Everyone has noticed the intense weather that crossed the United States in recent years. Tornadoes are hitting communities throughout the Midwest, but are also hitting places like Seattle, southern California, and even recently Pensacola Beach. Thunderstorms, though common, are occurring in waves. Typical summer days here in the panhandle include afternoon thunderstorms, but recently there have been daily squall lines beginning as early as 9:00am. I was recently camping out west and we encountered three hailstorms. Though these do occur out there, they were becoming a common thing and were also encountered in multiple states. And of course, there are hurricanes. Some are more intense and increase intensity as they come ashore, instead of decreasing as has been the rule over the decades.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Many have pointed the finger at climate change as being part of the reason why these intense weather events are increasing, and climatologists have said for decades this could happen. To better understand what is driving these storms, I decided to grab one of my old college textbooks from the shelf and read what actually forms and fuels these weather events. The Nature of Violent Storms was published in 1961, and reprinted in 1981, by Dr. Louis Battan. Though many things that were unclear at the time of the writing have been discovered, the mechanisms that generate and fuel these storms were understood.

The mechanism that begins storms is convection cells within the air rising from the earth’s surface. The air moving over warm land or water warms as well and begins to rise. The rising air lowers the air pressure at the surface and is called a low pressure system. We associate low pressure systems with storms. These storms form due to unstable air masses in this rising column of air. The greater the temperature difference between the warmer air near the ground, and the cooler air in the upper atmosphere, the more unstable the air becomes and the faster the column of air rises. As the air rises it begins to cool, become denser, and falls back to earth like a water fountain shooting water into the air. This is the convection cell we have heard about.

However, if the air mass holds a lot of moisture (humidity) the release of heat from this humid air mass rising in the column can warm the environmental air mass surrounding it enough to cause the rising air mass to continue higher into the atmosphere increasing its speed while doing so. We can see this as cumulus clouds building over the landscape and, if humid enough, you can literally watch the thunderhead build. If supplied with enough water vapor and heat, these thunderheads will grow all the way to the tropopause (the lower layer of the stratosphere where the atmosphere itself begins to warm, not cool) and form the “anvil” shape of a thunderhead we are all familiar with. As a college student taking coastal climatology (the class this book was associated with) we would sit outside of Dauphin Island Sea Lab at mid-afternoon and bet on which thunderhead would reach the tropopause first.

The upper layer of the lower atmosphere is quite cold. Here the releasing water vapor condenses into rain droplets, ice, and often hail. They fall back towards earth. Much of the ice and hail melt before reaching us but under intense conditions this frozen precipitation can reach the earth’s surface as hailstones, some being as large as three inches across. One storm we encountered in Colorado this year had hailstones about the size of a large marble. We heard that at a nearby amphitheater the hail reached the size of golf balls and many who were there to see a concert (and there was no cover to hide) were taken to the hospital.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

The one common denominator in the formation of such storms is the presence of a warm landmass or water body. The warmer these land masses and water bodies are, the more energy there is for the enhanced convection and severe storm formation. And these land masses, and water bodies are getting warmer.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

