According to Conservation International, there are 36 biodiversity hotspots worldwide. These are defined as areas with “at least 1,500 vascular plants as endemics — which is to say, it must have a high percentage of plant life found nowhere else on the planet. A hotspot, in other words, is irreplaceable. It must have 30% or less of its original natural vegetation. In other words, it must be threatened.”

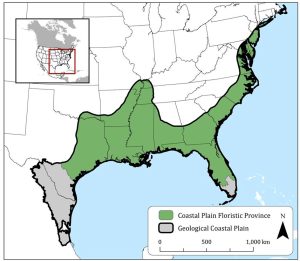

Only two of these 36 biodiversity hotspots lie within the United States, including the North American Coastal Plain, which stretches from Texas along the Gulf Coast and up the Atlantic coast. The state of Florida rests fully within the coastal plain. Within that region, northwest Florida is the hottest “biodiversity hotspot,” one of just six designated regions in North America.

Why us? How did our little corner of the state earn such notoriety? If you’ve ever spent August here, you know how very hot and humid it gets in the summer. As we experienced with the snow and freeze a couple of weeks ago, the Panhandle endures some rather extreme temperatures that fall within our natural range. Our coastal communities sit just above sea level, but we’ve also got hills—while not terribly high (345 feet), the state’s highest point is in Walton County. Along the bluffs of the Apalachicola are whispers of the last Ice Age, where fingers of the Appalachian Mountain range are visible in the same hardwood species and geologic formations typical of north Georgia and Tennessee.

As they say, variety is the spice of life, and this wide spectrum of livable habitats, from coastal marsh to high and dry ridges means we have more options for plants and wildlife to inhabit. The Florida panhandle is home to more than 2500 plant species, 300 species of birds, and 25 species of salamanders, including many endemic species found nowhere else in the world. The oxygen-deprived soils of our flatwood bogs give rise to dozens of carnivorous plant species. They’ve adapted to poor nutrition in the soil by supplementing with insects. Vast waterways mean we have 500 species of saltwater fish and at least 85-90 freshwater fish, including those that live a portion of their life cycle in both.

A project known as the Northwest Florida Greenway Corridor is actively being funded and set aside to create a 150,000 acre conservation region connecting two million acres of protected land including Blackwater River State Forest, Eglin Air Force Base, and Apalachicola National Forest . Along with coastal barrier islands and inland areas of Gulf Islands National Seashore, these huge swaths of land enable large species like bears, alligators, and cats to roam with less interference from human development. Restoration of longleaf pine and dune ecosystems mean the land and waters are managed to ensure the survival of smaller endangered species like flatwoods salamanders, beach mice, gopher tortoises, red cockaded woodpeckers, and sea turtles. The confluence of less development (compared with densely urban areas to our south), large state and national parks, and protected military bases have allowed plants and wildlife to thrive unlike any other region.

In science, we measure both species richness (the number of different species in an area) and abundance (actual number of individuals) to come up with an index for species diversity. Generally, the higher these numbers, the healthier the ecosystem. A clear example of this can be seen when monitoring water quality in streams. If you sample the macroinvertebrate population of a creek and find only bloodworms, you know water quality conditions are terrible. These species can survive in sewage water. But, if you find dozens of species, particularly the larvae of pollution-sensitive caddisflies, mayflies, and stoneflies, this indicates the water is clean and hospitable to a wide variety of species. These insects serve as the basis of the food web for fish, crabs, and larger animals that maintain a healthy ecosystem.

It’s generally understood in ecology that the “higher the diversity, the greater the stability.” When we create monocultures—ecosystems containing one or only a handful of dominant species types—these systems are weak and susceptible to attack. Agricultural operations that grow one crop are prime examples of how monocultures can be highly vulnerable—orange groves devastated by disease or freezes; chicken farms wiped out by avian influenza. They cannot adapt to threats, and being genetically similar they can be easily devastated by a single disease or environmental threat. Having a diversity of species creates a redundant “back-up” system for crucial ecosystem services, like providing pollen, erosion management, or shade from extreme heat if other species suffer from pathogens or parasites.

Just like economists measure the health of an economy by productivity, ecologists can analyze ecosystems mathematically. And where are those most productive ecosystems located? It’s not the extreme habitats of tundra, grassland, and desert, where only a handful of species survive. The most productive ecosystems—those cycling nutrients, producing oxygen, and converting solar energy to biomass, are the most diverse ones. At the top are tropical rainforests, coral reefs, and estuarine swamps and marshes. These ecosystems have thousands of moving parts and are virtually impenetrable to a single disease or pest wiping them out. If one species suffers, there are so many backups to fill in and perform the important roles. In fact, the only disturbance any of these systems can’t defend against are complete clearing or extreme pollution by humans.

The world is much bigger than humanity. It is wise to consider the words of my favorite biologist, E.O. Wilson. An expert on insects, especially ants, he once said, “If all mankind were to disappear, the world would regenerate back to the rich state of equilibrium that existed ten thousand years ago. If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.”

13

13