After last week’s write-up on cicada killers, it seemed only fair to talk about cicadas this time.

These cryptic insects are seldom seen, but leave plenty of signs they’re around. In many regions of the country, they bunker underground for 13-17 years before a mass emergence. Around here they are present annually, and particularly in the summer you can hear them at night and find their translucent brown molts attached to trees.

As a kid, I was fascinated by them—my friends and I would collect and attach those “locust shells” to our t-shirts in the summer like pins, or gather them en masse to freak out our moms. We used the term “locust” incorrectly—at least where I grew up, it was interchangeable with cicada. There’s a backstory as to why that’s a common misnomer—the periodic mass emergences that occurred “reminded early American settlers of the Biblical plagues of locusts.” Thus, the insects were christened as such, and the name stuck. In reality, cicadas and locusts are two very different types of insects. Locusts are a variety of grasshopper (Order Orthoptera, with crickets and katydids), while cicadas are considered “true bugs” and in the Hemiptera Order with aphids and assassin bugs. In fact, as of 1902, locusts are extinct in the United States—North America is the only continent besides Antarctica without a population.

Despite all the time I spent outdoors in my younger days and now, I have few recollections of seeing an actual cicada. But I did, and still do, hear the whirring, buzzing, rhythmic songs they produce. Florida has 19 species of cicadas, and 14 of them can be heard at this link!

There are about 3,000 species of cicadas worldwide, and the timeframe of their long, rather complicated life cycle varies widely by region. Periodical cicadas are the ones that make the news, emerging as “Brood XYZ” and making the news. Less exciting (but more common) are the annual cicadas, which do spend a few years below ground before emerging as adults on a staggered schedule.

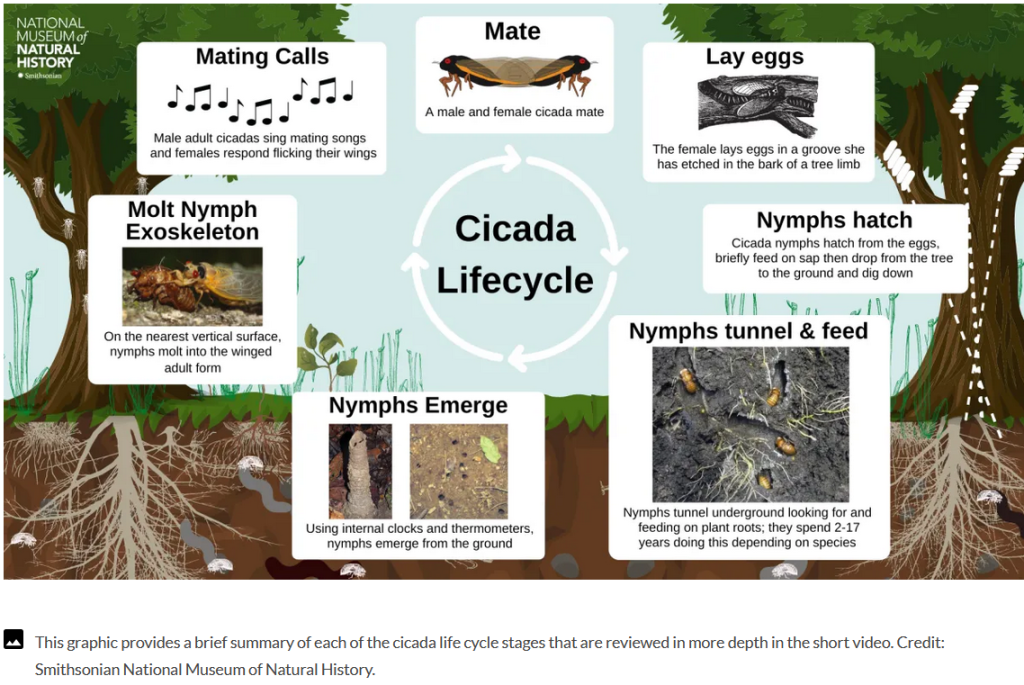

The Smithsonian Museum of Natural History produced a video (screenshot below) that does a great job explaining the life cycle, starting with a mating pair. Females lay eggs in trees, and nymphs begin feeding on the xylem, which carries water and minerals through the tree. Eventually they fall to the ground, and feed on the xylem of increasingly larger roots, starting with grasses and moving to tree roots. They grow and molt multiple times underground. After the appropriate timeline depending on species, the nymphs leave the ground and crawl vertically, usually up a tree (although I’ve seen them on curbs), where they molt and leave their exoskeletons. Free-flying, the males start singing using drum like structures on their hollow abdomens called “tymbals” (rhymes with cymbals). Eventually, they join a chorus of pining males attempting to attract the silent females. Then, the cycle starts over.

Males will also make noise if they’re being attacked by a larger animal in an attempt to startle the predator and escape. Cicadas don’t bite or sting, so this is their only defense. This nonviolent civil disobedience is referred to as a “disturbance squawk,” or the more eloquent “protest song,” which would probably make Woody Guthrie proud.

8

8