People enjoy animals. Zoos and wildlife parks are popular tourist destinations and animal programs are popular on television. It is usually the larger predator animals that get our attention. Sharks, panthers, and bears are popular. People like turtles, raptors, and snakes. Other animals are popular as well like antelope, elephants, and deer.

Photo: Mike Sandler

At public aquariums you see exhibits with whales, sharks, and sea turtles. You also see tanks with reef fish, crabs, and octopus drawing crowds. But one group of animals that has never really drawn attention – either at public parks or wildlife television shows – are worms.

Worms are a world of the creepy and gross. To us, their presence suggests dirtiness or environmental problems. But worms are abundant in our environment and play an important role in ecology. In this series we will meet some of them and learn more about their lives. We begin with the flatworms.

As the name suggests, flatworms have flat bodies. In many species their heads can be identified by the presence of eyespots. Eyespots differ from eyes in that they detect light, but do not provide an actual image. Biologists describe animals as being either positively or negatively phototaxic. Most flatworms are negatively phototaxic, they do not like light. To them, light indicates daytime. A time when the predators can see and attack them. So, when they detect light, they move under rocks, mud, whatever to avoid being detected.

Most flatworms are less than 10mm (0.4 in) in length, though some are 60 cm (24 inches). They possess a mouth on their belly side (ventral) and often it is in the middle of the animal, not at the head end. This mouth leads to a simple stomach, but they lack an anus so solid waste must exit the worm through the mouth – what is called an incomplete digestive system.

Photo: University of Alberta

One class of flatworms are the free-swimming turbellarians. Most are carnivorous, feeding on small invertebrates and dead carcasses. Some feed on sessile creatures like oysters and barnacles. And some feed on microscopic plants like diatoms. The carnivorous species wrap their prey with their bodies secreting slime over them. They engulf their prey whole. There are two classes of flatworms that are parasitic: the trematodes (flukes), and the cestodes (tapeworms).

Flatworms lack an internal body cavity (coelom) and thus lack internal organs. Not having lungs and kidneys they must take in need gases, and other materials, and well as expel nitrogenous waste, through their skin. Being flat increases their surface area and the efficiency of doing this. This is why they are flat.

Reproduction in flatworms occurs in different ways. Some will reproduce asexually by simple fission – they split apart producing two worms. Many species reproduce sexually using sperm and egg.

Another class of flatworms are the parasitic trematodes; commonly called flukes. They resemble turbellarians in body shape and design, though the mouth is usually at the head end. Most are only a few centimeters long, but one can reach the length of 7 meters (24 feet)! Their bodies are covered with a skin-like material that protects them from the digestive enzymes of their hosts.

Photo: Kansas State University.

As with turbellarians, flukes are hermaphroditic but use internal fertilization with other worms to produce young, though self-fertilization can – and does – happen. Their life cycles can include one or several hosts. The primary host, the one the adults reside in, are usually vertebrates, most often fish. The intermediate hosts, the ones the juveniles reside in, are often snails but can be other species.

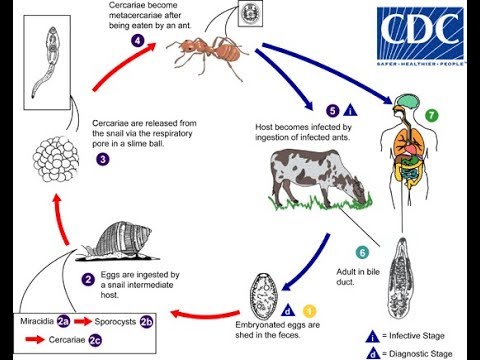

Image: Center for Disease Control

The life cycle is complex, but a general one would include the fertilized eggs being encased in a shell and released into the environment via the feces of the primary host. A ciliated larval stage hatches from this egg and is either consumed by the intermediate host or penetrates the skin of it. Once inside the second larval stage begins. This eventually becomes a third and fourth larval stage. At the fourth larval stage the young worm possesses a mouth and digestive tract. At this stage it leaves the intermediate host as a free-swimming larva seeking a second intermediate host. Here it goes through more larval stages and eventually becomes encased within a cyst (a hard shell). The encysted larva stage enters the primary host (a vertebrate) after that primary host consumes the second intermediate host. Here it develops into the adult trematode.

A third class of flatworms are the parasitic tapeworms – Class Cestoda. Tapeworms differ from other flatworms in that they have a round head – called a scolex – attached to a flat body, and they lack a digestive tract. The flat part of the body is made up of small square segments called proglottids. They continually add proglottids and can become quite long – some have measured over 40 feet! The scolex has four suckers and a ring of small hooks with which they can attach to the inner lining of the digestive tract with.

Photo: University of Omaha.

The reproductive organs occur within the proglottids. Cross fertilization between these hermaphroditic worms is the rule but self-fertilization does happen. The fertilized eggs are released when the proglottid ruptures and exit the host via the feces.

Tapeworms do require intermediate hosts. The extruded egg hatches into a ciliated larva which is consumed by the intermediate host before that host is consumed by the primary host – typically a vertebrate.

As we can see the lives of these flatworms are (1) secretive, and (2) not pleasant to think about. But they do play a role in our marine and estuarine ecosystem and are very successful at what they do. They should be appreciated for their success.

In our next article on the World of Worms we will look at the nemerteans.

Reference

Barnes, R.D. (1980). Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.

0

0