There have been a lot of things brought into and out of the deep South that seemed like a good idea at the time. From kudzu and mullet haircuts to deep-fried Twinkies and jorts, we should probably think twice about a few trends. One such grand idea was the tung oil tree.

Recently, some good friends who have a little piece of property over in Walton County asked me about a beautiful, leafy tree with big green citrus-like fruit growing on their land. They were hoping it was edible. While I wasn’t immediately familiar with it, my horticulture agent colleagues were, and emphasized that it is most definitely NOT something to eat.

Tung oil trees (Vernicia fordii, formerly Aleurites fordii) were introduced along the Gulf Coast from Texas to northwest Florida in the early part of the 20th century as a potential cash crop. In its native range in southeast Asia—particularly southern China—oil extracted from wild tung tree nuts was used to waterproof wooden boats the way we used longleaf pine sap. For centuries, they burned the oil in lamps and used the wood for instruments. Awareness of tung oil reached western civilization via Marco Polo, and later through trading along the Silk Road.

When an American diplomat to China sent seeds of the tung oil tree to contacts in California in the early 1900’s, they did not survive the arid climate. From there, more saplings were sent to agricultural experiment stations across the country to see if they’d perform better elsewhere. Several of the first successful stands of tung oil trees were actually nearby, in Tallahassee and Fairhope, Alabama. Turns out, tung oil trees loved the Gulf South. Our humidity, heavy rainfall, and milder winters felt more like “home” than anywhere else in the country. Enthusiasm about a potential new crop saw the planting of thousands of trees in stretch of the northern Gulf Coast and was deemed the “Tung Belt.”

Most of the plantations were financed and owned by wealthy Midwestern businessmen taking advantage of a program intended to help poor Southerners buy timberland. Tung oil orchards were first planted in the very areas where our longleaf pine forests had been widely clearcut. After establishing tree orchards and hiring local help to harvest, they were hoping to attract industrial processors for paint, ink, and oil using the raw materials provided by the trees. The trees are fast-growing, helping manage erosion, and producing a crop in 3-5 years as opposed to the decades required to harvest pine. Experimentation with the oil increased during World War I. According to the September 1929 issue of the The Journal of American Oil Chemists’ Society, by the mid-1920’s, tung oil was the 4th largest chemical import, and there was a lot of interest in elevating domestic production. The first American oil producing plant was opened in Alachua County, Florida, in 1928, hoping to compete with that huge import industry.

The short-lived effort was first met with great hope for economically and botanically diversifying southern agriculture. Despite great efforts to popularize the tree through “Tung Oil Queen” contests and magazine articles highlighting their lovely flowers, the effort never truly took root. The nascent tung oil industry in the USA lasted through World War II, fueled by rich boosters, government investment, and anti-Chinese messaging. During the war, the federal government commandeered its use for waterproofing clothing, tents, ships, planes, and lubricating machinery. Unfortunately, growers were unable to ramp up domestic production substantially during the short time frame of the war. By the late 40’s, competition from imported products, synthetic oils, and the tree’s vulnerability to freezes led to waning enthusiasm and the industry weakened. It was officially deemed over in 1969 when Hurricane Camille wiped out the last of the orchards.

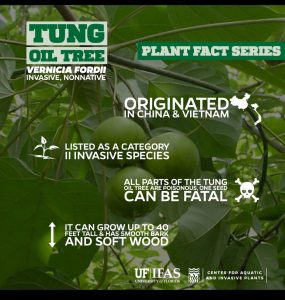

Remnants of these trees still pop up along the northern Gulf coast. Tung oil trees are considered a “species of caution” in north Florida by the IFAS Assessment and a Category II invasive species by the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council. According to the UF IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants, “all parts of the tung oil tree are poisonous, and one seed can be fatal.” Many people have an allergic reaction when touching the leaves, but if leaves or seeds are ingested they can cause extremely serious gastric and respiratory distress.

Remnants of these trees still pop up along the northern Gulf coast. Tung oil trees are considered a “species of caution” in north Florida by the IFAS Assessment and a Category II invasive species by the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council. According to the UF IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants, “all parts of the tung oil tree are poisonous, and one seed can be fatal.” Many people have an allergic reaction when touching the leaves, but if leaves or seeds are ingested they can cause extremely serious gastric and respiratory distress.

Tung oil trees are in the Euphorbia family and are related to rubber trees. The fruit ripens and turns red in the fall. Inside the fruit are nuts with 3-5 seeds, which yield the high-quality oil once pressed. They do have incredibly beautiful, tropical-looking flowers and are still used as ornamental trees in some states. According to Extension colleagues at LSU, a new variety that produces few fruits and no viable seeds has been developed that could be a safer option.

I learned a tremendous amount about this species and how it came to our area thanks to an exhaustive examination of the tung oil industry from a PhD history student out of Mississippi State University. Dr. Snow’s dissertation is a fascinating overview of cultural, economic, agricultural, and world history encapsulated in an oily little nut.

16

16