Part of the 2019 UF IFAS social media survey across Florida found that many Floridians understood how septic systems worked, but fewer understood how sewer systems functioned. This article is going to try and tell you the basics of how sewage treatment works.

As we just mentioned, many people have no idea where their sewage goes after they flush – nor do they care – as long as it does not stay here 😊. When we flush – it goes – and that is all we think about. This is one of the advantages of sewer over septic – you do not have to maintain anything. You just flush and go. However, we will see in Part 4 that there are some things that are still on us to help keep sanitary sewage from reaching our coastal waterways.

So – where does the sewage go when we are on a sewer system?

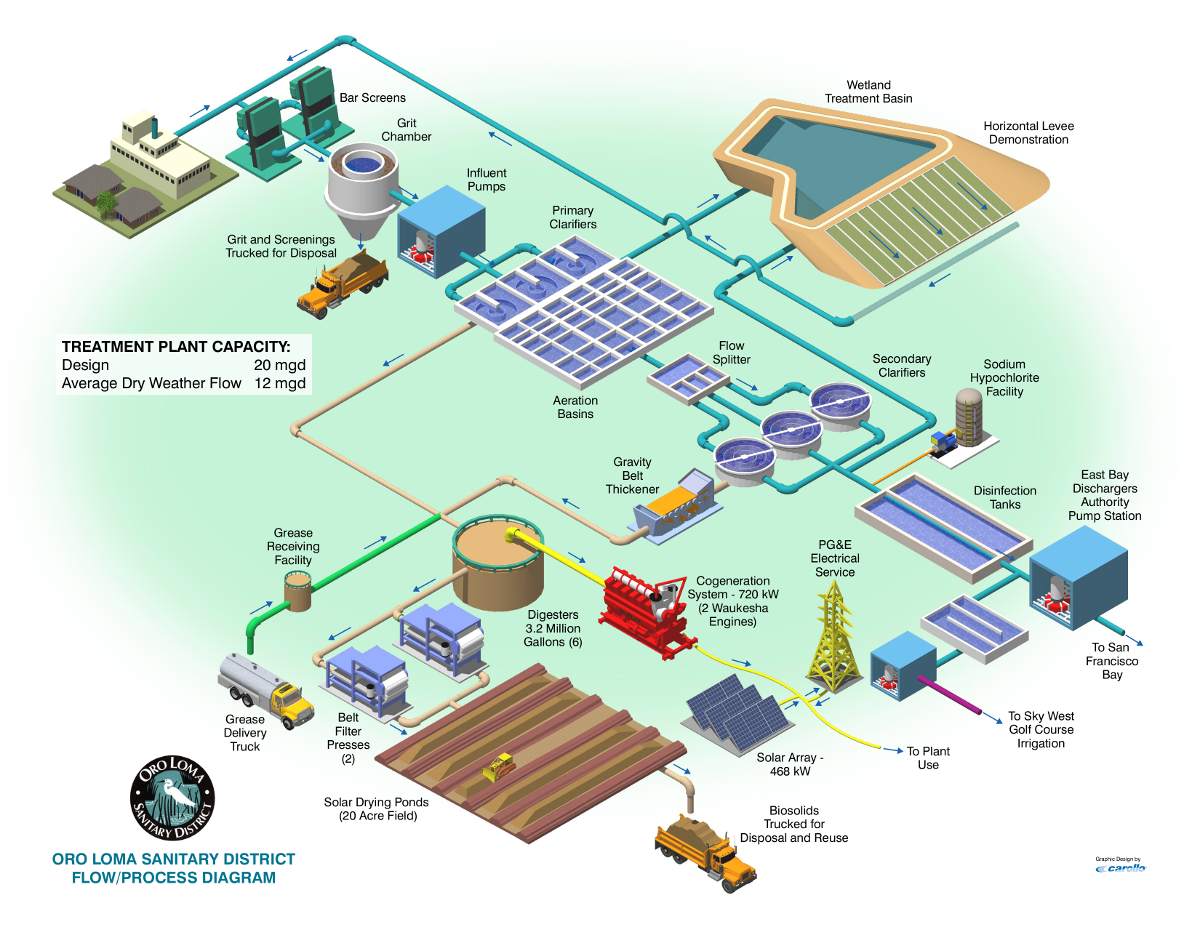

The raw sewage leaves our house through a pipe called the lateral. This line connects to the municipal sewage line under the street. From here it flows to the local sewage treatment facility. In some communities, this is downhill from the residential area, and the sewage flows via gravity. In others, it is uphill and must use a series of pumps, or lift stations, to get the raw sewage to the treatment plant.

