Between 1930 to 1949, Extension played a significant role in turning around Florida’s cattle industry, and changed the landscape of the state forever.

The Cracker Kingdom

There have been cattle in Florida ever since Ponce de Leon brought them to the new world in 1521. When conflicts with the Calusa Indians caused his second expedition to flee, the cows they left behind were small, wiry animals of the Andalusian “criollo” breeds, uniquely adapted to Florida’s climate. Decades later, Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries near St. Augustine became the first ranchers in Florida, with help from local Indian tribes. English settlers and Seminoles took up ranching after the Spanish left Florida in the 1700s, and the herds expanded throughout the state. During the Civil War, Florida became the main supplier of beef to the Confederate army, but it was during the reconstruction period, when a thriving trade opened up with Cuba, that the cattle industry really entered its golden age.

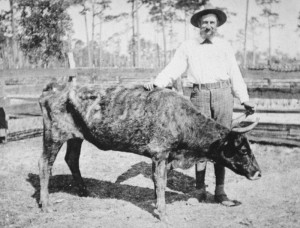

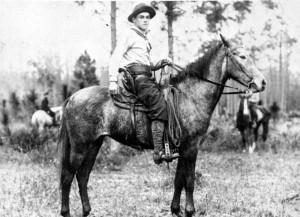

A typical Florida rancher in those days lived on a small homestead of about 80 to 160 acres, and owned 1,000 to 2,000 head of criollo and longhorn cattle. Calves and cows he kept penned in on his property, to protect them from predators and rustlers and provide milk and fertilizer for his own use. But his steers he left to roam free, grazing on wiregrass and saw palmetto across thousands of acres of unfenced, public and privately owned land. Often, a rancher saw his cattle only once or twice a year, when it was time to drive the herd to market. To help in this long and arduous task, he relied on “cow hunters”— ranch hands who rode the open range on small horses, finding errant cows and pulling them from pine woods and palmetto stands. Aiding them were two trusty tools—their cow dogs and their buckskin whips. The cow hunters would crack their whips to run the cattle and signal to other cow hunters. The sound of these cracking whips—which could be heard for miles on a windless day—became so associated with Florida cow hunters they were known as “crackers,” and their steers “cracker cows.”

When the cattle were finally rounded up, they’d be driven to markets in Jacksonville, Pensacola or Tampa, where they’d be boarded on steamships bound for Cuba, in exchange for gold doubloons that made ranchers, on their small homesteads miles away, wealthy enough that their names—Carlton, Lykes, Summerlin, Hendry and many others—are still well-known today.

Tick Fever, Arsenic and Barbed Wire

When the Cooperative Extension Service started up in Florida in 1915, the state’s cattle industry, second only to Texas’, needed little help in thriving, but over the next few years, it was hit by a number of major setbacks. The Cuban market declined in the 1920s, and the domestic market for beef favored robust stock from the American Southwest over Florida’s leaner “scrub cattle.” Attempts were made to improve Florida’s stock by importing other breeds, but they were thwarted by the spread of bovine piroplasmosis, or Texas tick fever. As its name implies, the fever is spread by tick bites; native free-range cattle were generally immune, but they carried the disease-ridden ticks to the imported cattle, killing nearly all of them.

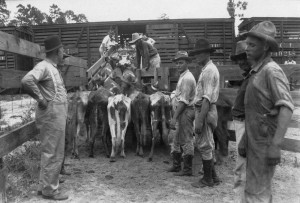

The situation became so critical that in 1923, the Florida legislature enacted a compulsory tick eradication program. With the help of the USDA, vats of arsenic were constructed to dip the cattle every 14 days until each herd was tick-free. In order to quarantine the treated cattle, ranchers had to fence them in. The days of open range and cattle hunting were over, at least for a time. At first, some of the less wealthy cattlemen resisted the eradication program, and several of the arsenic vats were dynamited. Many cattlemen sold off their entire stock ahead of the eradication program; between 1925 and 1930, the number of cattle in the state declined by 35 percent.

Extension Helps to Turn the Industry Around

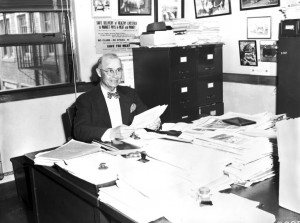

By 1930, the eradication program had succeeded in making north and western Florida tick-free. Cattlemen in these areas were eager to regain their business, but recognized that they needed to make some changes. To respond to cattlemen’s needs, in 1930 the Extension service developed an animal husbandry program and hired its first fulltime husbandman, Walter J. Sheely. Sheely immediately began an ambitious project to help turn the Florida cattle industry around by assuring that cattle were better bred and better fed.

