Summer can be a time of fun and fellowship. Everyone who lives in Florida knows it gets very hot during the summer. We have come to expect June, July and August to be hot and humid. Just as heat can affect humans it can affect cattle. Heat stress on cattle doesn’t just make them hot and uncomfortable, but it can also cost cattle producers millions of dollars each year.

Heat stress is caused by high ambient temperatures and high relative humidity. Cattle may begin feeling heat stress as the temperatures rise above 75°- 80º F with relative humidity over 50%. The optimal temperature for cattle is between 50° and 75° F. This comfort zone will vary for cattle depending on their body condition, hair length, level of nutrition, health, breed, color of hide, age and acclimation to their environment. Access to cool, clean water and shade helps keep the animals body temperature within normal limits. It is estimated that water consumption can increase about 2.5 times as temperature increases. With the increase in water consumption there is an increase in urination which depletes the body of minerals such as salt, potassium, and magnesium, just as in humans. To help with the loss of these minerals it is recommended to provide free choice trace minerals.

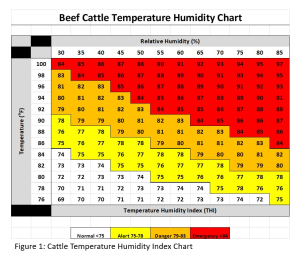

There are different levels of heat stress in cattle. These levels are based on the temperature humidity index (THI). The THI is calculated by the ambient air temperature and the relative humidity percentage. A dangerous level is indicated by an index value of 79 or greater. For example, on May 23, 2023, the temperature was 88° F with a relative humidity of 65% with a THI of 82. This would be considered a dangerous level, as are most summer days in Florida, and precautions should be taken.

Source: https://beef.unl.edu/beefwatch/heat-stress-handling-cattle-through-high-heat-humidity-indexes

Source: https://beef.unl.edu/beefwatch/heat-stress-handling-cattle-through-high-heat-humidity-indexes

The THI is a guide to determining heat stress. Heat stress on high producing cows typically begins at THI levels above 75. When THI levels exceed 80, severe heat stress on pasture cattle begins and shade and clean water sources are essential. Indexes above 85 can result in fatal heat stress. Cattle will exhibit signs of heat stress at differing levels depending on their individual make up as mentioned above. Some signs of stress include crowding under shade or trees or in ponds or around water troughs. Cattle may also begin to salivate more and exhibit open-mouthed or rapid breathing. Traditionally stress levels can be determined by the breathing levels. For moderate stress the cow will take 80-120 breaths per minute, increased or strong stress levels would be 120-160 breaths per minute and may include panting or open mouth breathing, and severe stress would be over 160 breaths per minute with open mouth panting and protruding tongue. As cattle begin to feel the heat stress you may notice a decrease in their appetite. The further their appetite decreases the more they must utilize their stored energy. This can lead to a decrease in body condition, rate of gain and milk production. Heat stress has also been shown to decrease breeding efficiency. Often times you will notice a decrease in the cycling of cattle and reduced conception rates. In extremely severe cases heat stress can cause death.

There are numerous ways to reduce heat stress on cattle. Since we don’t feel the heat the way cattle do, planning for ways to reduce stress must begin early. One way to reduce heat stress is to provide enough shade for the number of cattle on the pasture. It is recommended to have 40-60 square feet of shade per head of cattle available. Provide plenty of water, 2-3 gallons of water per 100 pounds of body weight per animal. Water should not be extremely hot. If pipes or hoses transporting the water to the trough are in the direct sun the water will be hot. Precautions should be taken to cover or bury the pipes or hoses. For cattle in barns, fans and sprinklers can assist in reducing the temperature and increasing the air flow. Rotating or working cattle in the early morning or late evening will reduce the amount of stress they encounter. You should provide free-choice minerals and salt so cattle can replenish the amount lost and meet their needs. Feeding cattle in the early morning or late evening will increase their feed consumption, reducing the amount of weight that is lost. Flies and other external parasites should be controlled. When there are excessive flies and parasites around cattle they tend to bunch up, increasing temperatures.

Another method to help with heat stress in your herd is to incorporate brahman genetics or select cattle that are adapted to Florida’s weather conditions. The skin pigment of brahman cattle is dark and protects against UV damage from solar radiation. Shorter hair coats allow the animals to sweat more efficiently, larger sweat glands allow the animals to sweat at a higher rate, and light-colored hair reflects radiative heat.

Some cattle are at a higher risk for having increased problems with heat stress. These cattle are those that were recently stressed from transporting or processing, sick cattle, dark hided cattle, heavily bred, older and reduced body condition score or thin cattle. We will never be able to make all cattle 100% comfortable. But it is important to take the necessary precautions to reduce as much stress on the cattle as possible. The more the cattle are under stress the more profits are lost.

For more information, please contact your county extension agent.

____________

Sources:

Boyles, S., Heat Stress and Beef Cattle, https://agnr.osu.edu/sites/agnr/files/imce/pdfs/Beef/HeatStressBeefCattle.pdf

Eirich, R and Wpp;spmcrpft, M., Heat Stress: Handling Cattle Through High Heat Humidity Indexes, https://beef.unl.edu/beefwatch/heat-stress-handling-cattle-through-high-heat-humidity-indexes

Davila, K. S., Hamblen, H., Kikmen, S., Hansen, P., Thrift, T., and Mateescu, R. Incorporating Brahman Genetics in the Cow Herd to Alleviate Heat Stress, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AN366

Irsik, M., and Thrift, T., Emergency Considerations for Beef Cattle, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/VM117

0

0