Image: Oro Loma Sanitary District

Once it reaches the plant the sewage undergoes PRIMARY TREATMENT. This is a series of methods that physically treats the waste. Often, stop #1 is a screen that removes large objects. You would be surprised what ends up in the sewer lines heading to the treatment facility. Wood, boxes, and plastic bags. I heard one treatment plant found a small hog in their screen system.

Once past the screens the wastewater is run through a grit chamber. This continues the physical process of removing large objects from the wastewater as it trickles through. Material such as sand and rock settles to the bottom of the chamber. This settled material can be removed, treated, and disposed of.

The effluent (water) continues on to stop #3 – the settling tank. Here it is allowed to sit so that smaller fine solids can settle to the bottom of the tank – not that different if you placed muddy water into a clear 1-gallon jar and allowed it sit, the mud would slowly settle to the bottom making the water clearer. This settled material contains much of the solid waste from when we went to the restroom. Here it is called sludge. The sludge is drained off, treated, and usually dried in a pile that would resemble dirt. Some communities load this into trucks and take it to a designated area in the landfill. Some communities will use it as a fertilizer on crops. Some countries allow this but not for crops that will be used as food. I heard some locations around the world use the dried material to form bricks and building materials.

Studies show that primary treatment can remove as much as 60% of the suspended solids and 30-40% of the organic waste that is oxygen-demanding in an aquatic system.

But…

It does not remove pathogens that maybe be in the sewage, phosphates and nitrates that can cause eutrophication, salts which alter the salinity and living conditions for aquatic life, radioisotopes, nor pesticides. For this, we will need secondary treatment.

The clearer effluent remaining after settling moves to SECONDARY TREATMENT. Where primary treatment was a physical method of treating wastewater, secondary treatment is a biological method. Stop #1 is the aeration tank. Here the effluent is aerated using a sprinkler system that provides oxygen so that the microbes living in the tank can further break down any pathogens and other biological demanding waste. This treated water is then sent to a second settling tank where more sludge is allowed to settle. The settled sludge is then cycled back into the aeration tank – and the process continues. The clearer water at the surface of the second settling tank is then sent to a tank where is disinfected – often with chlorine. If balanced correctly, the amount of chlorine added is enough to kill much of the remaining bacteria but not high enough to be a threat to the environment. This water is then analyzed for contaminants, including fecal bacteria, and – if it passes the test – is discharged into a local waterway as treated sewage. Studies have found that a combination of primary and secondary treatment can remove 95-97% of the suspended solids and oxygen-demanding waste, 70% of most toxic metal compounds, 70% of the phosphorus, and 50% of the nitrogen.

For many communities this is good and is the end of the line. For others, they are willing to spend additional dollars and move to more advanced treatments before discharge – what is called TERTIARY TREATMENT. One method of tertiary treatment is using a series of filters that can reduce the levels of phosphates and nitrates remaining in the effluent. These compounds are the ones that trigger eutrophication and algal blooms and many communities feel the extra charge on their bill is worth it. These filters can actually remove some viruses. Some use chlorine for a second round, however studies have shown that increased amounts of chlorine can react with organic materials to form chlorinated hydrocarbons – which have been linked to cancers, miscarriages, and damage to human nervous, immune, and endocrine systems. For those going this route, many have opted for UV radiation or ozone treatment in lieu of more chlorine.

After either secondary or tertiary treatment, many municipalities run their treated effluent through a marsh or swamp before it reaches the open water systems. Studies have shown that these plants are very good at up taking nutrients, and some other contaminants, as the water flows through them.

Many feel this is a better method of treating human waste than a septic system. One point is that YOU do not have to manage your tank – the city does. Though this is true there is a monthly bill to pay for this service and some would rather not pay that. It is also important to understand that you are not quite off the hook yet. There is maintenance needed to the sewer system BY THE HOMEOWNER, and we will discuss this in Part 4.

0

0