In tick-free areas, Sheely and other agents helped ranchers buy purebred Angus, Hereford and Brahman bulls to breed with cracker cows and produce bulkier calves suited to Florida’s climate. The Florida Cattlemen’s Association, founded in 1934 with the help of Osceola County agent June Gunn, convinced bankers to back “cattle loans” so that ranchers could buy new bulls.

Ranchers needed better, more nutritious pasture to support their upgraded cattle. Using research from the Agricultural Experiment Station, Extension conducted courses and field days to demonstrate methods of improving pasture grasses, the importance of feeding cattle silage over the winter, and how to properly inspect and care for their animals. One important side effect of the tick fever epidemic was that it convinced cattlemen they couldn’t allow their herds to remain uncared for.

Sheely’s ambition paid off–within 3 years, Florida’s cattle population had increased by 11 percent, the number of breeders of purebred cattle more than doubled, and the average annual calf crop rose to 30 percent.

With the cattle population on the rebound, improving the market value of Florida beef became the next objective. In 1935, Extension organized the first Florida Fat Stock Show at Jacksonville to help improve the market for Florida cattle; the show helped attract out-of-state buyers and ran annually until the 1940s. Sheely’s office also conducted meat cutting courses, organized 4-H calf-raising programs, and produced brochures, radio shows and filmstrips to promote Florida beef.

Screw Worm, and a New Research Center

But just as the Florida cattle industry was making a comeback, another scourge struck cattlemen in the form of the parasitic screw worm. Some claimed that screw worm was spread in Florida through “Dust Bowl” cattle that were imported from the Midwest. Controlling the spread of screw worm required that ranchers carefully inspect their animals and laboriously remove the parasites by hand, and once again build fences and pens for quarantine. Screw worm would continue to plague Florida cattle until the late 1950s, when UF entomologists developed sterile screw worm pupae and dropped them by airplane over cattle ranges.

To further its commitment to improving the cattle industry, in 1941 the University of Florida broke ground on the Range Cattle Research Station in Ona, Florida. Later named the Range Cattle Research and Education Center, the Ona facility was established to learn how to produce better quality forage grasses and investigate the breeding, feeding and management of beef cattle in central and south Florida. Today, the Range Cattle REC is a state-of-the-art research center that offers field days, short courses and forage testing programs on more than 2,840 acres of native and developed pastures, with approximately 1,200 head of cattle.

The End of the Open Range

Eventually, the pressures of infectious diseases, the need for improved pasture, and Florida’s growing population forced more and more cattlemen to permanently fence-in their herds. After the state legislature passed the Murphy Act in 1937, allowing the sale of tax-delinquent land, many ranchers were able to buy vast tracts of pasture land cheaply; the average land holdings of ranchers jumped from 88 acres to 870 acres. The final blow to the open range came in 1949, when Florida became the last state in the union to pass a mandatory fence law. Extension, a longtime advocate of fencing, was able to help ranchers acquire timber cheaply and demonstrate how they could treat fence posts against weather damage.

Within twenty years, Extension had helped completely transform Florida’s cattle industry from a break-even existence to a major part of the state’s economy. As a cost of progress, it had also helped change the landscape of the state and end a centuries-old way of life forever. Gone were the days of cracker cattle and cow hunters wandering open prairies of palmetto palm, wiregrass and scrub pine; in its place were large fields of green pasture, hay rolls and high-shouldered Brahmans that graze behind fences along the highway.

Sources:

Akerman, J. A. 1976. Florida Cowman: A History of Florida Cattle Raising. Kissimmee, FL: Florida Cattlemen’s Association.

Dawson, C. F. 1902. Texas Cattle Fever and Salt-Sick. Florida Agricultural Experiment Station, Bulletin 64.

Kirk, W.G. 1966. Early History of The Range Cattle Experiment Station Ona Florida. Florida Cattleman and Livestock Journal, June 1966.

Mealor, W.T. and Prunty, M.C. 1976. Open-Range Ranching in Southern Florida. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 66 (3) 360-376

Otto, J.S. 1986. Open-Range Cattle-Ranching in South Florida: An Oral History. Tampa Bay History 8(2): 23-35.

Platt, L. 1998. Judge Platt: Tales from a Florida Cattleman. Gainesville: UF/IFAS Communication Services.

Rey, J. R. 2013. Florida Cracker Cattle. UF/IFAS Extension publication AN-240. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/an240

Sheely, W. J. 1933. Animal Husbandry. In Cooperative Extension Work in Agriculture and Home Economics. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida.

0

0