For almost 40 years, the Ocean Conservancy has held the International Coastal Cleanup in September. Across the planet hundreds of thousands of volunteers clean marine debris from their shorelines. The data collected is used by local agencies to manage this problem; such as discontinuing the use of pull tops from aluminum cans. In the last couple of years researchers are trying to make the public aware of another form of plastic most know little about – microplastics.

“Nurdle” are primary microplastics that are produced to stuff toys and can be melt down to produce other products.

Photo: Maia McGuire

Microplastics are defined as pieces measuring 5 mm in length or smaller. These can be large pieces of common plastics that been degraded by sea and sun. They can be small pellets called nurdles that are melted down and poured into molds to produce common plastic products or used to stuff toys. They can also be small beads used as fillers in personal care products, such as toothpaste. Those that are manufactured at this size are called primary microplastics; those that degrade to this size are secondary microplastics.

How Do They Find Their Way to Local Waterways?

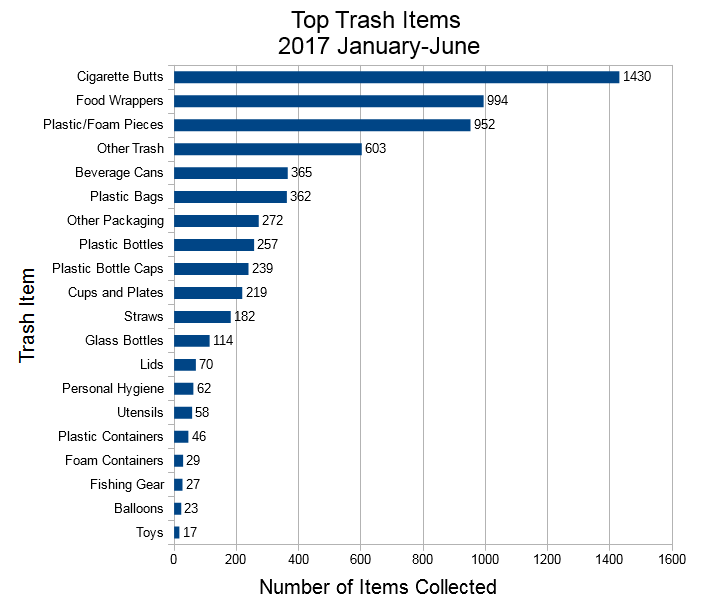

The sources of secondary microplastics is obvious. We either intentional or unintentionally discard our waste into the environment. According to data collected by the local nonprofit group Ocean Hour, cigarette butts are the number item collected during weekly cleanups. Many are not aware that much of the material in a cigarette butt is actually plastic fibers, and many butts are tossed to the ground intentionally. Adhered to these fibers are the products of smoke we are concerned with in our own health – tar, nicotine, and ethylphenol.

Ocean Hours data show other forms of plastics (bags, wrappers, cups, bottles, and caps) are very common. These items are discarded directly, or indirectly, into the environment and eventually end up in our bays and oceans – “all drains lead to sea kid”. Here they are eventually broken down. Some scientists believe all the plastic ever produced is still in the sea, continuing to breakdown smaller but never really going away. I viewed a webinar within the last year where a researcher from the west coast was discussing the “great plastic island” in the Pacific. She showed a photo from the location and you did not really see a lot of large plastic drifting. However, a plankton tow revealed large amounts of microplastics.

Less common are the primary microplastics… but they are there. According to our monitoring in the Pensacola Bay Area, they make up about 20% of the microplastics found. When we wash our faces, or brush our teeth, with plastic filled products these microplastics are washed down the drain to the local sewer treatment facility. Here they remain on the surface of the water that is being treated and are eventually discharged into wetlands, or directly into a water body.

Are These Microplastics Having a Negative Impact on the Environment?

Locally, we are monitoring 22 stations. We are finding an average of 9 pieces of microplastic / 100ml of sample (little more than 3 ounces). This equates to a lot of microplastic in our bay. Science does know that these are small enough to be swallowed by zooplankton in our water column. It plugs their digestive tract and gives them the sensation of being full. Thus, they stop eating and starve. A decline zooplankton, a key component of most aquatic food chains, could affect economically important members higher up the food chain.

Laboratory studies show it may be affecting lower on the food web. When subjected to water containing microplastics, the microalgae Chorella reduced its uptake of carbon dioxide; thus reducing photosynthesis.

In larger species, microplastics have been found in the tissue of some bivalves, including those commercially harvested for human consumption. There is little evidence connecting health related problems of either the bivalve or the human consumer, to microplastic consumption – but there is concern.

There is evidence showing chemical contaminants adhere to the plastics and can increase their concentrations 1 million times. Swallowing plastics with high concentrations of Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and DDT (all of which have been found on microplastics) could be problematic.

There is also concern of bioaccumulation of these contaminants as they move through the food chain, but little evidence that it does. There is also little research on the leaching of toxic products from these plastics and their impacts. In his recent publication on the status of water quality in Pensacola Bay, Dr. Mike Lewis agrees that more attention needs to be paid to microplastics.

These microfibers are from the inside of cigarette butts and a common form of microplastic in our waters.

Photo: Maia Mcguire

What Can We Do About the Microplastic Issue?

- Cut back on your use of plastics. Easier said than done, our world is full of plastic, but there are a few things you can do:

- a) choose not to use straws when eating out.

- b) purchase a good water bottle and take it with you. Many locations where we purchase coffee or fountain drinks you can use this bottle instead of their foam or plastic cups.

- Change your habits and product choices.

Personal care products with microplastics will have polyethylene on the ingredient label; if it does – choose a different one. There is a website that lists many of these products.

Http://householdproducts.nlm.nih.gov.

- If possible, wear clothing made of natural fibers.

Being aware of the microplastic problem is the first step in correcting it.

References

Unpublished data analyzed by the Escambia County Division of Marine Resourc

es and Florida Sea Grant.

Yang, Y., I.A. Rodriguez-Jorquera, M. McGuire, G.S. Toor. 2015. Contaminants in the Urban Environment: Microplastics. Electronic Data Information Source (EDIS). 6 pages. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/SS/SS64900.pdf.

0

0