I am sure everyone has noticed how cold this winter has been. We have had multiple days in the 20’s here in the Florida panhandle, even some snow flurries near Pensacola. I was first told this may happen by a Sea Grant colleague of mine who works with oyster farmers. Six months ago, he said the Farmer’s Almanac mentioned this would be a colder than normal winter. A few weeks later a Master Naturalist mentioned that if it was heavy “mast season” (lots of acorns on the ground) it would be a colder winter. We certainly had a heavy mast season in Pensacola this year, acorns were EVERYWHERE. And here we are. As I type this it is 27°F outside.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

This past week I was at a Sea Grant meeting. We were discussing this cold and another colleague mentioned that it was an El Nino year. That’s right… it is an El Nino year, and many know that the weather does change when this occurs.

I first heard of the El Nino shortly after receiving my bachelor’s degree. I was teaching at Dauphin Island Sea Lab, and we had a video series on oceanography and one episode discussed it. It explained that commercial fishermen in Peru were the first to notice it over a century ago.

Off Peru’s coast is a large ocean current that originates in the Antarctic, flows north towards the equator passing the west coast of South America along the way. The water is cold and full of life. The Andes Mountains also run north-south along the coast. Cold air at the top of the mountains runs down towards the coast and offshore. As it blows offshore, it “pushes” the surface water of the ocean offshore as well. This generates an upwelling current moving from the ocean floor towards the surface, bringing with it nutrients from the sediments below. This nutrient reach seawater, mixing with the highly oxygenated cold water, and the sun at the surface creates the perfect environment for a plankton bloom, and a large bloom she is. This large bloom attracts many plankton feeding organisms, including the commercially sought after anchovies and sardines. This in turn supports the tuna fishery that comes to feed on the small fish. These are some of the most productive fisheries on the planet.

Based on records kept by Peruvian fishermen, every three to seven years the surface waters would warm, and the fish would go away. It was lean times for them. When it did occur, it would do so around Christmas time. So, the fishermen referred to it as the El Nino – “the child”.

Based on the video episode we showed the students, others began to notice warming along the western Pacific and realized it was a not a local event, but a global one. A high school friend of mine does sound for nature films and one of his first projects was to video the effects of the El Nino on the seal nesting season in California. As in Peru, the cold waters become warm, the bloom slows and the fish go away, with less fish the mother seals have no food so, cannot produce milk for their newborns waiting on the beach. As horrible as it sounds, and was to watch in Mike’s film, the mothers eventually abandon the newborns to starve.

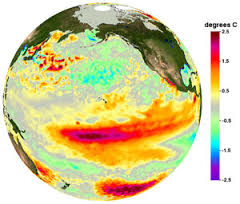

The video we showed at Sea Lab followed marine biologists studying corals along the western coast of Central America. Here the waters were warming as well, warmer than normal, and the corals were stressed and dying. With orbiting satellites now in place oceanographers were able to view this event from space and watch the entire thing unfold. These images showed that during a normal year the western Pacific had cold water along California and much of South America. The waters along western Central America were warm. But during an El Nino year, warm water replaced the cold, particularly near Peru. Scientists were able to connect several events to El Nino seasons. Increases in wildfires in the western US, people were viewing the northern lights at lower latitudes, droughts occurred where it was usually wet, floods occurred where it was usually dry, and during one El Nino season the Atlanta Falcons made it to the NFL playoffs. Weird things were happening.

The obvious question for science is what drives these El Nino events?

It is understood that our weather and climate are driven by ocean currents. The “dry air” everyone talks about in the western US is driven by the cold California Current. Likewise, the “humid air” of the southeastern US is driven by the warm Gulf Stream. If you alter these currents, you alter the weather and climate of the region. How do you alter ocean currents?

Image: NOAA

In the 1980s, when I was teaching at Dauphin Island Sea Lab, the video suggested a connection to sunspots on the surface of the sun. At the time, they were not sure whether the increased sunspot activity triggered the El Nino, or whether there was something else going on, but there was a correlation between the two.

One explanation comes from a textbook on oceanography I used when I was teaching marine science during the 1990s1. It explains the event as such…

- During “normal years” cold water from the Arctic and Antarctic runs along the western coasts of North and South America – both heading towards the equator. Once there, the earth’ rotation moves this water westward towards Australia and Indonesia, warming the water as it goes.

- Apparently, the ocean currents cannot transport and disperse these warm waters effectively once they reach the western Pacific. Thus, warm water begins to build there.

- This accumulating warm water seems to reverse the trade winds that normally flow from the eastern Pacific to the western along the equator. This wind reversal occurs between November and April. It mentions that in the late 1990s the cause of this wind reversal was not well understood.

- This wind reversal is often followed by the development of twin “super typhoons” (very strong typhoons) north and south of the equator.

- The extreme warm water in the western Pacific affects the weather in the region and this “heat mass” expands spatially. During this expansion, the high-pressure system that sits over the eastern Pacific, bringing them the dry air we know California for, weakens. At the same time, the normal low-pressure system over the western Pacific weakens and, in a sense, things are flipped. This atmospheric change is called the Southern Oscillation, and the entire event was termed the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

- The power of the typhoons moves warm water from the western Pacific across the equator to the America’s. The waters there warm and the historic El Nino This movement takes several months.

- The El Nino will persist for one to two years. When the warm water eventually releases its heat, the waters cool, and normal conditions return. Until the next El Nino forms.

- In the 1990s they had already noticed an increase in the frequency of El Ninos (based on old fishermen’s logs). They suggest climate change may be driving this.

- During El Nino years weather patterns change globally, as mentioned above. This altering of the weather impacts all sorts of biological processes, as mentioned above.

- Often, the “return” of colder water along the western Pacific “overshoots” normal temperatures and the ocean becomes colder than normal. This has been termed the La Nina.

I kind of imagine the whole process like a sloshing pool of water flowing towards one end of the pool, bouncing off and sloshing back to the other. But instead of water “sloshing around” it is temperatures.

But this was 1996. Have scientists learned anymore about this event?

Not much has changed in their explanation, other than we are much better at predicting when they will happen and alert the public so that farmers, fishermen, fire fighters, etc. are prepared. They do seem to be increasing in frequency.

For the 2024 El Nino, which NOAA began alerting the public in the summer of 2023, they are predicting it to continue for several seasons2. There is no doubt that this winter is colder than normal. The Florida panhandle also experienced a drought this past fall. But… during most El Nino years, hurricanes are few in the Gulf of Mexico. We will see, and watch, how the rest of the year rolls out.

Reference

1 Gross, M.G., Gross, E. 1996. Oceanography; A View of Earth. 7th edition. Prentice Hall. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. Pp 472.

2 El Nino / Southern Oscillation (ENSO) Diagnostic Discussion. Jan 11, 2024. National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association.

https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/enso_advisory/ensodisc.shtml.

3

3