I’m not sure if you’ve ever stared at a plant for 15 minutes and tried to count and identify all the insects on it, but I can attest it’s not easy! That is exactly what I, and dozens of volunteers, did last Friday (August 23) as part of the Great Southeast Pollinator Census.

I’m not sure if you’ve ever stared at a plant for 15 minutes and tried to count and identify all the insects on it, but I can attest it’s not easy! That is exactly what I, and dozens of volunteers, did last Friday (August 23) as part of the Great Southeast Pollinator Census.

Started in Georgia in 2019, the idea of the census is to capture a snapshot of data to use as a baseline to understand how our pollinator populations are doing. The data can demonstrate any major changes or trends, like an increase or decrease in insect types or overall numbers from year to year. The census creators also hoped used the effort to teach the public about the importance of insects and increase their habitat. This year is the first time Florida joined the effort. Each year, the number of participants in the count has risen, with over 700,000 insects counted last year. Since the project’s inception, 2,500 new pollinator gardens have been planted because of the census.

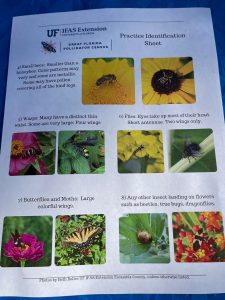

The process is simple. Participating observers take a few minutes to look over some identification charts, and are given a checklist that includes photos of the target insect types. Once the 15-minute clock starts, you just watch a section of flowers or a shrub and record how many insects land on the plant. Identification was kept at a basic level, starting with the largest carpenter bees with “shiny hineys” and bumblebees with “fuzzy rears.” Along with these were honeybees, smaller bees, wasps, flies, and butterflies/moths. On my particular observation shrub, a yellow buttercup bush (Turnera spp.), the carpenter bees reigned supreme. They could fit their entire chunky bodies inside the flower and dig in. After those, I counted dozens of small flies. They moved so quickly that I likely missed as many as I tallied, but they were definitely huge fans of the plant.

When we think of pollinators, bees and butterflies are the first to come to mind for most of us. But we forget the underdogs (underbugs?); the less showy and more creepy critters, like flies and wasps. Pollinator wasps and flies very rarely sting, and are often quite shiny and colorful. They do a lot of important work for our ecosystems.

If you don’t have the space, time, or energy to plant a pollinator garden, you can also build or purchase a “pollinator hotel” for these insects. The structures consist of numerous round tubes of different diameters—often made of cut bamboo—attached together, which allow insects of varying sizes to inhabit the houses.

8

8