Franklin County is fortunate to have an abundance of salt marshes fringing our coastal environs. Although this habitat may not receive the appreciation it deserves by those seeking a white-sandy beach, it is intricately linked with many of the natural treasures we possess in this Panhandle wilderness County. Salt marshes occur in the ecotone where the land connects with the salty water and they are occupied by a special assemblage of salt-tolerant, hydrophytic plants that provide benefits on many levels. Literally, levels that stretch vertically from the substrate to the tops of the grasses, and horizontally as the plant species are arranged into different zones, depending on water depth.

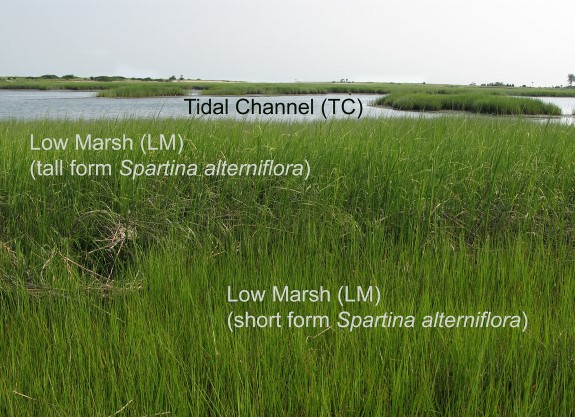

The classic salt marsh vegetation zones, looking from the land outward, begin with the high-marsh which only gets inundated by extremely high tides. This area is usually dominated by a grass called marsh hay (or salt meadow) cordgrass (Spartina patens) that grows in wiry-leaved clumps. You can also find salt grass (Distichlis spicata) which has shorter, flat leaf blades that project from the stem at a distinctive angle. The mid-marsh zone is typically in and out of the water on daily tides and is dominated by a type of rush called black needlerush (Juncus roemerianus). The low-marsh grows in an area that stays under water much of the time and is inhabited primarily by smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora).

Ecologically speaking, you might gather that salt marshes are not incredibly diverse as far as plant species. However, the structure, cover and vegetative food components that are available here support a tremendous assortment of animals, some that we depend on for seafood and others that are simply a pleasure to know about. Many species utilize these grassy, nearshore areas during the juvenile portion of their life cycle. Baby crabs, shrimp and fish find many of their needs met here. Just spend a few minutes quietly observing in this habitat and you’ll be amazed when you notice the baby mullet, killifish, fiddler crabs, and a host of other creatures going about their “marshy” business. It is also a special treat to conduct a nighttime search with a flashlight here. Just wear protective shoes, as oysters often grow in these places also.

One group of animals that depends on this habitat is our coastal birdlife. In fact, there is a subset of birds that has been dubbed with the title of “secretive marsh birds,” because they rarely come into the open where people can see them. This group includes several species of rails, bitterns, gallinules and others. Scientists have been concerned about declines in many of these species so standardized methods have been developed to survey them using broadcast recordings to elicit vocalizations that can be counted. Salt marshes are also important nesting habitat for species such as seaside sparrows, marsh wrens, red-winged blackbirds and many more. Winter visitors like Northern harriers soar low over our marshes hoping to catch a sparrow napping.

Last but not least (in my book, of course) are a couple of reptiles that can be found in our saltmarshes. The gulf salt marsh snake (Nerodia clarkii) uses the marsh for cover and to find its preferred diet of small fish, crabs, shrimp and other invertebrates. They spend their days generally hiding under debris, being more active at night. They can be recognized by their four lengthwise yellowish stripes and the fact that you aren’t likely to find another snake in the saltmarsh. However, I have seen a cottonmouth or two spending time here, so be careful. The other unique reptile we can find in coastal marshes is the ornate diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin macrospilota). These charismatic coastal turtles are sexually dimorphic, with males only reaching about five inches and females growing to around eight inches. The yellow centers on the dark scutes of the back are a definitive identification feature, along with very pale gray skin that may be speckled with black dots.

Terrapins feed primarily on mollusks and crabs and use the adjacent upland areas for laying their eggs. Terrapins have suffered dramatic declines throughout their range because they are attracted to the bait in crab traps and can be trapped and drowned. There is a simple solution though. If you ever find terrapins in your traps you can install a rectangular exclusion device that will keep out terrapins but let crabs through. Email me if you need some at elovestrand@ufl.edu.

Take some time to visit our incredible coastal marshes and appreciate the diversity of life, along with the most profound serenity provided by the scenic vistas that open before you.

0

0