Iris Strzyzewski and Joe Funderburk, North Florida Research and Education Center, University of Florida

The U.S. supplies 29% of the total production of strawberries, making it the largest producer worldwide. Florida harvests about 10,000 acres annually valued at $400 million, ranking second only to California. Flower thrips are pests of numerous fruit and vegetable crops, feeding and laying eggs in the flowers and fruit causing quality reduction and yield losses. Several species of thrips occur in Florida strawberries including the western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis), and Florida thrips (F. bispinosa), that occur statewide, and eastern flower thrips (F. tritici) that occurs in northern Florida. These thrips have been implicated in bronzing and cat-facing injuries to strawberry in Florida (Figure 1).

Strawberry growers have become increasingly concerned about flower thrips, and they have responded by increased insecticide applications. Yet, the relationships between numbers of different thrips species, injury to fruit, and yield loss have not been determined. Researchers at the University of Florida are conducting experiments to address these gaps in knowledge. They are characterizing the injury caused by each thrips species to strawberry fruit, and quanitfyuing the relationships between thrips populations and injury. The goal is to develop economic thresholds for management programs,to target insecticide use that is the most cost effective.

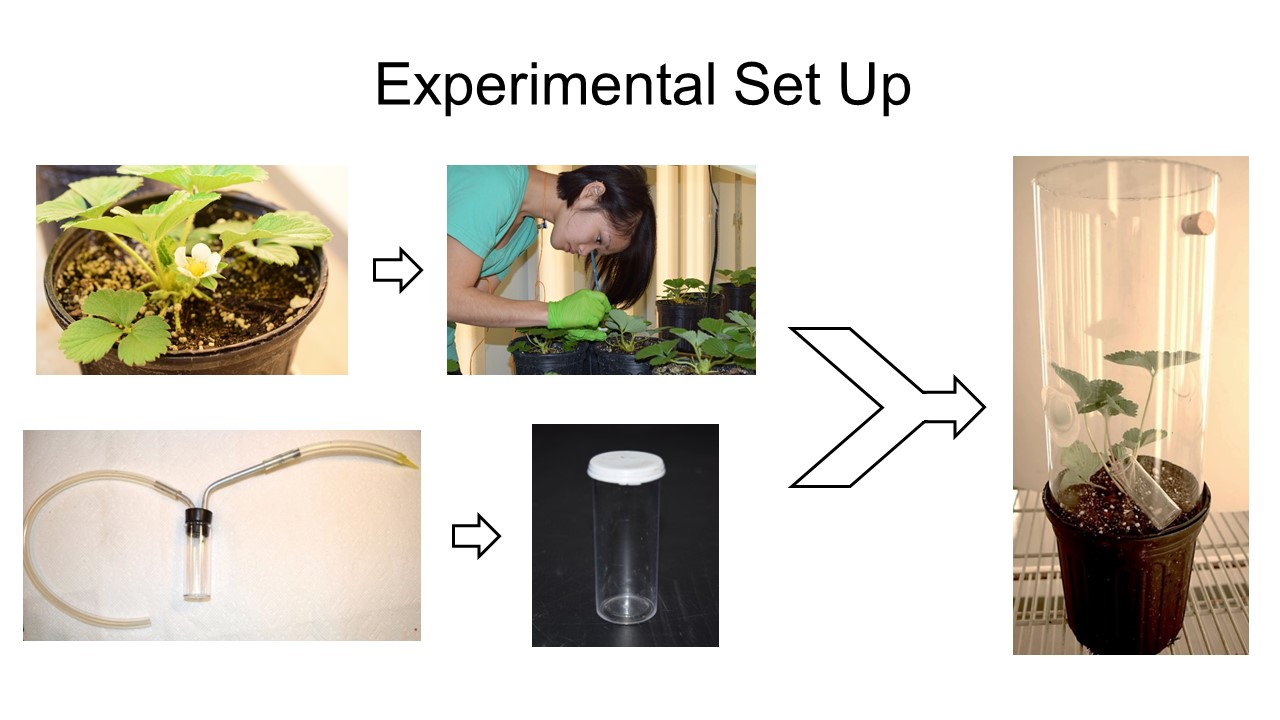

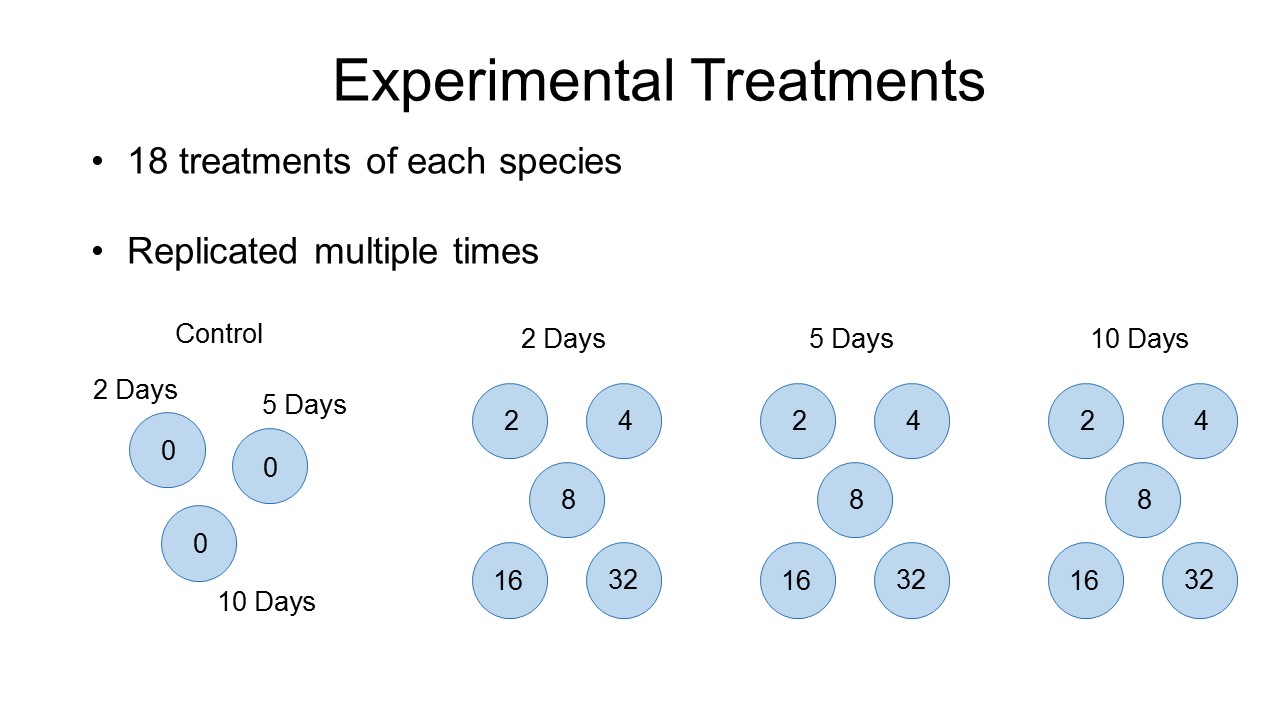

In laboratory experiments, thrips were introduced onto ‘Festival’ strawberry plants with a single flower that had been hand pollinated. Densities of 2, 4, 8, 16, or 32 adult thrips of individual species were introduced onto plants caged under thrips-proof cages for a duration of 2, 5, or 10 days. These procedures are illustrated in Figure 2. The treatments are illustrated in Figure 3. The fruit were allowed to grow until ripe, which was about 21 days. Once ripe, the fruit was assessed for the presence of thrips-inflicted injury. Namely, fruits were weighed, and the diameter was measured. Any surface injury (cat-facing and bronzing) was quantified.

