When we talk about insect conservation, the conversation usually centers on “saving the bees.” But this often overlooks an entire world of tiny, unseen creatures that are just as vital to our ecosystems. These small, often overlooked arthropods, like predatory mites, parasitoid wasps, and many others, are quietly working behind the scenes. I want to take you on a journey under the microscope to meet just a few of these unsung heroes.

Why I’m Obsessed With the Tiny Stuff

Before we dive into these microscopic marvels, let me share how I developed an obsession with microscopy over the years. I was fortunate to work in labs with high-tech microscopes and in environments that encouraged curiosity. I also had the unique experience of pursuing a doctoral degree program that was broad in scope yet flexible enough to cater to individual interests.

As a result, I could happily spend my life staring into a microscope, discovering all the hidden details of the micro-world. I carry a hand lens with me everywhere I go because there’s always something new to notice.

For the longest time, I thought this fascination was mine alone—or at least shared with only a few people in my career field. But when I started sharing my observations with others, I realized how many people are just as captivated as I am. That realization sparked a drive in me to share these tiny, fascinating creatures with everyone who doesn’t get the privilege to see them (and I truly view it as a privilege).

I’ve always loved nature documentaries and wildlife conservation, but my niche is the “little guys” because they don’t get nearly enough recognition—and I want to change that.

Pollinators: It’s Not Just About the Bees

When we think about insect conservation and the ecosystem services that insects provide, pollination is often the first thing that comes to mind. And when we talk about pollinators, bees usually steal the spotlight. While I admit, they are iconic, easily seen, and essential. But the pollination story is so much bigger than just bees.

A wide variety of insects, arthropods, and even vertebrates all play a role in keeping our ecosystems thriving. Bees, flies, beetles, butterflies, moths, wasps, hummingbirds, bats, and even humans—all contribute to pollination in their own way, whether as primary pollinators or more incidental, secondary pollinators.

The point is that pollination is a team effort, and every species matters, whether it’s the well-known honey bee or an almost invisible fig wasp.

Pollination Isn’t Their Only Job

Insects and other arthropods provide many ecosystem services beyond pollination, including:

-

Predators – Hunt and consume pests (e.g., lady beetles eating aphids).

-

Parasitoids – Lay eggs in hosts, killing them from the inside (e.g., Aphidius wasps targeting aphids).

-

Decomposers – Break down organic matter (e.g., isopods recycling dead leaves).

-

Food sources – Serve as meals for other wildlife (e.g., caterpillars feeding birds).

-

Producers – Create useful products (e.g., honey, silk, dyes and more).

Predators and parasitoids are my favorites because they keep pests in check—and they do it in a totally awesome way.

Wasps Deserve Some Respect

Wasps get a bad rap. Everyone loves bees, but wasps? Not so much. Here’s the thing:

-

Many wasps also pollinate.

-

They are some of our most important biological control agents.

-

Some are big and showy, like yellow jackets, but many are so small you’d never notice them. Some species are the size of a grain of salt!

If you take nothing else from this blog, let it be this: wasps aren’t villains—they’re heroes.

Tiny Wasps vs. Aphids:

Aphids reproduce incredibly fast thanks to parthenogenesis (they don’t need to mate) and viviparity (live births). But tiny parasitoid wasps keep them in check. These wasps inject their egg into the aphid, and the developing larva slowly consumes the aphid from the inside out. Brutal, but effective.

The World of Galling Wasps

If you ask me what my favorite wasps are, I’m going to tell you it’s the galling wasps, most of which belong to the family Cynipidae. These tiny insects have evolved a remarkable ability: they can trigger plants to grow strange, sometimes beautiful structures called galls. These galls serve as protective nurseries for their larvae, offering both shelter and food.

These galls come in all sorts of forms—round, fuzzy, spiky, even resembling flowers. And while the wasps themselves are barely visible to the naked eye, the galls they leave behind often remain on plants long after the adult has emerged. Because the gall tissue is part of the plant, it sticks around and becomes its own little microhabitat. Other insects, mites, fungi, and microorganisms move in, transforming that gall into a tiny ecosystem.

