Each morning after my 4-8am shift I would have breakfast and then sit on the bow to look at the Deep Blue. I would scan the horizon for what was out there – may be another boat or ship – and then lean over the bow to peer into the Deep Blue. I would hang there for several minutes searching for what might pass by as the bow quietly broke through the clear cobalt blue water. And once in a while a creature would appear – only for a second or two, but I saw it. On this morning there was a large eagle ray. It was moving slowly until it felt the presence of the ship and then would zip off into the deep.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Oceanographers go to sea for many reasons but observing marine life was popular for everyone. More students enter oceanographer for marine biology than any other discipline in the subject. People love animals. And, as they get deeper into the subject of marine biology, find other amazing creatures that exist out here to which they turn the direction of their research.

Roaming through the Deep Blue, life does not seem very abundant. There are miles and miles of clear blue water with little in it. Occasionally you will see a fish, a shark, or a ray, but then nothing for minutes or hours. On land life is all around us. Trees, insects, birds, can be found without walking at all – just stand and look you will find them. Our basic understanding of the food chain works on a basic principle. Plants use solar energy to create sugars. They consume these sugars as their source of food. Animals who can consume plants do so to rob the plants of their sugars. Carnivores feed on the herbivores and so on. But it begins with plants and sunlight.

In the Deep Blue, there is plenty of sunlight, but you see no plants out there. That is… what we think of as plants. There actually are. They are small, microscopic plants called phytoplankton drifting in the water. Diatoms and dinoflagellates make up most of them, but there are many other varieties as well. But the abundance is still low. When these phytoplankton are in high abundance the color of the water is tinted green – or brown, or red.

Photo: University of New Hampshire

But out here it is clear and blue – low abundance. The missing piece to higher abundance? – nutrients. We know at home that for plants to grow they need sunlight, water, and some form of fertilizer (nutrients). They same is true in the ocean – and the Deep Blue has few nutrients. One source of oceanic nutrients are the rivers from the estuaries. These systems have plenty of nutrients and where they spill into the sea, you can see water that is not cobalt blue but greens, browns, and reds – full of phytoplankton and a higher abundance of marine life.

In the Gulf of Mexico there is a large plume of nutrient rich water where the Mississippi River discharges into the Gulf. They call this the plume, and it can be seen from space. There is a large expanse of dark river water spreading across the surface of the more dense seawater and where the dark water meets the clear blue water marine life is very abundant. Billfishermen know this. This is where you catch the trophy big blue marlin. Marine biologists have seen large congregations of sperm whale (the largest carnivorous whale) near this plume. All are feeding on the abundance found here. There are places where the geography of the land and the direction of the ocean currents generate winds that move landward. Water moving towards land can generate currents coming from the ocean floor called upwellings that bring nutrients from the seafloor to the surface. Once again, marine life is abundant, fishing is good. As the major rivers discharge into the sea they will form eddies, pockets of counter-rotating water that “break off” the main flow rotating like tornados and moving across the ocean. Many of these eddies trap layers of nutrients and become an oasis of food for marine animals.

But these marine animals we speak of do not – cannot – eat the phytoplankton – they are too small. To complete the food chain small, microscopic animals called zooplankton feed on the phytoplankton. Some forms of zooplankton are large enough to see in your specimen dish. Some appear as dark moving dots in the water sample – but under the microscope look more like cockroaches – these are the copepods – a type of crustacean distantly related to shrimps and crabs, and the most abundant form of zooplankton in the ocean. Some scientists have stated that ALL marine life, directly or indirectly, depend on these small crustaceans for their existence. There are literally 1000s of different kinds of zooplankton feeding on the phytoplankton.

Photo: Texas Tech University

During the mid-20th century marine biologist indirectly came across an amazing layer of zooplankton in the ocean. It was at the end of World War I and during World War II they discovered this layer. SONAR had been developed to detect the German U-boats (submarines). Sound was produced and echoed off of large objects beneath the sea detecting the location of the U-boats. At this point the warships would drop what were called depth-charges. These would explode when the pressure under the sea was high enough to implode the canister detonating the explosive. The shock wave would crack/destroy the U-boat and the warship would know when they hit their target by the oil/gasoline sheen at the surface. There were many times when they would drop these depth charges and no oil sheen was found – they missed. But there were times when repeated drops did not yield a sheen – yet, the SONAR was detecting a large mass below the surface. It was eventually determined that this large mass was not a U-boat but a large layer of zooplankton called the deep scattering layer. The Germans too discovered this layer and used it for their advantage. U-boats launched from Italy would have to enter the Atlantic Ocean from the Mediterranean Sea through the Straits of Gibraltar. This strait was narrow and the allies would sit listening for the U-boats – U-boats used diesel engines and you could hear them. The Germans would find the deep scattering layer, go beneath it, turn off their engines, and drift out of the Mediterranean on the out going tide. The allies had learned how to tell the deep scattering layer from U-boat and were fooled thinking what was passing was only zooplankton.

During the war, and afterwards, there was a lot of research on this layer. They found it moves up and down in the water column each day. During the daylight hours the DSL would sink into the depths – 100s of feet down. At night it would rise to the surface. As DSL moved, so did the marine organisms that feed on it, and the organisms that feed on those. It is near the surface at night and this is when most of the sightings of the giant squid occur.

As just mentioned, there are all sorts of small baitfish that travel in huge schools that feed on these zooplankton. Some of them are commercially important. Larger carnivores and oceanic seabirds follow the baitfish. Some of the large baleen whales feed on both the zooplankton and baitfish. All of this attracts the larger predators – sperm whale, orcas, oceanic sharks, etc.

