The State of Florida Citrus

Florida has always been known for its citrus production. If it weren’t called the Sunshine State, it could be known as the Citrus State. After all, the state flower is the orange blossom. In the early 2000s, Florida had around 750,000 acres of citrus production. Three times as many acres of citrus as the next largest citrus producer, California. In 2004, a bacterial disease called citrus canker was discovered in Dade County, Florida. It caused panic in the citrus industry. The threat of canker, although grave, was soon replaced by a more significant danger. In 2005 a disease called Citrus Greening was discovered in Florida groves.

A Challenging Disease

In China, citrus greening was known as Huanglongbing. Roughly translated, it means yellow shoots disease. This name probably pertains to the small yellow leaves shooting out from the trees during the last stages of the disease. Researchers shortened the name to an Acronym, now referred to as HLB. Unlike Citrus Canker, which was spread by wind, rain, animals, people, and equipment and manifested on the leaves, stems, and fruit of the plant, HLB requires a tiny insect called the Asian Citrus Psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama, to inoculate each limb with the disease.

A Small Bug with a Big Impact

Asian citrus psyllids feed and lay their eggs on the tender new growth of citrus. An adult citrus psyllid is no longer than 3-4mm and appears as a tiny leaf hopper (Figure 1). From tiny yellow eggs (Figure 2), less than a mm long, psyllids hatch into nymphs. Nymphs are yellow-orange in color with red eyes. The five nymph stages, called in-stars, will molt four times, each time becoming a little larger in size (Figure 3). On the fifth molt, they will become winged adults who are fully capable of reproducing. Nymphs and adult psyllids carry the disease after feeding on infected trees. It can grow within them for most of their lives without affecting their health. They will remain able to infect the limbs they feed on for the rest of their lives.

A Slow Death

The paths of the phloem carry the carbohydrates downward and outward to leaves, stems, and roots. The disease can follow these pathways but does not go upward. When most phloem pathways become burdened with the bacteria, the roots begin to recede and no longer support the tree canopy. Common symptoms are leaves with asymmetrical patterns of green and yellow, termed blotchy mottled (Figure 4). Other symptoms are small and lopsided fruit, thinning of the tree’s canopy, and groups of upright small yellow leaves that appear toward the end of the tree’s life.

A Struggling Industry

From 2005 until now, HLB moved swiftly across all citrus-producing counties of Florida. The results have profoundly affected the industry; many citrus groves stopped making a profit, leading growers to abandon them. From 750,000 acres in production, there are closer to 350,000 remaining. Those remaining groves are less productive, and the total production in Florida is down by nearly 80%. Growers that remain have seen profit margins cut by increases in inputs such as increased spraying and higher fertilizer prices.

Keeping Citrus Productive

Researchers have been working on solutions from many angles and have yet to find a silver bullet. Despite the struggles, some growers are still planting new groves. Young trees are particularly hard to protect from HLB. Because of the nature of how the psyllids move the infection around the tree. With fewer limbs and frequent flushes, new trees quickly become totally infected and may never have the opportunity to produce. Growers have been using insecticidal drenches on trees containing pesticides that travel systemically throughout the trees and kill insects that feed on the trees. While this slows down the infection rate, it is still not enough. Psyllids typically infect young trees to some extent within the first six months after planting. This rapid infection rate, combined with the risk of insects developing resistance due to overuse of pesticides, necessitated the development of alternative protection methods.

Excluding the Insect from the Tree

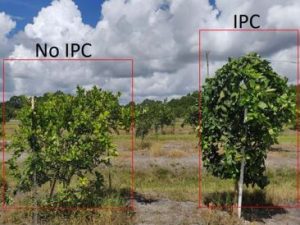

Researchers have developed Individual Plant Covers (IPCs), which growers now use successfully to protect citrus trees. These finely meshed bags, made from sturdy nylon material, cover young trees at planting time. The design prevents adult psyllids from entering and infecting the trees. IPCs range from 4 to 8 feet tall, with some larger versions recently entering the market. University of Florida researchers have studied IPCs and found them highly effective in preventing HLB infection in young trees. Their studies showed that trees could remain in IPCs for 30 months without infection. Additionally, they observed that trees grown in IPCs grew larger than those without protection. (Figure 5)

Some Issues of Concern

IPCs presented some problems despite their benefits. While they protected trees from psyllids, other insects like scales and mealy bugs appeared more frequently. This likely occurred because the net’s mesh was too coarse to exclude them, and once inside, natural predators couldn’t enter to control their populations. IPCs also increased the incidence of greasy spot, a fungal disease. Researchers suspected that the bags created a micro-environment conducive to fungal growth. These two issues would require regular scouting and monitoring. To address insect problems, growers might apply limited insecticidal systemic drenches, though less frequently than on uncovered trees. For fungal pathogens, they would need to monitor and spray as needed. Heavy winds posed another challenge for IPCs, especially in Florida, which often experiences tropical weather. Unsecured IPCs risked blowing off during strong gusts. (Figure 6)

A Larger Type of Cover

Another method for excluding citrus psyllids is Citrus Under Protective Screens (CUPS)(Figure 7). These are large metal framed structures covered with nylon mesh, much like the IPCs are constructed of, and are large enough to cover an entire grove and tall enough to protect full-grown trees. Early trials with them have been successful, although the structures can cost as much as one dollar a square foot. Because of this, they will likely be reserved for growing fresh fruit crops instead of citrus for juice.

Where we go Now

Using IPCs has limitations, but early results have been promising. The question of what to do when the IPCs are removed is a continuing challenge. Continued use of system pesticides and regular spraying to limit psyllid populations will likely remain the approach. Breeding improved rootstocks and tolerant varieties are being worked on, but those types of solutions take time and testing. Injections of antibiotics are a treatment that has shown some success, but the cost and labor will likely become a factor. For now, using IPCs seems to be a sustainable low-pesticide approach that will give young trees a better chance to remain productive longer.

“Follow” and don’t miss out!

That’s what’s new from the Hometown Gardener, “follow” me on Facebook at Hometown Gardener to keep up with

horticultural happenings in the Heartland.

Stay in touch!

Sign up for our Highlands County Master Gardener Volunteer, “Putting Down Root” Newsletter Here

That’s what’s new from the Hometown Gardener. Like and Follow me on Facebook at Hometown Gardener.

Read my other blogs by clicking here.

Join our Facebook groups Highlands County Master Gardeners, Science-Based Florida Gardening Answers, Central Florida Butterfly and Pollinator Club, and Heartland Beekeepers

0

0