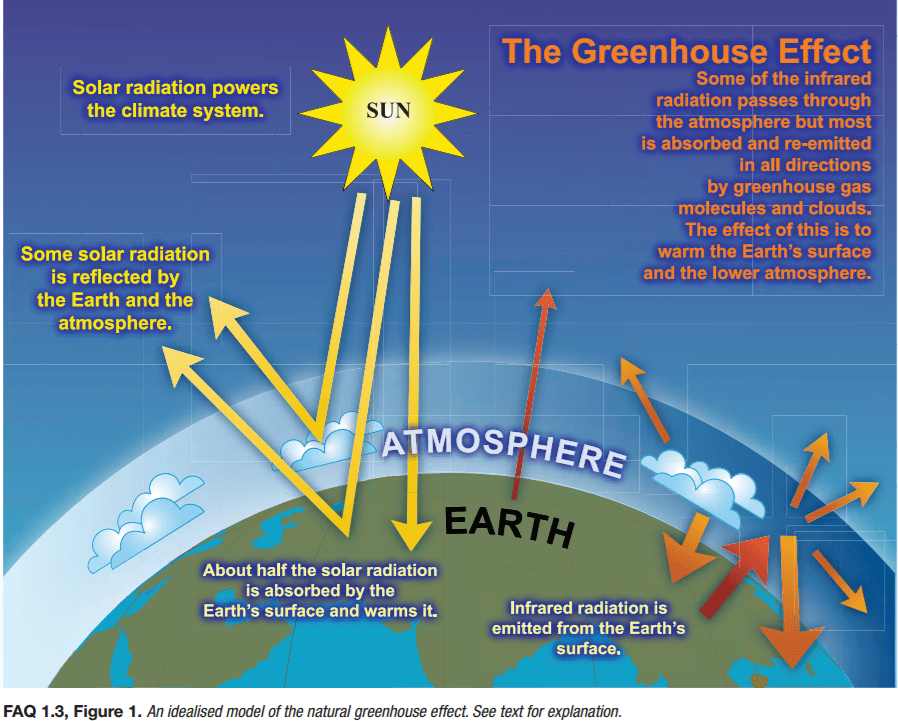

What has changed is the atmosphere itself. There are gases within the atmosphere that allow solar rays to pass through reaching the surface of the earth, but do not allow the warmed air caused by the warming of land and sea from this solar radiation to escape back into space – the so called “greenhouse effect”. This is actually good; it keeps our planet at a warmer temperature than it would be if these gases were not present and allows life to exist here. However, an increase in these “greenhouse gases” can increase the overall temperature and create problems – intense storms being one of them. The surface of the planet Venus is around 900°F. Even though the planet Mercury is closer, Venus is warmer due to the heavy amount of greenhouse gases in its atmosphere. At temperatures like this, it is understandable that life does not exist there, and scientists do not believe it could. Getting scientific instruments to the surface of Venus is difficult due to the large amount of sulfuric acid in the clouds, much of this coming from intense volcanic activity there.

Image: NOAA

On Earth, our temperatures are climbing – slowly, but climbing. As the atmosphere warms due to the greenhouse effect, it increases the temperature of the land mass and water bodies. Increased temperatures in Pensacola Bay have triggered some die offs of oysters, and the warming Mobile Bay has increased the number of jubilee’s occurring there. Remember, high water temperatures mean low dissolved oxygen levels. Increased surface temperatures will create more unstable air masses and a breeding ground for the formation of vortices that can, and do, lead to more intense thunderstorms and tornadoes. Surface temperatures are increasing in locations where historically such weather events have not been common, like Seattle. Recently, I had to make a trip to a department store at one of our local malls. Leaving the house, as I crossed our wooden deck and walked through the yard to the truck, it was definitely warm – it was July. However, when I arrived at the store, where all was concrete and asphalt, the temperature difference was striking. It was MUCH warmer. Actually, at the store front it was almost unbearable. In many of our large cities, and even in smaller ones, we have converted much of the natural landscape to concrete and asphalt, which is increasing the surface temperatures even more, and enhancing unstable air even more. We have all heard that large cities create their own weather, and it is true.

So…

How do we turn this around?

I see two paths. (1) Reduce the source of the heating – greenhouse gases. (2) Mitigate the impacts of the heating.

There are several sources of greenhouse gases, and these have been discussed in other articles, but certainly the use of fossil fuels is a major one and reducing our dependency on these would be a good start. But we are moving very slowly on this, the will to do it just is not strong enough.

To mitigate the impacts, we would need to re-think how we grow and develop the landscape. Even today, many of the new subdivisions I see clear all of the vegetation, place the houses close together with little or no green space, use asphalt roofs, and replace little or none of the vegetation. It seems our development plan does not have the will to make some much needed changes in planning either. There are many ways in which we can develop our landscape to help mitigate the warming that is occurring. Many researchers at the University of Florida have been working on this for many years. For ideas and suggestions, just contact your county extension office.

Based on the 2021 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s report, we may be past the tipping on sea level rise, but we are not on other negative impacts of climate . It is understood that with any mitigation efforts right now, there will be a lag time of several years before things begin to turn around, it is not too late. We can do this.

4

4