The Big Easy. The Crescent City. The northernmost city in the Caribbean—no matter the nickname, New Orleans holds a storied place in our nation’s history. But without the Mississippi River, the city probably wouldn’t exist. Built strategically on the banks of the most commercially important river in the country, New Orleans’ role as a port town plays heavily into its cultural significance. Both people and products have moved in and out of the region through this waterway, whether it’s moving jazz upriver to St. Louis or exporting midwestern grain to the rest of the world.

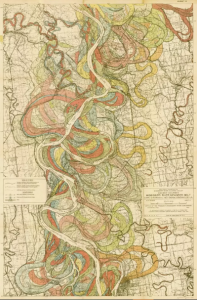

If the river were allowed to flow naturally where she wanted, however, it would most likely be located many miles west of New Orleans, through the Atchafalaya Basin. Over the years, the Mississippi has moved hundreds of times, as rivers do, based on rainfall, flow volume, and sediment movement. A famous map drawn in 1944 by cartographer Harold Fisk shows a dizzying array of pathways the river has taken over its history. However, the Mississippi River is a crucial economic engine. The shipping industry is valued at over $12 billion, and relies on the infrastructure built around the river in New Orleans. Therefore, the waterway has been locked into its current course. At the juncture with the Atchafalaya River, the “Old River Control Structure” consists of gigantic concrete towers and steel gates that keep most of the Mississippi flowing through New Orleans.

On many stretches along the Mississippi Delta, levees built adjacent to the river restrict its flow into a narrower channel, preventing it from moving or overflowing. While this artificial boundary prevents regular flooding and can protect nearby communities, there are of course environmental consequences to changing up the natural flow.

When levees restrict natural flooding, river water picks up velocity and moves more quickly downstream. This can prevent beneficial aquatic vegetation from growing and cause bank erosion, destabilizing the shorelines. That eroded sediment moves downstream and historically dropped out in the shallow waters along the Gulf, forming the basis of new marshes. But when the water and sediment are flowing faster than normal, the flow rate doesn’t allow the slow distribution of sediment and the new marshes don’t take root. The narrower channels formed by levees prevent minor flooding, often causing a worse flood downstream since water can’t slowly trickle out. Wildlife habitat is destroyed when floodplain wetlands are removed and replaced with levees, and wetlands can no longer help recharge groundwater supplies or filter pollutants through plant metabolism.

The Mississippi River drains over 40% of the United States, so any pollution within that watershed is transported downstream and down to the Gulf. A hypoxic (low oxygen) dead zone exists along a stretch of the river mouth’s entry into the Gulf because of the excess nutrients. An EPA Hypoxia Task Force has been working for many years to reduce this nutrient load by implementing projects and managing pollution throughout the states that border the river. The story of the Mississippi River is a lesson for those of us living in nearby coastal areas–a reminder that what happens anywhere in our watershed can have important consequences downstream.

4

4