Welcome to July in southeast Florida. It’s hot. As in, really hot. Has this summer been hotter than usual? The answer is yes. What is of particular concern is that this heat wave has arrived relatively early in the summer and is being felt around the world. When we feel the heat, we can go inside and sit in the comfort of air-conditioning, whether at home or a public space such as a library. The elevated air temperature translates into warmer water temperatures. For creatures that live in bodies of water, especially closed or shallow-water systems, there is no escape. This spells trouble for fish and other bottom-dwelling organisms such as stony corals.

Why are we experiencing this heat wave?

The answer lies in El Niño, a climate phenomenon that brings warmer ocean temperatures. 2023 has developed into an El Niño year (its sister effect, La Niña, brings cooler temperatures and drier conditions). El Niño and La Niña are naturally occurring, however, El Niño years are becoming more severe as increased greenhouse gas emissions raise the global temperature.

What does this mean?

In addition to our feeling the heat and being vulnerable to heat-related illnesses (dehydration, heat exhaustion, heat stroke), the heat is raising water temperatures as well. North Biscayne Bay is averaging more than 86 degrees Fahrenheit in some spots (These data are publicly available, gathered from Florida International University’s research buoys and capture information in real time). This temperature is higher than normal for this time of the summer. Since Biscayne Bay is a shallow, largely enclosed aquatic system, this elevation in temperature can mean increased algal production, less available dissolved oxygen in the water, and potential fish kills.

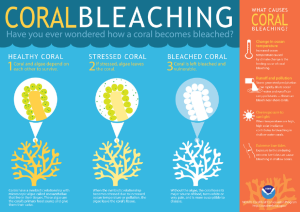

Offshore on Florida’s Coral Reef, water temperatures at depth are averaging 87-88 degrees Fahrenheit. Stony corals that build the reef require clear, warm water to survive, but the sustained temperatures of 86-88 degrees are too warm. Corals are living animals that host photosynthetic algae, zooxanthellae in their tissues. These zooxanthellae convert sunlight into energy and nutrition for the corals and provide the corals with their various color patterns. However, when the water temperatures become too cold or too warm for a prolonged amount of time, the zooxanthellae leave the corals. What’s left behind is the clear coral polyp, and the white skeleton beneath the tissue. The white skeleton is what led to the common term of “bleaching” (Braverman 2016, Hoegh-Guldberg 1999, Lohr & Patterson 2016). Bleaching is a natural occurrence, and every year, some corals throughout Florida’s Coral Reef will bleach.

Graphic: NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program

Coral bleaching isn’t necessarily fatal, but since the zooxanthellae are not present, the coral is essentially starving and in an extremely weakened state. This state also leaves corals more susceptible to other stressors, such as disease. Corals can recover from bleaching if the conditions change (in this case, the water temperatures cool). Normally, coral bleaching is observed in late August or early September when water temperatures are at their peak. There have already been observations of coral bleaching on Florida’s Coral Reef, and it is only mid-July. If the current weather patterns continue, it is likely that negative impacts will be observed both within Biscayne Bay and offshore on the reef.

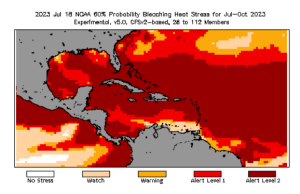

NOAA’s coral outlook

The scientific community will continue monitoring sea surface temperatures and coral bleaching and will

update the NOAA Coral Reef Watch website. The site uses satellite imagery and models to create predictions of bleaching activity.

Scale:

• No stress

• Watch: Conditions might accumulate stress

• Warning: Bleaching possible

• Alert 1: Significant bleaching expected

• Alert 2: Significant mortality likely

Map: NOAA Coral Watch

What can you do?

As water hugs all of Miami-Dade County’s coast, it’s imperative to enlist the assistance of anyone who spends time on or in the water. Marine disturbances including pollution, algal blooms, fish kills, boat groundings, anchor damage, or coral disease can be reported to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s SEAFAN program: www.SEAFAN.net.

If any algal blooms or fish kills are observed, please report them to Miami Waterkeeper: hello@miamiwaterkeeper.org.

Coral bleaching may be reported to: SEAFAN BleachWatch.

If you are interested in learning how to identify and report coral bleaching, please contact me: azangroniz@ufl.edu.

References:

Braverman, I. 2016. Bleached! Managing coral catastrophe. Futures: 92, p. 12-28.

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. 1999. Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. Marine and Freshwater Research 50(8), p. 839-866

Lohr, K., Patterson, J. 2016. Coral reef conservation strategies for everyone. University of Florida Electronic Data Information Source. 7pp. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FA199

1

1