Basic coral biology

Corals are incredible animals that build reefs in the ocean. While they might look like rocks, they are living organisms that require certain conditions in which to live: clean, clear water, warm water, the right amount of nutrients and the and the right amount of wave action. Changes to any or a combination of these conditions can cause stress for corals.

One thing that makes corals particularly unique is their symbiotic relationship with a microscopic algae that lives in their tissues. This algae is called zooxanthellae. The zooxanthellae photosynthesize and provide corals with 85-90% of their food and nutrition for survival. In turn, the corals provide a safe home for the zooxanthellae. The corals themselves display in a multitude of colors and get their coloration from the zooxanthellae.

What is bleaching?

“Bleaching” is a colloquial term given to when corals appear white. When the corals become stressed, they respond by expelling their zooxanthellae. Without the zooxanthellae to give the corals their color, their tissue is clear and one can see through that tissue to their white skeletons.

Bleaching is a response to stress. In the great majority of cases, this is thermally-induced stress. While there was a prolonged cold snap in January of 2010 that prompted a bleaching event, more often than not, bleaching occurs in the late summer months when ocean temperatures are warmest. With climate change causing rising sea surface temperatures, warm-water bleaching will likely be more frequent.

Does bleaching kill corals?

Bleaching itself does not directly lead to coral mortality. However, since the coral animal is without its major source of nutrition, it remains in a severely weakened state, similar to a person who is ill and in the Intensive Care Unit. The corals’ overall health is compromised, leaving it more susceptible to other stressors (disease, poor water quality, turbidity, etc.). The good news is that corals are in fact able to recover from bleaching, if the stressor is reduced or conditions return to normal quickly enough. In fact, major environmental disturbances (i.e., hurricanes) can actually help corals recover by stirring up the water, and bringing deeper, cooler water closer to shore to provide a bit of relief.

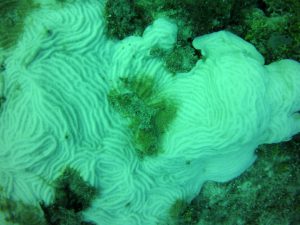

My colleague at Crystal Clear Vieques in Vieques, Puerto Rico monitored a Grooved Brain coral (Diploria labrynthiformis) over time, documenting its bleaching and recovery.

Photos: Sarah Elise Fields/Crystal Clear Vieques

What you can do:

Florida’s Coral Reef runs more than 300 miles long which makes it challenging to know just what’s happening in every part of the reef. Divers and snorkelers can help by reporting observations of bleaching (and photos) to: www.SEAFAN.net.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s SEAFAN Bleach Watch program, visit here: https://floridadep.gov/rcp/coral/content/bleachwatch.

You can also help lower your environmental footprint by conserving water and promoting Florida Friendly Landscaping principles in your work or home landscape.

0

0