Where there’s smoke, there’s fire — and also lots of microorganisms, according to a new study from the University of Florida.

For the first time, researchers have measured the number of microbes in smoke from fires in wilderness areas, also known as wildland fires. The researchers also found that a surprisingly high percentage of microbes survive the blazes and are lofted into the air.

Smoke analyzed for the study contained five times more microbes than smoke-free air, said Rachel Moore, a UF/IFAS College of Agricultural and Life Sciences graduate who led the study as part of her doctoral work.

The researchers also found that the percentage of microbes still alive in the smoke was the same as that found in ambient air.

“When you look at the smoke particles under a microscope, it’s as if the particles are life rafts for the microbes,” said Moore, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at Georgia Tech University. “Just how many microbes there were and how many were viable was a big surprise.”

Brent Christner, Moore’s dissertation advisor and one of the authors of the study, said he was also surprised, but for an additional reason.

“Common sense would tell you that fire would just kill and incinerate microbes when it burns through vegetation, but our findings show that’s not the case,” said Christner, an associate professor in the UF/IFAS department of microbiology and cell science.

While smoke poses a health risk to people, the microbes identified in the study aren’t harmful to humans on their own.

“The microbes released in these fires are similar to the kinds that live on plants. The results of this study indicate that fires may be an important way for these organisms to distribute in the environment, which is of ecological interest,” Christner said.

How microbes survive wildland fires is still unclear.

“The processes that aerosolize microbes during combustion of vegetation are clearly not as destructive as they’ve been presumed to be,” Christner said.

For the study, researchers analyzed smoke sampled during eight prescribed fires at the UF/IFAS Ordway-Swisher Biological Station, located about 20 miles east of the university’s main campus in Gainesville. With thousands of acres of wilderness, the station is a living outdoor laboratory where scientists can do experiments in the natural environment.

During each fire, Moore set up instruments called volumetric samplers downwind from the blaze. These machines sucked air and smoke from the fire through special filters that trapped the particles.

“Think of the filter on your vacuum cleaner that traps dust. These machines are essentially powerful vacuums with very fine filters that catch particles as small as 1 micrometer,” Christner said. For context, the width of a human hair is about 75 micrometers.

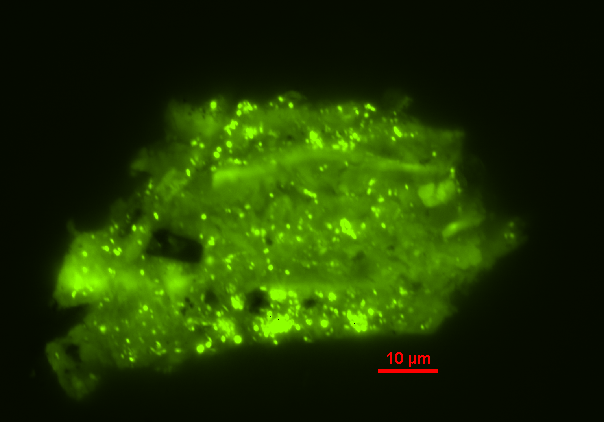

After sampling, Moore took the filters back to the lab, where she used various lab techniques to remove the particles from the filters and calculate the total number of microbes in the sample. She also used a special staining technique that makes living microbes appear green under the microscope, allowing her to estimate the percentage of viable organisms.

Moore and Christner also wanted to know if burning dead vegetation emitted more microbes than living vegetation. To find out, they teamed up with scientists at the Idaho Fire Initiative for Research and Education at the University of Idaho, who burned samples sent from Florida on a specially designed laboratory burn table. The researchers found that smoke from dead vegetation contained more microbes than smoke from living vegetation.

The study’s authors note that the prescribed fire used in the experiment was far smaller and less intense than the massive wildfires that have burned millions of acres in the Western United States. over the last few months.

“We think the huge fires out West are emitting even more microbes than what we found in our experiments,” Moore said.

The study is published in “The International Society for Microbial Ecology Journal.”

0

0