The terms conservation and preservation are used interchangeably, but they actually mean different things. With preservation your goal is to keep the resource in a pristine state – as if humans were not in the picture. This would NOT allow the harvest, or manipulation, of the resource. Wildlife and Estuarine Preserves are places where the natural environment is held in as pristine a state as it was when the land/water was obtained. There are usually a lot of monitoring projects ongoing to see how the system is doing, but no one is allowed to USE the natural resources within.

Conservation, on the other hand, use of the resource IS allowed – but managed. The concept behind conservation of resources is that the resource is not wasted. In many cases, conservation work includes the restoration of resources as well.

The classic story that is taught to all conservation resource management students is The Tragedy of the Commons. In 1833, a British economist (William Forster Lloyd) wrote an essay about the use of the “commons”. The commons, at that time, was a grassy area that could be shared by all ranchers and herders in the village – it was free… the “commons”. It was public and unregulated lands. The locals would bring their herds out to graze and allow them to graze as much as they could. There were no fees and there was the idea that “if I don’t use it… someone else will”. Soon, the grass was gone and there was none to support anyone’s herds. Obviously, the village suffered because of the idea of “I’ll get mine” was very strong within the community. Now they had nothing.

Photo: University of Florida

This concept was echoed by biologist Garrett Hardin in 1968. He pointed out that open use of public owned resources by a small number does not cause real problems. But as the number of “users” increases, and there is no regulation on how much of the resource you can obtain, the resource eventually diminishes, personal lives are harmed, and the overall economy suffers.

Thus, if you are going to USE a public owned natural resource, there is a need to CONSERVE, or MANAGE it. Fisheries is a good example. The red snapper in the Gulf of Mexico belong to no one, or maybe stated – they belong to everyone. It is a public natural resource that is harvested for the benefit of the harvester and the community as a whole (in terms of supporting businesses, etc.) – we all benefit. IF this resource were not managed, the Tragedy of the Commons could occur. The snapper populations could be eliminated, and no one would benefit. So, our marine fisheries are managed… conserved.

Photo: NOAA

There are college degrees in fisheries management and honestly, as you might guess, there is a lot of math involved. We start with the target species… what is everyone interested in harvesting? This can be based on which species are easy to harvest for the harvester – and then good marketing convinces the public they want it. Or it could be the other way around – the public wants it, they are difficult to harvest, but we are going after them anyway. The ole case of supply and demand regulates what is sold at seafood markets, what the price is, and what fisheries managers will focus their time on monitoring and managing.

Most resource managers work for the state or federal government. It has fallen onto them to manage public natural resources. For Florida fisheries, this would be the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) at the federal level, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) at the state level. Here in the Gulf of Mexico, Florida state waters include all estuaries and Gulf waters out to nine miles – this would fall under the management of FWC. Federal waters extend from 9-200 miles out and is managed by NMFS. Numerous commercial and recreational fisheries are managed. These would include snapper, grouper, lobster, crab, shrimp, tuna, swordfish, shark, flounder, and many others.

In order to manage a species, you need to know many things. (1) how many of that species in currently in state or federal waters (stock assessments), (2) are species stocks equally distributed across the Gulf of bay, (3) how long do they live, (mortality rates) (4) how often do they breed, (5) what age do they become sexually mature, (6) how many eggs do they produce (fecundity), (7) how many of those eggs typically reach sexual maturity, and (8) how long does it take to reach sexual maturity. There are many more questions that need to be answered as well, but you can see there is a lot of biology that has to go into resource management.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Then there are the commercial questions. (1) How many fishers (harvesters) are there, (2) are they evenly dispersed across the Gulf or bay, (3) what is their demand, (4) what methods of capture are used, (5) how efficient are these methods, (6) what by-catch (species you do not want) are harvested, and (7) how much of the product is lost between harvest and buyer. Again, there are lot more questions a resource manager would need to know.

Now add in, recreational harvest – those being harvested for fun and family recreation. This group has been on the rise in Florida since the 1950s when affordable Fiberglas boats became available to the public. They certainly outnumber the commercial fishermen and the targets they select and how many they are being removed must be factored into the management plan for any species. And we can’t forget the charter fishing industry.

Bottom line, for some target species (like red snapper) the pressure to harvest is huge. How many fish can be removed from the population and be sustainable (so there are plenty of red snapper next year)? Which group (commercial, recreational, charter) gets how many? How do we manage a common area so that we do not have a tragedy?

Enter… the Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY).

