The Florida Chapter of the International Society of Arboriculture has established itself as a significant funder of tree care–related research and education. Its grant program has supported, among other things, the publication of a Florida-specific wood decay field guide. It is currently underwriting the completion of my latest work, a field guide to Florida urban palm identification.

As we begin 2026, this post serves as a final accounting of a Florida Chapter–funded research project that I have had the good fortune to work on for the past three years. The project originated from a research question posed by the grant committee itself as a priority area: Can an understanding of woody root biology help us design sidewalks that don’t crack or lift in the presence of trees?

A Plan of Attack

To address this question, I conducted a deep dive into the root growth literature, only to find that research on the pressures generated by radial root growth is somewhat limited. Nearly all existing studies have focused on agricultural crop seedlings and radicle expansion (i.e., the first root to emerge). The sole exception was earlier work by my project partner, Jason Grabosky.

As documented in this post, this gap created an exciting opportunity to explore a new research direction. Specifically, we designed root clamps using elastic bands that ratcheted up in tension as the roots they contacted expanded and pulled the bands taut. We submitted this design as part of our research proposal. The methods must have passed muster, as the grant was funded—and we were then charged with actually doing what we had proposed.

This led to the most nerve-wracking research experience I’ve had to date. We had to determine an appropriate range of tensions to elicit the flattening growth response we were hoping for within the timeframe of the study. Complicating matters, half of the trees were located in a landscaped area maintained by contracted lawn crews, which meant the root clamps needed to be accessible for monitoring yet protected from the occasional zero-turn mower tire.

Ultimately, it all worked out. We housed the clamps in irrigation valve boxes, which provided both access and protection. The roots grew quickly enough to stretch the bands and restrict radial growth within the necessary timeframe, and the materials proved durable, surviving without degrading or breaking down.

The Limits of Radial Root Expansion

By the end of the experiment, we had assembled a solid sample of roots that had flattened and those that had not, along with the associated tensions each experienced. This provided a strong dataset for my go-to analytical approach: logistic regression, which predicts the likelihood that an event occurs (flattening, in this case) versus not.

Despite my affection for this statistical model—and my years in academia—I recognize that its output isn’t especially intuitive. Estimating the natural log of the odds of an event occurring doesn’t resonate with practitioners focused on preventing tree-related damage to infrastructure. With a bit of mathematical wizardry—and a careful review from my daughter’s calculus tutor—we translated the results into something more practical: an estimate of the pressure a sidewalk must withstand to resist cracking or lifting.

When confined by pressures of approximately 0.329 MPa (about 48 psi) or greater, roots were no longer able to expand radially and instead flattened beneath sidewalks. This estimate aligned well with earlier work by Jason and fell within the range reported in previous seedling studies. The paper is currently in press.

How Roots Influence Sidewalks

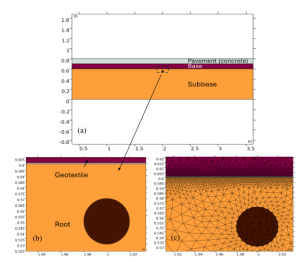

The second key outcome was an engineering assessment of how a growing root affects a typical sidewalk. Leading this effort was Sharef Farrag, an engineer from Rutgers University who now works for a firm assessing bridge safety. Sharef conducted a series of computer simulations called finite element modeling, which allowed him to test how a concrete sidewalk would behave under various conditions—in our case, roots of different diameters and depths applying upward pressure.

Interestingly, the pressures we observed (and others have reported) were not sufficient to crack a sidewalk on their own. There has been ongoing debate about whether roots actually cause sidewalks to crack, or if they are simply drawn to cracks created by soil movement (shrinking and swelling), where moisture is trapped beneath the pavement and oxygen exchange occurs through the break in the concrete. Based on his simulations, I am leaning toward the latter explanation.

That said, there is more than one way to crack a slab. While the upward pressure associated with radial root expansion may not be enough by itself, downward pressure from foot traffic or other loads could initiate cracks. Once a crack forms, the root pressures we observed were sufficient to lift the sidewalk in our simulations.

Designing Better Sidewalks

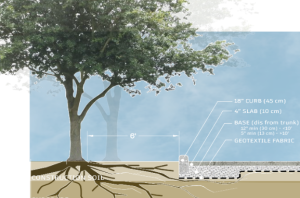

We then asked Sharef to design a more resilient sidewalk, keeping in mind that the simplest and most cost-effective solution is usually best. I had my own ideas—embedding reinforcing wire in the slab and using earth augers to hold the sidewalk down—but Sharef’s solution was far simpler: just increase the depth of the gravel base beneath the sidewalk.

Unbeknownst to Sharef, Ed Gilman had conducted a study on deflecting roots under sidewalks, published in 2006. This study evaluated a range of commercial barriers and treatments, and a gravel layer proved the most effective at keeping roots beneath the bottom of the slab. I love it when things line up like this. Not only does the gravel layer, according to Ed’s work, deflect roots downward, but Sharef’s model shows it also provides sufficient support to prevent cracking for the roots that do grow there. Two independent studies pointing to the same conclusion—that’s more than we often get in arboriculture!

About this blog

Rooted in Tree Research is a joint effort by Andrew Koeser and Alyssa Vinson. Andrew is a Research and Extension Professor at the University of Florida Gulf Coast Research and Education Center near Tampa, Florida. Alyssa Vinson is the Urban Forestry Extension Specialist for Hillsborough County, Florida.

The mission of this blog is to highlight new, exciting, and overlooked research findings (tagged Tree Research Journal Club) while also examining many arboricultural and horticultural “truths” that have never been empirically studied—until now (tagged Show Us the Data!).

Subscribe!

Want to be notified whenever we add a new post (about once every 1–2 weeks)? Subscribe here.

Want to see more? Visit our archive.

9

9