Extension touches so many aspects of our lives today because it was born in an era of great uncertainty, not only about food and agriculture, but about the quality of life for millions of rural families.

In the decades following the Civil War, many academics, journalists, economists, and church leaders became concerned that the nation’s agriculture was not keeping pace with the social and technological progress of urban, industrialized areas. For this group, which came to be known as the Country Life movement, the chief source of the problem was the lack of opportunities for people in rural areas. Living on the farm has always meant hard work, but post-war labor shortages, isolation, poor working conditions and lack of control over market prices left farm families with little hope for the future. Each year, thousands of rural residents were leaving their farms to seek better opportunities in the cities. If the trend continued, the US economy (still primarily agricultural at that time) would suffer and a way of life would be lost.

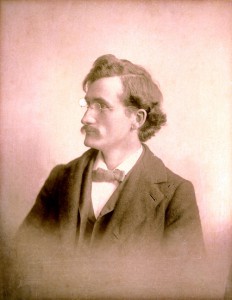

The concerns of the Country Life movement eventually lead to one of President Theodore Roosevelt’s last progressive reform efforts. In 1908, Roosevelt appointed a commission to study the condition of rural life, report on the causes of its deficiencies, and produce a list of recommendations for improvement. To chair the commission, he chose an outspoken and influential professor of horticulture from Cornell University named Liberty Hyde Bailey.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Bailey, one of the leaders of the Country Life movement, believed that the key to revitalizing agriculture was to “awaken” farmers to a new, self-sustaining view of agriculture based on sympathy with nature, a love of country life and a scientific habit of careful observation and experimentation. As idealistic as this philosophy sounds, Bailey was also a pragmatic and effective administrator. In 1894 he was appointed by Cornell to direct the College of Agriculture’s outreach program; by instituting farm demonstration work, biological studies and correspondence education, he soon transformed the program into the first permanent agricultural extension service in the land-grant university system.

Under Bailey’s leadership, the Country Life Commission produced a substantial report at a pace unthinkable in today’s era of beltway gridlock: Between August and December of 1908, the commission solicited a half-million questionnaires from farmers, business leaders, educators, civic and religious leaders; held 30 hearings in regions across the country; compiled the data; drew up individual reports and filed their conclusions—all in four months.

The commission isolated a number of deficiencies hindering people in rural areas, including a lack of knowledge among farmers about the potential of their own land, obstacles to gaining fair profits, lack of farm credit, soil depletion, poor highway facilities, inadequate education in public schools, the burdens and narrow life of women and children on the farm, and the lack of public health information.

Recommendations included a closer study of country life, a campaign for rural progress, and most importantly, a nationalized extension service operating out of land-grant universities, designed to “forward not only the business of agriculture, but sanitation, education, home making, and all interests of country life.”

The Commission’s report was issued to Congress in February 1909, and at first went nowhere. Roosevelt left office a month later, and his successor, William Howard Taft, had little interest in the report. The McLaughlin bill, introduced later that year, had a provision for creating a national extension service, but stalled in Congress because it failed to include the Department of Agriculture, which had already been doing farm demonstration work under the direction of Seaman Knapp.

It would be several years before the recommendations of the Country Life Commission was taken up again, when Senator Hoke Smith of Georgia and Representative Asbury Lever of South Carolina would simultaneously introduce bills that would lead to the Smith-Lever Act of 1914, which permanently established a national system of extension work.

According to the Smith-Lever Act, the purpose of extension work was to “aid in diffusing among the people of the United States useful and practical information on subjects relating to agriculture and home economics, and to encourage the application of the same.” The meaning behind the dry language of the law was clear: Extension should help to improve not only agriculture, but the quality of life for all Americans.

Source: ICS Photo Archives

Florida’s extension system formally began in 1915, and one of its chief objectives was improving the nutrition of farm families. One Extension agent, addressing an audience in 1952, recalled efforts to combat malnutrition in the early part of the century:

When it was said at the time of the birth of this new system of education that the winter diet of the great masses of rural people was “fat bacon, collard greens and corn pone,” it was not just a figment of someone’s imagination but a reality. Pellagra and other nutritional diseases were prevalent in Florida as well as in other states. If the health of the people were to be improved this problem must be attacked and solved…The growing and use in the diet of greater varieties and seasonal plantings of vegetables were demonstrated and promoted. How to preserve spring produced eggs for winter use in water glass was taught. A succession of chick hatching was recommended to give a succession of broilers and fryers for use. Cool springs and deep wells were the only refrigerators available. How to build and use the iceless refrigerator was shown and learned. Fresh meat “rings” were organized and “cooking bees” were held. Canning in glass, then in tin with “cap and tipping steel and finally “crimping” the cap on and processing in “steam pressure cookers” were demonstrated many, many times – over and over again…All of this was done that “our people might live a little better.” What has all this been worth? No one knows, but all will agree its effects have been tremendous and helped considerably along the road toward a better and more satisfying rural life.

It’s this concern, not only for better agriculture, but better lives for people everywhere, that has allowed Extension to adapt with the times and expand with our diverse population. Country Life today is a better quality of life for everyone.

Sources:

Peters, S.J. 2006. “Every Farmer Should Be Awakened”: Liberty Hyde Bailey’s Vision of Agricultural Extension Work. Agricultural History, 80:2.

Report of the Country Life Commission. 1909. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office.

Smith, J. Lee. 1953. Tracks of Men: A Type of Agricultural Extension History. Unpublished manuscript.

Wunderlich, G. 2004. Two Essays on Country Life in 20th Century America. Denver, CO: Address to American Agricultural Economics Association.

0

0