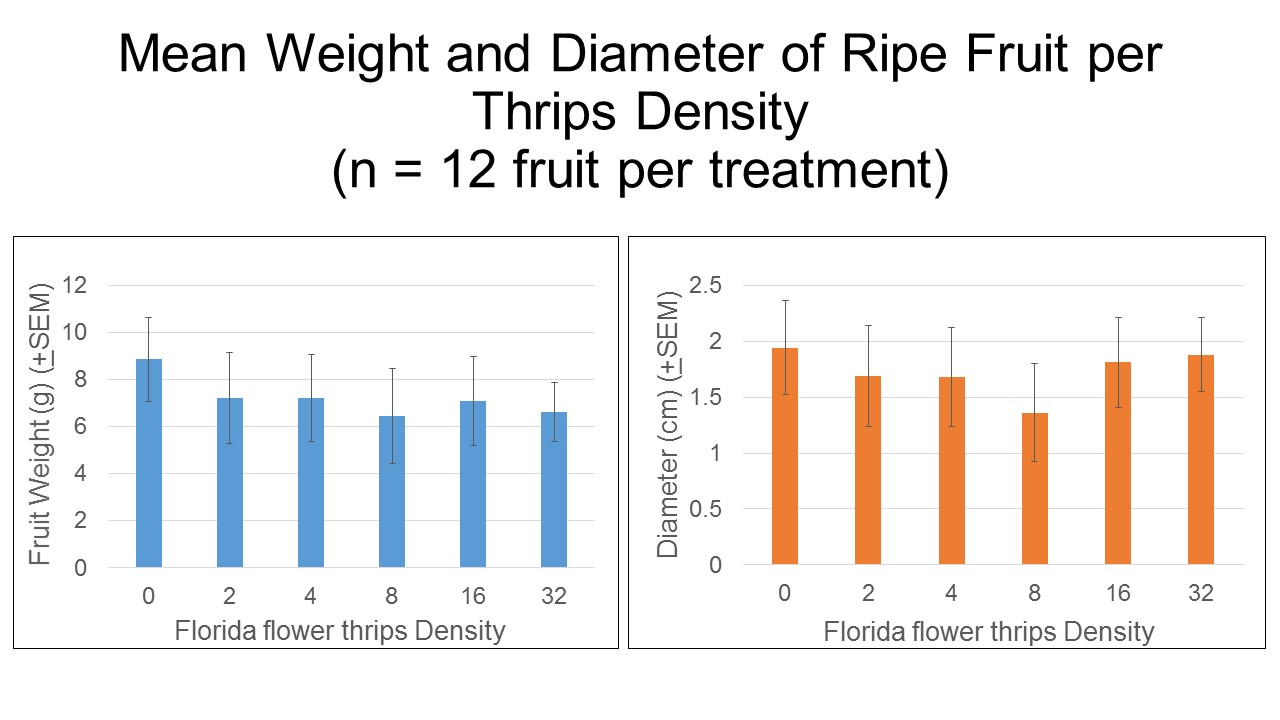

Currently, more data has been collected on Florida flower thrips than for western flower thrips and eastern flower thrips. So far, there were no significant differences in the mean fresh weight, or mean diameter of fruits from the treatment groups when compared to the control, although there may be a trend with fresh weight between the control group and the thrips treatment groups (Figure 4).

There was no bronzing observed on the fruits. As with fresh weights there was a trend between the control group and the thrips treatment groups in the amount of cat-facing, but this also was not significant. At this point, we are in the process of conducting more replications, and the results so far are not conclusive. However, it is obvious that strawberries can tolerate thrips feeding to some degree on the flowers and fruits before growers will experience significant damage. There appears to be little injury to strawberry even at the very high densities of 16 and 32 thrips per flower. These laboratory experiments are being supplemented with field trials relating thrips abundance to fruit yield and quality. Data from this research should allow for the development of economic thresholds of thrips populations for strawberries in the near future.

For more information on thrips in strawberries and the insecticides labeled for their control, download:

Thrips in Florida Strawberry Crops

0

0