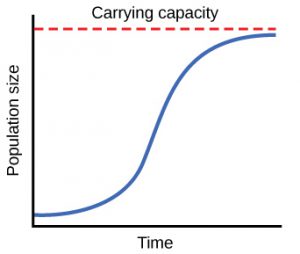

The maximum number of individuals that can be removed from the population and be sustainable. For many fisheries plans – this is around 30% of the population, but certainly varies with species and location. Much of the information mentioned above is needed to work this model.

Image: Georgia Tech University

The model has a few assumptions. It assumes that all populations produce enough offspring to replace the older members who are lost (remember, most offspring do not survive more than a year). It also assumes that growth, survival, and reproduction rates increase when there is stress on the population. The third assumption is that all populations reach a maximum number with which the space and food resources can support – the carry capacity. Calculating the MSY for any one species can be complicated. I suggest anyone interested in this process read more. Also, note that many in the resource manager realm are not completely sold on the idea of the MSY as the base of the management plan. Not only are the questions about some of the assumptions, but it does not factor in other non-target species captured (by-catch).

Either way, managing the commons is not an easy job.

When receiving their quotas for the year from a state or federal agency, most fishermen feel they have been “robbed” and that the science is not “good”. In some cases, there may be issues, such as assumption stock sizes of red snapper are equal throughout the Gulf and that a “one size fits all” management plan is unrealistic.

Photo: Dr. Andrew Coleman

In these examples we have focused on the fishery resources. However, there are mineral resources, habitat use, and even amount of tourism in marine environments that have needed management in recent years. Also, in 1973, the Endangered Species Act was passed which required management for listed species. Most of these fall under the federal resource managers but there are state listed species as well. And in some cases, the federal government has turned over management of some to the states.

Photo: FDEP

With the idea of sustaining these resources, restoration has now entered the realm of resource management. There are many programs that work in this area. Fisheries restoration can be performed within hatcheries. We general think of aquaculture as an industry which produces food species, but there are projects that culture and release population stressed marine species in hopes of building the stocks. There are numerous efforts in restoring habitats such as living shorelines (marshes), seagrasses, and corals. Many of these are produced in aquaculture projects and then planted by volunteers or NGOs.

There are also resource enhancement projects as well. Artificial reefs are not really considered restoration because it is a habitat (resource) that was not initially there. However, there is evidence of resource enhancement provided by them. There are also living shoreline projects that have been used as much, if not more, as enhancement as restoration.

There are a lot of efforts across the country to manage, restore, or enhance our marine resources. You should learn about some in your local area and, if possible, get involve with some.

ACTIVITIES

- Estimating populations. One method of estimating a population is by mark and recapture. In this method the manager captures a number of individuals from the population (M). They mark them is some fashion (band on foot, electronic tag, “ear-ring”, ribbon tag on fin). Sometime later, let’s say a month, they use the same method and recapture a number (C). Within this group you count how many were tagged initially (R). From this we can estimate the population using the following

N = (M*C)/R

(N) would be the estimated population. To practice this, you will need the following:

– brown paper bag

– one bag of brown (dark) dry beans

– one bag of white (light) dry beans

Pour a handful or so of the light beans into the paper bag. This represents your existing population.

Remove 20 of the light beans and replace with 20 of the dark beans. (If you do not have 20 beans from your original group remove 10% of what you have). These represent the number of captured and tagged animals from your tagging project (M).

Shake the bag a few times to mix them.

Now remove a handful of beans – your second capture. How many beans did you capture? (C)

How many of these were dark beans? (R)

Use the model to estimate your population (N = (M*C)/R

NOW actually count how many beans in the population – remove ALL beans and count.

How close was your estimate to the real population?

Calculate your percent error

% Error = (true value – estimated value) / true value

What was your % error?

NOW remove 20 more light beans (or the same number you did before) and replace with dark beans (NEWLY marked species).

Shake the bag and repeat the calculations.

Was your estimate closer this time?

Was your percent error lower?

What does this tell you about Mark-Recapture efforts for estimating populations?

- Field Trip. Weeks Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve.

Visit this National Estuarine Preserve in Alabama near Fairhope and Pensacola Florida to see what they look like and how they work. If you are not in the area, find a wildlife preserve, refuge, or estuarine preserve near you.

Weeks Bay NERR – 11300 U.S. Highway 98, Fairhope AL 36532.

- Field Trip. Seafood Market. What are they selling? What are their most popular items? What do they not sell a lot of that they think people should consider buying?

4. Field Trip. Visit a living shorelines project near you and see how it is laid out. If you are not sure where these are, contact Rick O’Connor roc1@ufl.edu who can help.

0

0