- Catch and release practices can help conserve fish populations but they do not guarantee the fish will survive, as handling and air exposure can have negative health impacts and cause mortality

- Scientists have developed a new fishhook design that allows anglers to catch and release fish in the water without handling them or exposing them to air

- A new study shows these bite-shortened hooks are just as effective as standard hooks at landing fish

Scientists in Florida have developed and tested a new kind of fishhook designed to improve fish survival and support sustainable recreational fishing.

Researchers with the University of Florida, U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have published their findings in the journal “Fisheries,” where they show that a modified version of a standard fishing hook allows anglers to catch and release fish successfully and without any direct contact with the angler.

Handling fish and exposing them to air can cause “discard mortality,” which is when fish die after they are caught and released, said Holden Harris, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at the UF/IFAS Nature Coast Biological Station.

“Catch and release can help conserve fish populations, but it doesn’t ensure fish will survive after you let them go,” Harris said. “Handling a fish and exposing it to air can injure an already exhausted animal. That makes them more vulnerable to predators after they are released. Handling the fish with nets and hands also disrupts the mucus membrane covering their bodies, which exposes fish to infection.”

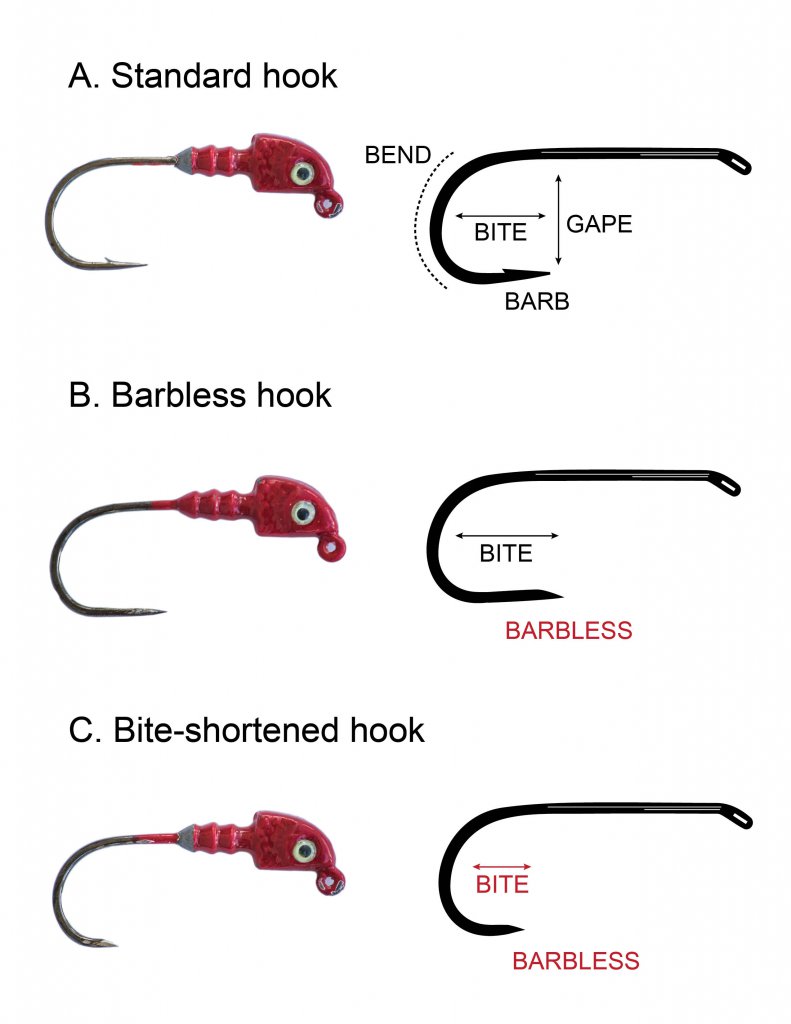

In their study, the researchers tested a “bite-shortened” hook, a standard barbless fishing hook modified to have a shorter point or “bite.” The bite-shortened hooks can be made easily with simple tools.

Earlier field trials with bonefish on Palmyra Atoll conducted by one of the study’s co-authors, Andrew Gude, manager of the Lower Suwannee and Cedar Keys National Wildlife Refuge, found fish would “spit out” bite-shortened hooks once they were reeled in toward the angler and the angler gave slack in the fishing line.

The idea appeared promising and prompted the researchers at the UF/IFAS Nature Coast Biological Station to begin more rigorous testing.

“In this study, we wanted to test the hooks systematically to see how they performed compared to other hook types for their ability to successfully stay hooked in the fish during the reel-in and then self-release from the fish once it was landed boatside,” Harris said.

Working off the coast of Cedar Key, Florida, the researchers tested three kinds of hooks: barbless, barbed, and bite-shortened. For the purposes of the study, they targeted spotted seatrout, a popular coastal sport fish.

They found that compared to the other hooks, bite-shortened hooks were just as successful at landing fish. However, bite-shortened hooks made it significantly easier for anglers to release fish without directly handling them.

“We look at this as a new kind of fishing that might hold appeal for conservation-minded anglers who are concerned about discard mortality,” said Mike Allen, senior author of the study and the director of the UF/IFAS NCBS. A hook like this could ultimately allow fishing in areas where minimizing impacts to fish stocks is a high priority, he said.

While it is still too early to say what the environmental impact of these new hooks might be, Harris said he hopes this first study will inspire other researchers to keep testing the hook design and gather more data.

“It would be great to know how these hooks perform with different fish species, different fishing techniques and in the hands of different anglers,” Harris said.

In the meantime, curious anglers can make their own bite-shortened hooks and try them out on the water. Harris and his co-authors have produced a video demonstrating how to turn a standard barbless hook into a bite-shorted hook using tools found at the hardware store.

2

2