Where the nutrients are the phytoplankton are. Where the phytoplankton are the zooplankton are. Where the zooplankton are the baitfish are. Where the baitfish are the big boys are – and this happens in some areas of the Deep Blue.

Too sample the Deep Blue for plankton you would deploy a plankton net. These come in a variety of shapes and sizes but must be towed to harvest. Since the ship is moving, you must use a clinometer to know exactly what depth you are towing and marine biologists can then sample at whatever depth they wish to better understand where, and when, the plankton are found.

Photo: NOAA

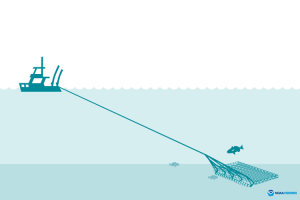

For baitfish, and smaller predatory fish, you would drag a trawl. This is a large net you would call a “shrimp net”. More often than not, they are dragged on the seafloor but they do not have to be. Researchers do not always use these – but commercial fishermen seeking this size fish will use a purse seine. Once a large school of fish is seen, they will lower a boat into the water that will drag a large net around the school and then drop a large weight called a “Tommy”. This Tommy will drop closing the net like zipping a purse closed – hence the nets name. This is hauled on board. Often fishermen seeking the larger fish feeding on the baitfish will use this method as well – such as tuna. Anything captured in a net that is not the target (what you plan to sell) is called by-catch and this is a problem – a waste of a marine resource. It was actually the focus of the study I was involved in for this cruise. One by-catch of purse seining for tuna are dolphins. They too seek the baitfish and are killed in the purse seines. Because of this, purse seining for tuna in U.S. waters is illegal.

Photo: NOAA

For the larger predatory fish, sharks etc., longlining is a popular method. This is a LONG line with hooks set every so many feet and held up on the surface by large round orange balls that act as buoys. Often a “chum line” is set on the longline and you wait to see what bites. This is a popular method of commercial fishing in the deep blue as well. There is also by-catch associated with longlining, leatherback turtles are sometimes hooked, and longlining is now regulated in U.S. waters. The “O 2” does conduct cruises where longline sampling is used.

Photo: NOAA

If your interest is marine mammals, you would cruise transects lines across the Gulf with a crew of co-operators who spend their four hour shifts up top with binoculars (during daylight of course). The “O 2” does conduct these cruises annually, though I have not been able to participate in one. Co-operators are taught how to identify the species by the rolls they make, how many ‘spouts” when they “blow” and the angle of that spout. All whales and dolphins seen are logged on special data sheets.

Photo: NOAA

Then there is life on the bottom.

The Deep Blue is deep – in some places over 10,000 feet deep. How do you sample in such a place? Well one method is trawling. You just need a LOT OF LINE to get the net on the bottom. On our cruise we were sampling on 100s of feet (maybe close to 1000 feet) but not 10,000s. The net hits the bottom, and you drag it for about three hours. Then it is hauled up and you know what we do. The ocean floor can be rocky and do a lot of damage to your net. If the bottom is rocky oceanographers will choose what is called a dredge. This is a rectangle-shaped metal box with a net attached dragging the bottom. The metal dredge can “plow” over the rock with little damage to the net (but significant damage to the ocean floor) and capture marine organisms living on the bottom. And… there are some strange creatures down there.

Open any book, or website, on deep sea creatures and you will see some strange, sometimes gruesome looking things. All sorts of eel looking fish, big mouths with big teeth, small eyes (if eyes at all), strange looking fins, and many are bioluminescent. There are giant isopods that look like cockroaches but are the size of footballs. Octopus and squid, all sorts of shelled creatures and strange looking crabs. A whole world we really know nothing about.

Photo: NOAA

One hundred and fifty years ago, they did not believe life could exist on the ocean floor. To have life, you need plants. Plants need sunlight. There is no sunlight here – thus, no plants. If no plants, then no animals. But, as we have discovered over the last 150 years, there is life there – and a lot of it. How? How does this system function without plants?

To better understand how that works – we need to go there – we need to dive to the ocean floor and explore the Gulf from the bottom. That will be the topic for Part 7 – Reaching the Bottom.

Sea stories…

As I mentioned I would usually visit the bow of the “O 2” after breakfast and dinner when my shift ended. At night it was amazing out there. Dark skies… darker than any sky you can imagine. Finding the Big Dipper and Orion was much harder because it was engulfed with all of the other stars we never see near our bright lit cities. You can gaze at the stars, see satellites going by, and – often – shooting stars as they streak across the heavens.

One evening while I was walking out towards the bow I got slapped in the face by something. It was about the size of a pencil but I had no idea what it was. Then another, then another – “what the heck?” Turning a light towards the deck I found flying fish! As the ships bow pushed the water forward these small members of the ocean baitfish world would escape trouble by swimming very fast at the surface and, eventually, extending their unusually long pectoral fins out like wings. This allowed them to glide above the surface of the ocean and avoid the larger predators coming after them. I knew this happened but was AMAZED they could get high enough to reach the deck of the “O 2”. As I walked closer to the bow the flyfish assault continued. As I leaned over the bow (shielding my face) I could see they were zipping from the surface and – I guess – being forced upward by the wind coming off the vessel. They were landing on the deck. I had read this happened to sailing ships during the times of old. I was pretty wild.

2

2