Florida’s geology is as varied as its plant and animal life. Here in the western Panhandle, we have extremely sandy soil along the coast and heartier loam, clay, and iron rock as you approach the northern border with Alabama. If you start tracking east and south, you’ll hit more porous limestone rock, a “karst” geology composed of the compressed exoskeletons and shells of ancient marine organisms like dinoflagellates, coral, and sea snails. Springs burst through the surface here, with pore spaces between the calcium carbonate allowing water to well up. Slightly acidic rainfall erodes the limestone, opening bigger spaces for water to move, underwater caverns to form, and sinkholes to open.

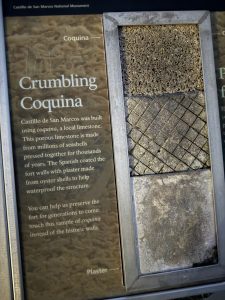

Coquina (Spanish for “tiny shell”) stone is a type of sedimentary rock that forms through pressure, time, and the accretion of sand and shell. It typically builds up in areas of high wave energy, and through erosion, settling, and sorting they develop close-packed layers oriented in the same direction. Unlike many other types of rock, the components are clearly visible. Entire coquina shells are intact and visible in the ancient rock, and look no different than the ones you might find walking along the beach today.

This natural concrete was so abundant along the beaches that huge chunks were cut—like granite from mountains—to build almost everything in early colonial northeast Florida. On a recent trip to St. Augustine, I revisited the impressive Castillo de San Marcos, a 17th century structure that stands as the oldest fort made of brick or stone in the United States. The fort is made completely of coquina rock, which is naturally resistant to the salt spray and tough outdoor conditions that any coastal building must endure. The relatively soft exterior of shell was effective in fortresses, because it absorbed cannon fire instead of cracking the walls.

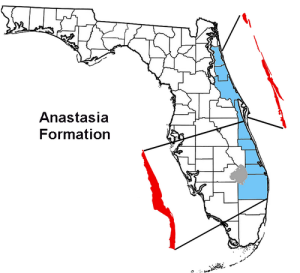

The Spanish utilized a deposit of coquina on nearby Anastasia Island to quarry stone for the fort. The island lent its name to the larger “Anastasia Foundation,” which is the largest concentration of coquina rock in the state. It runs along barrier islands on the Atlantic for over 150 miles from St. John’s County all the way down to Palm Beach County.

Walking through the city, I noticed many privacy walls, homes, and even tombs were constructed of the same material. The first St. Augustine lighthouse and parts of Flagler College were built of this material, as well! It’s fascinating to consider that these 300+ year old structures, particularly massive ones like the fort, are assembled from tiny clam shells.

7

7