Oak stem gall formed by gall-inducing wasps. Photo credit: James Castner, UF.

Mosquitoes: The Love-Hate Relationship

Even insects we’re not particularly fond of—like mosquitoes—deserve a little recognition. I’m guilty of forgetting this myself. As I write this, I have a few itchy welts I’m trying (and failing) not to scratch.

But here’s the thing: mosquitoes play roles in ecosystems that we don’t always appreciate. They’re a key food source for many creatures—fish, frogs, dragonflies, bats, birds, and countless others. If I had the power to eliminate every mosquito overnight, I’d be tempted. But ultimately, I wouldn’t do it. Removing mosquitoes completely would have ripple effects on food webs and could unintentionally harm other species that rely on them.

That said, I’m not suggesting we start a mosquito fan club. But I do support research and efforts that aim to balance insect conservation with human health and well-being—because mosquitoes also pose serious health risks, spreading diseases that affect humans, pets, and wildlife. We can’t ignore that reality.

And here’s something surprising: not all mosquitoes are created equal. Did you know there’s a mosquito that eats other mosquitoes? Meet the elephant mosquito (Toxorhynchites spp.). Unlike the bloodsuckers we all know, adult elephant mosquitoes feed on nectar and plant juices, and their larvae are fierce predators of other mosquito larvae (among other aquatic invertebrates), including those of disease-carrying species like Aedes aegypti.

Check out UF resources on mosquitoes here.

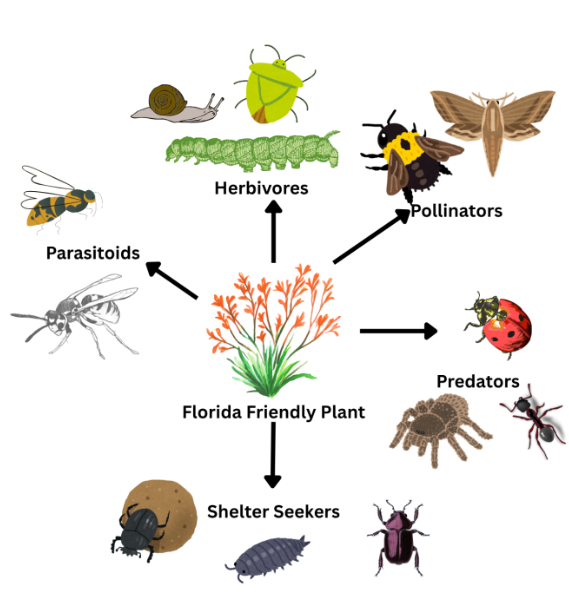

One Plant = Hundreds of Connections

Adding just one Florida-friendly or native plant to your yard can dramatically boost diversity. Why?

-

One plant supports dozens of herbivores.

-

Those herbivores attract predators and parasitoids.

-

Some parasitoids even have their own parasitoids (hyperparasitoids!).

Biodiversity builds on itself—it’s not linear, it’s exponential.

Get Curious About the Little Things

I have spent a couple of years obsessing over the little things, and I have many more years of obsession and learning ahead of me. One thing that excites me is knowing that even if I dedicate the rest of my life to this, there will still be so much more to learn.

That said, I’m not asking everyone to reach my level of fanaticism. You don’t need to know everything you’re looking at—it’s the curiosity itself that matters. All I ask is for more people to take a moment to go outside and really look at the tiny details in your plants. A simple hand lens can open up a whole new world of interactions happening right under your nose.

Food for thought: Microscopes are more affordable than you might think. A good beginner stereo scope can cost less than a nice dinner out (around $15–$50), and it may even change the way you see the world.

Want to See More?

If this blog sparked your curiosity, I included some of this information in a short 15-minute presentation on this topic. Watch it on the Manatee County YouTube page here.

This was part of a collaborative webinar project with other agents in our district. If you’re interested in insect conservation, pollinator gardens, Florida-friendly plants, or hearing more about the Great Florida Pollinator Census coming up August 22–23, check out the full webinar recording here.

2

2