researchers and homeowners. He co-created the first insect and plant disease control guide for commercial vegetables in Florida, edited Plant Protection Pointers and the Entomology Newsletter, built the 4-H Entomology project and was a frequent guest on radio and T.V. news programs.

In most cases, insect control efforts are only successful in containing the spread of pests, but on some occasions, they result in complete eradication. In the late 1950s, Extension teamed with the USDA and the Florida Livestock Board to eradicate screwworm, a parasite that had been plaguing Florida’s cattle since the 1930s. In the most concentrated bio-control effort up to that time, USDA scientists bombarded livestock ranches with sterile screwworm flies, while extension agents educated ranchers about how to inspect for screwworms and protect their cattle from possible infection. In 1959, the state of Florida was declared free of screwworm.

In 1965, entomology research, education and extension work converged to form the UF Department of Entomology, adding nematology in 1967.

Chemically Speaking

Throughout the first half of the century, the most common way of dealing with insect pests was to spray them with pesticides. Many of these chemical sprays were naturally derived—sulfur, nicotine from tobacco, pyrethrum from chrysanthemums; some, such as arsenic and cyanide, were highly toxic and their use regulated by the federal government. The use of synthetic chemicals such as DDT became widespread in the 1940s, leading to many questions from growers and food producers about pesticide regulations and toxicity. In 1959, Extension set up the Chemicals Information Center to help keep homeowners and producers up to date on the latest regulations and recommendations for safe handling of pesticides. The Center began printing a weekly newsletter, Chemically Speaking, which is still being published today. In 1962, Rachel Carson’s best-selling book Silent Spring raised public awareness about the dangers of using DDT, and Extension stepped up its information efforts to include pesticide training courses and chemical education groups. When DDT use was banned by the federal government in 1972, Extension responded to the ban with Project Safeguard, a joint program with the EPA and USDA that trained growers in the safe use of toxic pesticides. Today, the Pesticide Information Office on the UF campus provides continuing education for professional applicators who handle restricted use pesticides.

The ABCs of IPM

The trouble with relying on pesticides, besides their potential risks to the environment and human health, is that many pests become resistant to them over time. Beginning in the early 1980s, Florida Extension developed materials about Integrated Pest Management (IPM), a program that emphasizes a varied, broad-based approach to controlling insects and other pests. A huge success with commercial growers and homeowners alike, IPM Florida was developed into a statewide program directed by Dr. Norm Leppla in 2001. Crucial to IPM is accurately identifying and understanding the biology of the insect pests damaging our crops, gardens or lawns. In 1996, Extension partnered with state agencies to develop Featured Creatures, an online resource that provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms, along with recommendations for their management. For more elusive pests, there’s the UF Insect ID Lab, established in 1993, where growers and homeowners can send specimens to be identified by experts.

Once pests are identified and their life cycles and behaviors are understood, a number of control methods become available, such as cultural or biological control. Sometimes the best way to beat a bad bug is with a good bug, and IPM promotes the use of beneficial insects and insect predators. On small farms, a successful IPM program can be complex and multifaceted. To demonstrate how it all works together, in 2010 UF/IFAS Extension established the Living IPM Field Laboratory in Live Oak, Florida. On 330 acres of farmland at the Suwannee Valley Agricultural Extension Center, the laboratory provides hands-on, whole-farm education and training in IPM farmscaping that limits the damage of harmful insects while attracting and supporting beneficial species. The IPM field laboratory is a classic demonstration farm, one that Seaman Knapp would recognize and appreciate from back in the days when crop destroyers like the boll weevil loomed large on the horizon.

May 19-23 is Bug Week at the University of Florida! To learn more, visit http://bugs.ufl.edu

Sources:

Brogdon, J. E. 1967. Extension Entomology: Past, Present and Future. Florida Entomologist, 50:4.

Cooper, J. F. 1976. Dimensions in History: Recounting Florida Cooperative Extension Service Progress, 1909-76. Gainesville: Alpha Delta Chapter, Epsilon Sigma Phi.

Florida Agricultural Extension Service. 1954 Report. Gainesville: University of Florida.

Florida Agricultural Extension Service. 1958 Report. Gainesville: University of Florida.

Florida Agricultural Extension Service. 1960 Report. Gainesville: University of Florida.

0

0