- Norovirus is responsible for millions of cases of food poisoning each year. New evidence suggests the common bug alters the bacteria that live in our gut.

- These findings shed light on the connection between the gut microbiome and overall human health.

- Future research will explore whether changes to bacteria help or hinder norovirus’s infectiousness.

Norovirus is a food-borne virus that causes food poisoning in millions of people each year. A new study from the University of Florida shows this virus also alters the bacteria that live in our gut, providing new clues about the human microbiome’s role in our health.

“A lot of research has shown that intestinal viruses use gut bacteria to increase their infectiousness. However, no one has looked at what happens to the bacteria themselves during this process, which is what we investigated in this study,” said Melissa Jones, senior author of the study and an assistant professor in the UF/IFAS department of microbiology and cell science.

The researchers observed this virus-bacteria interaction in two ways: They introduce human norovirus to common human gut bacteria strains in a controlled lab environment; and they infected mice with the mouse version of norovirus and analyzed the bacteria in the droppings.

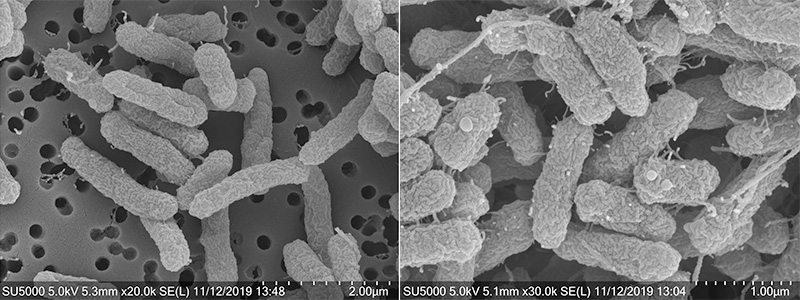

The researchers found that in both scenarios, gut bacteria experienced changes in gene expression —which genes are turned on or off. They also saw the bacteria’s surface became wrinkled and sprouted new webby appendages. It is not yet clear how long these changes last. Following these changes, the microbes increased their production of outer membrane vesicles, nano-sized packets of molecules bacteria use to communicate with each other and with human cells, Jones explained.

However, the message contained in these vesicles is still a mystery. They may help gut bacteria and the human body better respond to the virus to stop infection. Or, they could be part of a stress response in bacteria that helps norovirus cause further disruption in our gut.

If the latter is true, it may help explain why norovirus in particular is so good at infecting people, Jones said.

“Norovirus has been called the perfect human pathogen because it gets in the body, usually through contaminated food, and makes lots and lots of copies of itself under the radar of our immune system. Then, as anyone who has gotten norovirus knows all too well, it spreads itself widely to other people through all the bodily fluids we lose while sick,” Jones said. “Our future research may show how gut bacteria are part of this very efficient process.”

In the meantime, scientific and public interest in the gut microbiome continues to grow. Recent research points to connections between the microbiome and nutrient absorption, immunity, mental health and more.

The impact of viruses on gut bacteria is yet one more piece in that larger, complex puzzle, Jones said.

The study’s authors include co-first authors Chanel Mosby-Haundrup and Sutonuka Bhar, who are pursuing doctorates in microbiology and cell science from the UF/IFAS College of Agricultural and Life Sciences; Matthew Phillips, a postdoctoral associate in the UF College of Medicine’s department of molecular genetics and microbiology; and Mariola Edelmann, assistant professor in the UF/IFAS department of microbiology and cell science.

The study is published in “Journal of Extracellular Vesicles.”

0

0