Walking along the beach, my eyes are naturally drawn to the waves. That mesmerizing, repetitive motion of water is both calming and endlessly fascinating. But have you ever looked back at the dunes and noted the shape of the vegetation growing on those big mounds of sand?

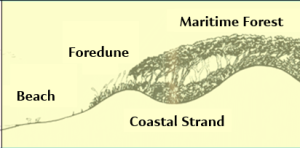

Dune plant zonation follows a predictable pattern. As you move inland beyond the open beach, you hit the front slope known as a “foredune.” This area is populated by fast-growing and early colonizing grasses and vines that help hold the shifting sand in place. The primary dune, just uphill of the foredune, includes taller grasses and shrubs. If the dune has time to mature, taller shrubs and small trees will take root. Instead of growing upright, however, these trees will grow backwards, leaning away from the water.

While the best description of that shape is probably “windswept,” it’s not only the constant sea breezes that create that curvy appearance. Compared to their inland-growing cohorts, many of the more mature plant species appear quite stunted.

So, if it’s not just the wind, what is it? It’s the salt. Specifically, wind-borne salt spray. As waves crash on the shore, salt particles in the air and beach blow inland. Once that salt hits the plants, they begin to struggle. Salt is an inherently difficult compound for living things to manage. Humans, for example, can die from drinking saltwater–the salt/freshwater osmosis imbalance in our kidneys eventually dehydrates us to the point of death. The same thing can happen with plants unless they adapt to the dry, salty environment. Constant exposure to salt in the air dries out dune plants, and its corrosive effects can expose delicate inner tissue and prevent healthy stems and leaves from forming. To protect itself, a plant will focus energy towards branches and leaves in the opposing direction from the shoreline, so new growth is protected. Over time, the plants grow in an arc away from the saltwater. This growth pattern is known as salt pruning, and its effects can be seen in both marine and brackish environments.

The best examples of salt pruning in our area are typically seen in sand live oaks (Quercus geminata). On Pensacola Beach, the sand live oaks atop the dunes grow low, bending backwards away from the water. They form a stubby thicket well into the roadway. But, once you reach the backside of the dune the tree shape changes. While still gnarly and lower growing, these oaks are protected from the salt spray and can grow branches upright and horizontally instead of at a 45° away from the Gulf. These trees have other adaptations to living on the coast, like their leathery, cupped leaves that hold in water and ward off the salt. Species growing in salt marshes and coastal areas (halophytes) have also evolved numerous strategies to keep salt out or move it away quickly. If you live on a brackish or marine waterway, it’s important to use salt-tolerant plants in your landscape.

Salt does have provide some benefits to the young maritime forest. The sandy soil is nearly devoid of water and nutrients, so the steady spray provides minerals and organic matter into the dunes to help nourish the tough plants that do manage to grow there.

7

7