Ugh, cogongrass. It is a beast of a plant—insidious, stubborn, and overwhelming. Once introduced to an area, it slowly takes over, crowding out native species and reducing previously diverse habitat to an unwelcome monoculture. Like most invasive species, its introduction was innocent enough. Used as packing material for shipping in the days before styrofoam and bubble wrap, it was a cheap and plentiful—even sustainable—material for international commerce. But as living things are prone to do, the grass’s survival instinct won out, with seeds and cuttings escaping from packaging and taking root in their new home of Mobile, Alabama well over 100 years ago. Being a port town, Mobile has the dubious honor of being the point of introduction to several difficult species, including fire ants and cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica). A few years later, cogongrass was planted intentionally as a forage crop for livestock. Unbeknownst to those optimistic cattlemen, the jagged, rough edges of cogongrass are difficult on the digestive systems of animals and they will avoid eating all but young shoots.

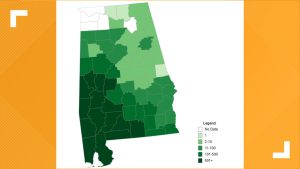

Cogongrass is often spread locally by municipal mowing operations—when a lawnmower or weed eater is used at a park or right of way with cogongrass, then taken to a new location without being cleaned off, pieces of the plant are transported to the next spot and take root. I’ve seen new patches sprout up in city parks, county athletic facilities, and even National Parks. The plant is widespread in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, north Florida, and parts of Georgia, South Carolina, and Texas. Data from 2016 showed cogongrass growing on over 66,000 acres, but that number is likely quite low.

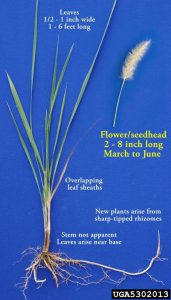

Cogongrass can be identified by its whitish/green tall blades and off-center midrib. If dug up, you’ll find underground runners/rhizomes that have a large spiky protrusion. In the spring and summer, the grass is noticeable due to its large, puffy white seedhead/flowers.

Besides taking over previously native habitat, cogongrass is problematic because of forest fires. Our longleaf pine habitats burn naturally (and sometimes by prescription) every few years, and this is a beneficial part of the ecosystem’s life cycle. However, if cogongrass is growing within an area that catches fire, the grass actually burns hotter than the surrounding vegetation. While a typical fire will burn off the low-growing shrubs and grasses in a forest and spur new growth, a cogon-fueled fire’s more intense heat can often kill the longleaf pines completely. This video from the Alabama Forestry Commission shows just how drastic these fires can be. Because the vast majority of cogongrass’s biomass is underground in its rhizomes, the plant can sprout back up after a fire while other plants struggle to regrow.

Eradication of the plant is difficult, but there are means to control it. If a new patch shows up somewhere, going after it vigorously and quickly can sometimes prevent further spread. A combination of glyphosate (known commonly as Round-Up) and triclopyr is an effective means against weedy vegetation. It should be applied directly to the plant and on a day without wind so none blows to nearby native or desirable species. Typically, multiple applications are necessary and should be conducted in late summer/early fall. On more open farm and pasture fields, our agriculture specialists recommend tilling the fields to break up rhizomes and deplete them of energy. This should also be done more than once, during the growing season and at least 6 inches deep. The disker or other machinery used to till should be cleaned afterwards to prevent further spread of cogongrass.

1

1